More than Mere Ornament: Reclaiming 'Jane' (1 of 4) by Adam Twycross

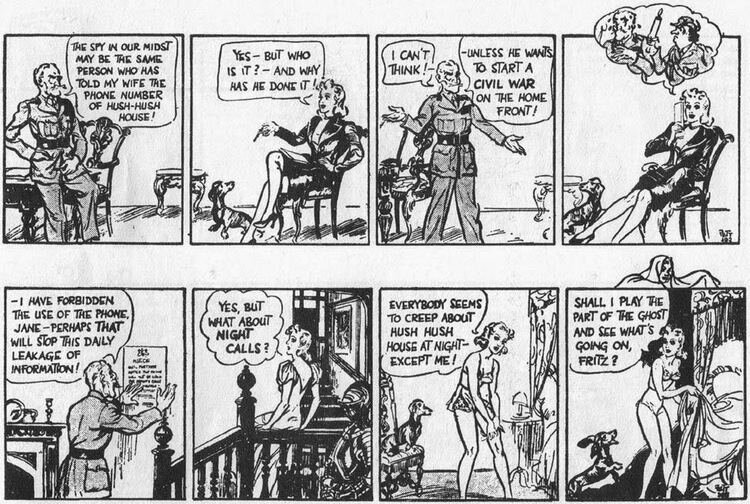

/Jane was a newspaper strip that first appeared in the Daily Mirror in December 1932. Created by Norman Pett, it was originally a daily gag strip, but was redeveloped as a continuity series in 1938. It developed an increasingly erotic edge, and became the most popular British comic strip of the Second World War (Chapman 2011, p.38), with its popularity boosted by republication in a series of forces newspapers and the arrival of spin-off publications and stage shows. In 1948 Mike Hubbard replaced Pett as principal artist, and the series continued for a further eleven years before Jane’s story finally concluded in October 1959.

In both popular and academic discourse, Jane is typically remembered in uncomplicated terms. The series is most commonly assumed to offer little more than a titillating glimpse at the erotic preoccupations of a bygone era, the original appeal of which can be credited to the lusty desires of its wartime audience. Decades after Jane’s heyday the Radio Times gave a sense of the character’s cultural positioning when it described Jane as the “scantily-clad cartoon heroine who cheered wartime Britain” (Radio Times 1982, p.1). In the same era, the Liverpool Echo recalled “Jane, of the lacy bra and snapping suspenders, the legendary strip cartoon heroine of Word War 2” (Jones 1982, p.8). More recently, from the realm of the popular historiography, authors such as Virginia Nicholson and Joshua Levine have continued to perpetuate a mythology that sees Jane’s primary function as being the facilitator of male sexual desire during the Second World War. Nicholson’s Millions Like Us describes Jane as a wartime “fantasy driven by lust and loneliness” (Nicholson 2012, p.226), whilst in The Secret History of the Blitz Levine dismisses Jane simply, and with striking inaccuracy, as “a character whose clothes fell off, in front of groups of men, for no apparent reason” (Levine 2015, loc.3063). The associative link that ties Jane so firmly to notions of erotic appeal and the gendered experience of the war are often framed within a wider wartime context, and in particular the perception that Jane’s body was used as a vehicle to both incentivise and reward male participation in the war effort. In 1994, for example, the Irish Independent published recollections of the wartime Jane, including the suggestion that

“they dropped a consignment of the papers to the troops near Caen at the Pegasus Bridge, and they made huge advances into France after that. The joke during the war was that the British Army always attacked when Jane stripped to her scanties” (Irish Independent 1994, p.4).

So ubiquitous is this vision of Jane that it persists even in academic appraisals of British comics history and in books devoted entirely to Jane itself. James Chapman, in British Comics: A Cultural History, for example, discusses Jane firmly through a wartime lens (Chapman 2011, p.38-42). He describes the series as “the most popular comic strip of the war” with an audience composed largely of “schoolboys and servicemen”, drawn in by a basic motif of a heroine routinely shedding her clothes. Andy Saunders, in Jane: A Pin-Up at War, similarly frames Jane as an icon of wartime sexual fantasy, concluding that modern sensibilities would inevitably find the series “sexist, and certainly exploitative of women” (Saunders 2004, p.16) .

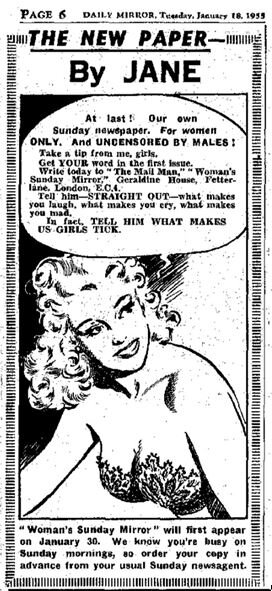

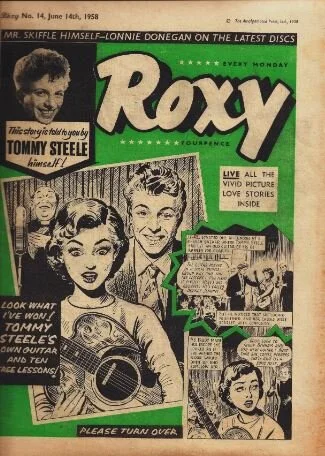

Despite the near universality of this mythology, however, there are compelling reasons to question its thoroughness, and ultimately its validity. Despite being widely assumed to have been aimed at male audiences, a more comprehensive engagement with the historical record reveals that Jane appealed as much to- indeed sometimes more to- women as it did to men. Smith (1975, p.83) notes that in the decade of Jane’s arrival, the Daily Mirror was considered to be a paper aimed primarily at women, with a readership that was around 70% female. An internal Mirror survey from 1937, meanwhile, found that of these 85% were regular readers of Jane. Despite the character’s subsequent fame as a ‘forces sweetheart’ in the war years that followed, a similar poll conducted in 1947 found that Jane’s appeal to women had remained consistent with the level recorded a decade earlier. This time the poll targeted female readers specifically, and again 85% reported that they were regular Jane readers (Cudlipp, 1953, p.75-76). The continued centrality of a female audience to Jane can be identified in other ways, too. Towards the end of the series’ life, for example, in January 1955, the Mirror Group launched a weekend companion to the Daily Mirror entitled the Women’s Sunday Mirror, and Jane was chosen to front much of the in-house publicity. The new Sunday edition was described as “the new paper by Jane”, and advertising reused images from the daily strip, with new speech balloons seeing Jane address female readers directly as she exhorted them to make contact so that the new paper could accurately reflect “what makes us girls tick!”

‘Jane,’ Daily Mirror (1955)

Similarly, although Jane is usually considered synonymously with the Second World War, in truth the series was a long-lasting one. It appeared day after day, week after week for nearly thirty years, persisting through decades of huge social and cultural change for Britain and the wider world. Around 80% of Jane’s original output occurred during peacetime, and had no appreciable connection either to the Second World War or to wartime conditions. The persistence of Jane’s cultural association with the war, however, means that huge swathes of the strips’ history have been ignored and forgotten. Yet if, as Chapman (2012, p.42) suggests, Jane offers a “good reflection of wartime changes in British society”, it seems curious that so little attempt has been made to identify similar process at work in the strips’ wider history.

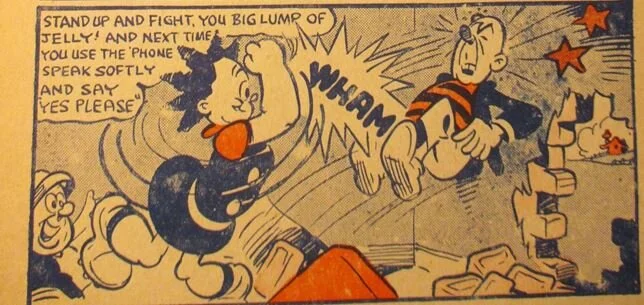

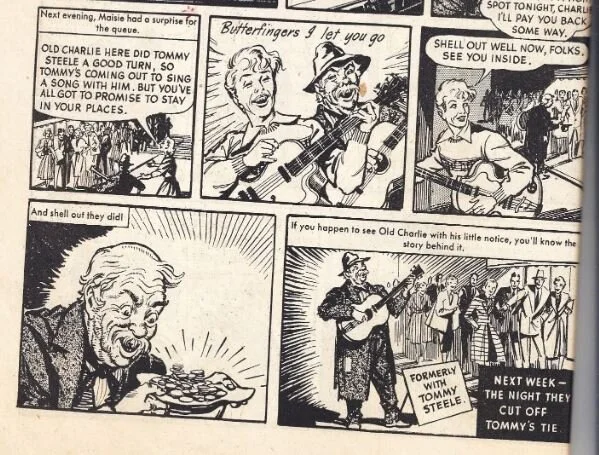

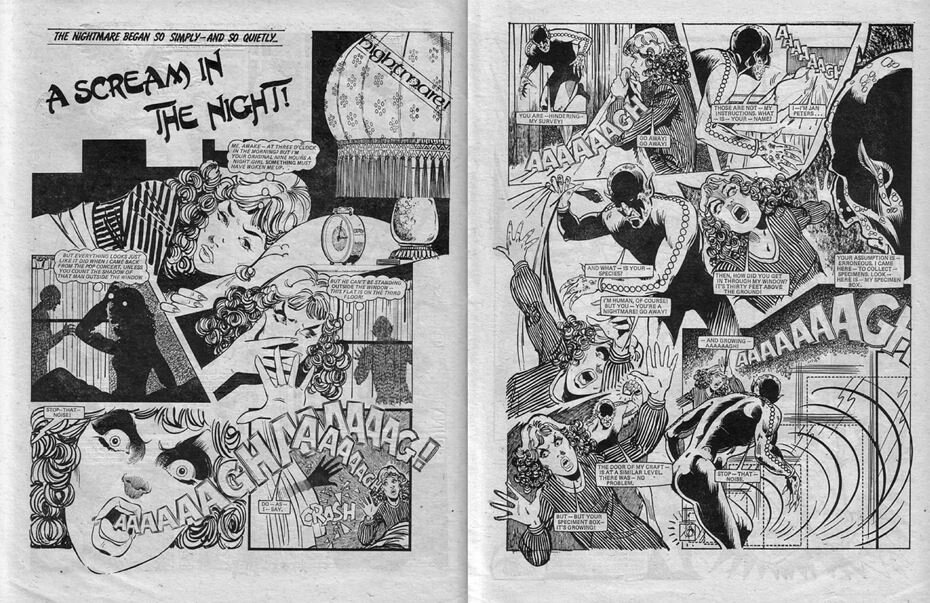

Even the oft-repeated suggestion that a clear causal link can be established between Jane’s nudity and the need to satisfy a male audience of armed forces personnel (see, for example, Andrews and McNamara 2014, p.187) does not stand up to much scrutiny. Reinforcing the conceit that Jane’s nudity was initiated as a spur to armed forces morale, it is often claimed that, after years of teasing, Jane’s first fully nude appearance occurred on or around D-Day, the 6th June 1944 (see, for example, Daily Mail 1994). Although on the day after D-Day the Daily Mirror did indeed run a strip in which Jane appeared in the nude (fig.2), this was far from a novelty. In fact, as this article will discuss in detail, such nude appearances pre-dated the war by some years, and resulted not from a desire to satisfy wartime troops, but from an unconnected revolution in the Mirror’s editorial style that occurred during the latter half of the 1930’s.

Pett and Freeman, 1944

Much of the cultural memory surrounding Jane is, therefore, erroneous, and the story of Jane’s full history is both more complex and more interesting than popular legend allows for. This essay will begin the process of fleshing out in more detail the true story of Jane’s development, focussing in particular on the way in which the series developed during its early pre-war period.

Jane’s debut, in December 1932, occurred at a time of wider turmoil for its parent publication. Established in 1903, the Daily Mirror had survived a rocky start to become, by the end of the First World War, Britain’s best-selling daily paper with sales often in excess of two million. Throughout the 1920s, however, the Mirror had struggled under a gradual but seemingly inexorable decline that had seen its readership collapse to less than 800,000 by the early 1930s (Horrie 2003, p.45). Principally, this had been the result of chronic mismanagement and interference by the paper’s principal shareholder, Lord Rothermere, who had spent years neglecting the Mirror and siphoning off its financial resources in order to bolster other parts of his sprawling publishing empire (Horrie 2003, p.35). Like many newspaper proprietors, Rothermere was also adept at meddling in his paper’s editorial direction, which in his own case was particularly unfortunate, for he was a spectacularly poor reader of the moral and political tides of the early 1930s. Under his guidance the Daily Mirror became a vocal supporter of the ‘strong leaders’ of fascist Europe in general, and of Nazism in particular, as well as of Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts and their virulently anti-Semitic campaign to establish fascism in Britain. Compounding this highly questionable editorial direction, the Mirror was widely derided as a dull and anachronistic, regarded in some quarters as

“a silly, insignificant little Tory newspaper that ran quaint front-page pictures of ‘girls in pearls’, county cricket matches and brass bands playing music to caterpillars” (Horrie 2003, p.45).

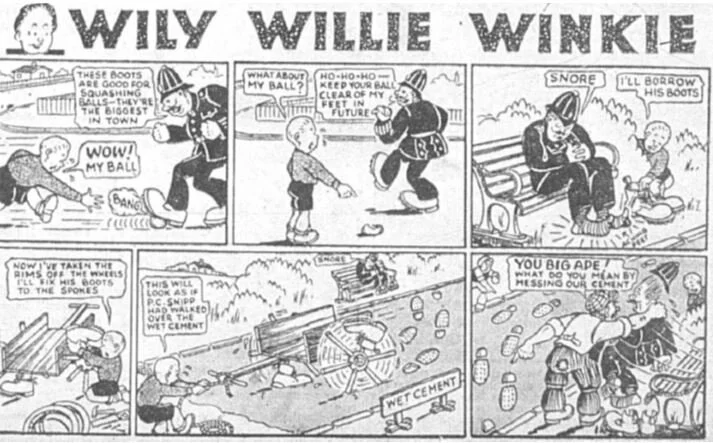

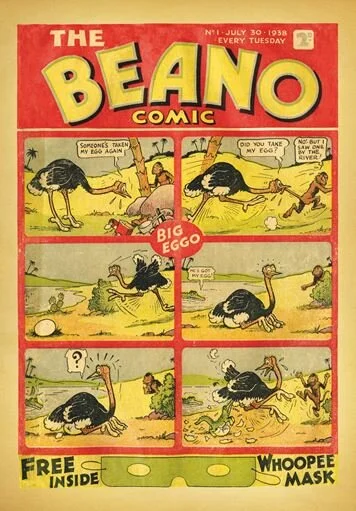

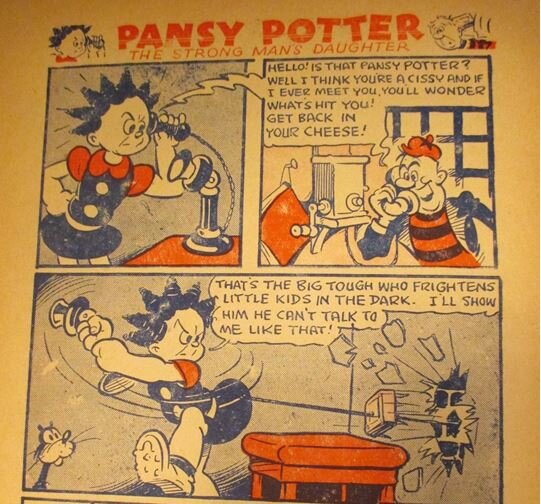

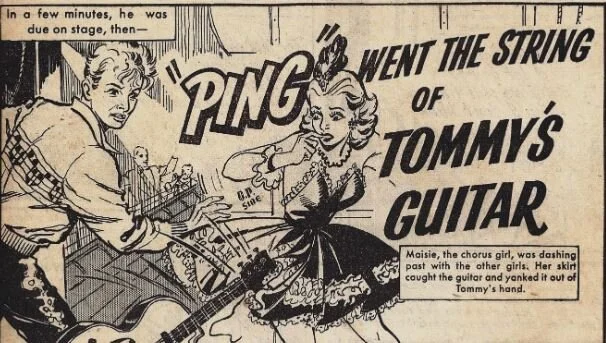

Although the Daily Mirror’s future therefore looked bleak at the time of Jane’s arrival, the paper’s salvation lay close at hand. Although not yet obvious, in less than two years the Mirror’s pictures editor, Harry Guy Bartholomew, would be promoted to editorial director and would embark on a dramatic reconceptualization that would transform the Mirror into a brash, irreverent, working class newspaper (Bingham 2011, p. 115). The huge resurgence in popularity that would follow would irrevocably break Rothermere’s control over the paper and cast the newly invigorated Daily Mirror as “the model for popular journalism throughout much of the rest of the world for the rest of the century” (Horrie 2003, p.45). Bartholomew was a bombastic figure who was, in many ways, entirely the opposite of Rothermere. Irascible, foul-mouthed, and only semi-literate, he also harboured a particular, though for the time being carefully concealed, contempt for the pomposity and entitlement of the upper classes (Conby 2017, p.127). He was also almost preternaturally gifted at understanding the needs and nuances of modern news-craft, and he had a particular awareness of the power of the image as a driver of sales. Later he would be remembered as “simply and solely a picture man, who used pictures in a way they had never been used before” (Pilger 2010, p.381), but of all the visual arts it was perhaps cartoons and comics that were closest to Bartholomew’s heart. He was a sometime cartoonist himself, and occasionally had even ghosted for W.K. Haselden, the Mirror’s principal cartoonist who had been providing a daily dose of light social satire since the paper’s earliest days (British Cartoon Archive 2016). Although in 1932 Bartholomew had yet to gain control of the Mirror, as pictures editor he was able to commission new material. His power and influence within the paper’s hierarchy was also growing, and it was Bartholomew who employed Norman Pett to create Jane. Up until this point Pett’s cartooning career had been somewhat unremarkable; although he had been a regular contributor to Punch since the end of the First World War, he still supplemented his income with part-time work at the Birmingham School of Art. He enjoyed a somewhat unconventional life, and in his native Birmingham had cultivated a free-spirited lifestyle in which, despite having been married for more than ten years, he was almost permanently surrounded by young women, ostensibly to model. Given Bartholomew’s later strategy, which would make cartoons and comics a central feature of the new-look Daily Mirror, Jane can be understood as representing a ‘trial run’ for the wider revolution that would follow in its wake. Bartholomew also appears to have been using Jane as a means of verifying whether the existing audience for comics in the Mirror could be broadened and increased. Since 1919 the paper had published a juvenile strip called Pip, Squeak and Wilfred, which through the years of Rothermere-inspired decline had proved to be a rare Mirror success. As well as being a popular feature in its own right, it had provided crucial revenue from a dizzying array of spin-off merchandise that saw the central characters appear on everything from china plates to matchboxes. When commissioning Jane, several sources suggest that Bartholomew specifically tasked Pett with the creation of a series that would repeat this success with an older audiences (see, for example, Cudlipp, 1953, p.73).

Adam Twycross is currently engaged in PhD research on the development and evolution of adult comics in Britain. Between 2012 and 2019 he was Programme Leader for the MA in 3D Computer Animation at Bournemouth University’s National Centre for Computer Animation, and has previously worked as a 3D modeller, with credits including the Xbox 360 title Disneyland Adventures and the Games Workshop graphic novel Macragge’s Honour. He is co-founder of BFX, the UK’s largest festival of animation, visual effects and games.