Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Yomna Elsayed & Katie Davis (Part II)

/Yomna

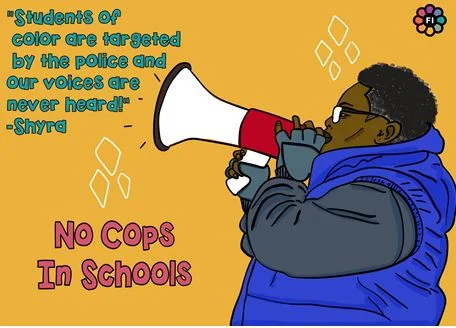

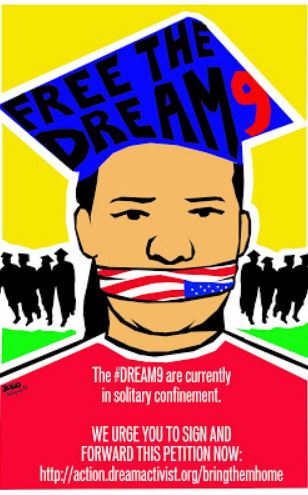

Katie, I find your work on distributed mentoring quite fascinating in not only identifying the process by which distributed mentoring takes place, but also in highlighting the value of such spaces as a means for protracted change. A persistent theme stood out to me from this conversation and the ones that preceded it, and that is the value of exploring collective spaces, previously annexed as “merely cultural” or apolitical, as instrumental to the organization of political and social movements. Practicing “real politics” has become increasingly difficult, if not due to authoritarianism or exclusionism, then due to political burnout or political polarization. In such circumstances, the existence of a seemingly non-politicized object of interest, and a space of experience can be essential in revitalizing political life in the ongoing dialog between expressive and instrumental politics.

In authoritarian settings, the cultural and artistic labels work as both a protector and facilitator: protector from political surveillance, and facilitator to all the actions that precede political action, such as subversion, identity development, and consciousness-raising. In polarized settings, spaces of art, music and humor work to build alternative bridges away from the highly contentious ones. Finding a common interest or sharing a laugh over a common fallibility all work to humanize participants and build a new community of affinity beyond the overstrained spaces of politics. In the sarcastic Facebook pages of Egyptian youth—and despite the persistent state surveillance, and political polarization— political, religious and cultural figures are consistently subverted and ridiculed, and cultural norms and traditions are often questioned amicably over a joke.

Through the trend parties, I could see many intersections with the 7 A’s of distributed mentoring, yet playfully performed. One of the main gains of the 2011 uprisings, was the Egyptian and Arab populations’ realization that they were not alone in their rejection of authoritarianism, an impression dictatorships work hard to foster among their citizens. Social media were key in connecting people previously thought isolated. Trend parties, worked the same way. They represented an aggregation of memes and parodies around a particular object or subject of ridicule. The discussion around these memes and parodies, and the comments using other memes that add to or modify the original meme, all worked to accelerate and enrich the trend with other aspects of criticism or ridicule. The product, which was sometimes saved as an album of memes and remix videos on Facebook, represented a repository, an abundance of ideas to fall back to and a shared memory of not only their playful act, but also their triumph over political and parental authority (in the form of their past and present cultural productions). While such an act may seem more entertaining than instrumental, and more ephemeral than long lasting, it nevertheless, constituted part of their collective history, that was available to draw from in their future trend parties and even comments on friends’ posts. The partying was a ‘real event’ drawing on imaginative worlds, however, ones that had real consequences on their makeup and actions as citizens. It also worked to develop affective connections between participants who bonded over an inside-joke: a common imperfection in their shared childhood experiences. This relationship is also a relationship of mutual trust, whereby all participants shared the laugh but tacitly understood that they should not over-explain it to the peering eyes of parents or authority.

Most importantly, however, were the potential of these spaces to foster critical thinking and media literacy skills. The logical loop holes and technical flaws in past media productions were a rich source for exercising these skills, all while sharing a laugh not only at the expense of these texts but at their past-gullible-selves as well. They were now able to question the decisions that went into writing and producing those texts and relate them to the wider networks of political and cultural power. Through a process of metacognition, they were able to develop new layers of engagement with the old texts they grew up with. In other words, part of their changing relationship to childhood texts was their own personal growth and their developing media literacy skills, these spaces worked to accelerate this process of maturation.

At this point, it is very hard to tell what will come out of those spaces; but, at the very least, they were a sign of life in a time of increased oppression and polarization. They represented a continuation, however playful, of Arab Spring agency, and a chance to reconnect and re-establish a common identity, one not only united by an end-goal such as that of toppling the regime, but also the self-made history, language and commitment to participatory practices. To me, this was far more valuable and long-lasting than a short-lived spectacular revolution.

Katie

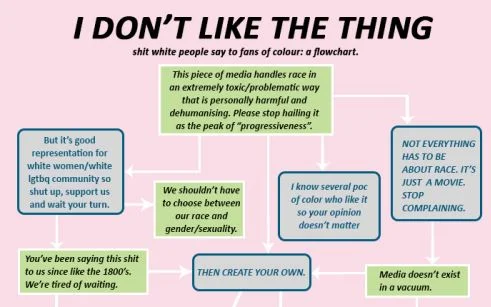

Yomna, I’m so glad that Henry paired us together! Both of our lines of research show in a powerful way the agency that young people can express in the context of their creative and playful pursuits online. And you’re absolutely right: the fact that this agency is being expressed in (seemingly) nonpolitical settings is significant. As you observe, these spaces allow for subversion, identity development, and consciousness-raising, all important to political action. As we know, cultural and artistic expressions often precede—and pave the way for—political change. We had Black presidents of the United States on television and in film before Barak Obama was elected president in 2008, as well as several female U.S. presidents before…well, hopefully we’ll get there soon! Art offers a trial ground to imagine future possibilities.

This aspect of our conversation reminds me of Andrew Slack’s concept of “imagine better.” I assume that many readers of Henry’s blog are familiar with the founder of the Harry Potter Alliance and the Imagine Better Network (and perhaps Andrew is even reading this conversation!). I love the mission statement on the Imagine Better Facebook page: “We are at the precipice of a movement where fans of all television shows, books, and movies are no longer just happy discussing those stories. People around the world are making those mythologies real and using the lessons they have learned from their favorite stories to shape the real world for real good.”

I think this statement ties in perfectly with our respective lines of research and with this discussion. Deep engagement with the various forms of artistic expression in our culture allows us to imagine new, better futures. This engagement can even provide direction for how to transform the current world into a better, more just world. I think of this connection between cultural engagement and political action as a continuum. Your work and mine seem to fall on different points along this continuum, with yours somewhat closer to political action than mine. But, they both show the possibilities associated with young people’s engagement with participatory culture to “imagine better.”

Moreover, we have each documented how personal this process can be. Whether on Fanfiction.net or through trend parties, youth come together around shared knowledge, interests, and experiences. Through the communities they form, they find support for developing and expressing their voices. Your work in particular shows how this process can serve as a very personal entry point to political engagement. At the same time, you grapple with something that Cecilia and I don’t in this regard. The flip side of the community generated from shared knowledge and interests is that it invariably leaves some people out. What are the implications of this exclusion for the political engagement that results?

I appreciate the connections that you’ve made between your work and the 7 A’s of distributed mentoring. In fact, I wish our book were not already in production; this would make a great reflection for the final chapter, where we consider where else distributed mentoring might be found beyond the fanfiction communities that were the focus of our research. I’m glad, too, that you drew connections to the skills of critical thinking and media literacy skills that young people apply as they develop new layers of engagement with the old texts they are critiquing. As with subversion, identity development, and consciousness-raising, these skills are important for political action.

The practice of “Tahfeel” is reminiscent of distributed mentoring in the way it involves people building on each other’s commentary in a cumulative fashion. It’s important that people can see each other’s expressions in a persistent way and build on those expressions publicly – a great example of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. One area of difference I noted between your work and mine relates to the tone of anti-fandom. Although we certainly documented some negative interactions on the fanfiction sites we studied, the overwhelming tone of these communities was positive and supportive. It seems you’ve documented somewhat more “biting” forms of cultural critique through the concept of anti-fandom. Yet, this cultural critique ultimately contributes to positive affect among participants, who form bonds around their shared perspectives. (But here, too, I wonder about the implications for political engagement if those who lack the necessary background knowledge are excluded from participation. Might this dynamic contribute to political polarization?)

I was particularly intrigued by the connection you drew to acceleration. You note that the trend parties from your research acted as spaces where young people’s personal growth and maturation were accelerated as they re-engaged in a critical way with the texts from their childhood. In our research, Cecilia and I had originally conceived of acceleration in the context of accelerating feedback, guidance, and mentorship around a particular fanfiction work, but it can absolutely apply more broadly to individuals’ personal growth. In fact, we do reflect in the book on how the experience of distributed mentoring contributes to young people’s growth as writers; through their development as writers, they engage in important identity development work. So, I definitely appreciate the connection you’ve made between distributed mentoring and personal growth in the context of Egyptian online trend parties. It makes me wonder: Could distributed mentoring help to accelerate the transformation of young people’s cultural engagement into political change?

__________________

Yomna Elsayed is a Lecturer of Communication at the University of Southern California online communication management program. She earned a PhD in communication from the Annenberg School for Communication at USC. Her research examines the role of popular culture and technology in advancing cultural and social change in the US and the MENA region.

Katie Davis is an Associate Professor at the University of Washington Information School, Adjunct Associate Professor in the UW College of Education, and a founding member and Co-Director of the UW Digital Youth Lab. Her research explores the role of new media technologies in young people’s personal, social, and academic lives, with a particular focus on the intersection between technology and identity development during adolescence and emerging adulthood.