Return and Renewal: Star Trek: Picard (1 of 3) Djoymi Baker & Roberta Pearson

/We have another conversation for your reading pleasure, this time centered on Star Trek: Picard.. Like many Trekkies (or Trekkers, if you prefer) the return of Patrick Stewart as Jean-Luc Picard for the first time since 2002’s disastrous Nemesis created an orgy of fan-gasms across the networked world, and we’re no different here at Confessions of an Aca-Fan. But how did the series fare? Did it live up to expectations? Or did Alex Kurtzman continue to anger the hard-core fanbase as he had with the Abrams’ films and Discovery? Djoymi Baker and Roberta Pearson share their thoughts. Engage!

Djoymi Baker

Star Trek: Picard (2020-) continues the story of Jean-Luc Picard (Sir Patrick Stewart), who was first introduced in the syndicated television series Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG 1987-1994), a sequel that eclipsed the commercial and critical success of The Original Series (TOS 1966-1969).

The LA Times, writing in 1988, noted that TNG “earned the highest ratings of any weekly syndicated show in the past decade”. It went on to be the first syndicated show nominated for an Emmy for best drama. Stewart last played Picard in the commercially unsuccessful Star Trek: Nemesis (Stuart Baird 2002), and Picard picks up the character in 2399, some twenty years after the events of that feature film.

This at least avoids the “prequelitis” that plagued Star Trek: Enterprise (2001-2005) and Star Trek: Discovery (2017-), both set before the adventures of Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) and his crew depicted in TOS. Enterprise struggled to get around the weight of continuity through a Temporal Cold War, while Discovery ended season two by travelling some 900 years into the future to get away from all that baggage.

Basing a series around Picard means the programme is more securely tethered to the original (Prime) timeline, but the twenty-year gap allows both for some changes and an unknown future. In the series premiere, suitably named “Remembrance”, Picard is back on Earth, having retired to his family vineyard, Château Picard, in La Barre, France, where he lives with two Romulan refugees, and his dog, Number One (played by DeNiro, a rescue dog). We learn that Picard oversaw a plan to evacuate Romulans before their sun went supernova, but when the fleet was destroyed by an attack from artificial lifeforms, Starfleet and the Federation banned all “synths” and called off the Romulan rescue plans, leading Picard to resign in protest. The arrival of a mysterious young woman called Dahj (Isa Briones) pulls him back into a new space adventure, this time without the support of Starfleet or the Federation.

I was a Star Trek fan long before I became a Star Trek scholar, so I anticipated the return of Jean-Luc Picard like re-visiting a long-lost friend. Even in the early days of television in the 1950s, commentators recognised that viewers could develop this kind of emotional connection to a television character over time, calling it a “parasocial relationship”. Star Trek: Picard may be moving on from TNG’s retro-future, but CBS nonetheless counted on at least a portion of the audience being return viewers still heavily invested in TNG’s characters.

As one of those viewers, the prospect of returning to Picard filled me with nostalgia, but of a very specific kind that harks back to its 17th century origins combining two even older Greek words: nostos (homecoming) and algia (variously translated as longing, loss, or even pain). Svetlana Boym describes the feeling of nostalgia as a type of grieving “for the unrealized dreams of the past and visions of the future that have become obsolete”. This seems particularly apt as we return to a character who is no longer in the futuristic Star Trek of the past, but rather a new Star Trek future. From this perspective, nostalgia - so often discussed as a warm, fuzzy feeling – is fraught with the impossibility of return. As a Star Trek fan, I know it’s never going to be the same, and yet I still want it, I want the pleasure with the pain.

Returning to Picard and teaming him up with new characters was always going to be a challenge, even before they threw in an isolationist Federation. Despite the eventual success of TNG, reviews were initially pretty mixed, in part because “at first brush, the crew of the new Starship Enterprise doesn't seem as intriguingly colorful as the original bunch”, as Tom Shales put it for The Washington Post in 1987. He even calls Picard “a grim bald crank who would make a better villain”.

My point isn’t to critique Shales as such, but rather to note that changing the cast of characters within a pre-existing story is a tricky business, as is changing story world while keeping pre-existing characters.

Actor Michelle Hurd, who plays Picard’s former Starfleet colleague and new crew member Raffi Musiker, says “Patrick is so respectful of the fans, anything that doesn’t ring true to his ear we’ll literally stop, say no this isn’t right, we should do something here, the fans will know”. Inevitably, there has nonetheless been considerable debate about Star Trek: Picard’s vision of the future (more of which later), and the character of Picard more specifically, particularly in regards to the season one finale.

Roberta, did you have that same nostalgic pang? Given that you previously wrote on the development of Jean-Luc Picard in your book Star Trek and American Television with Máire Messenger Davies, what did you think about how Star Trek: Picard handled that character?

Pearson

As a viewer, I would have liked the next season of TNG but as a TV studies scholar know that this wouldn’t have been possible given the changes in both the larger society and the industry since TNG concluded in 1994. I agree about nostalgia. I remember being similarly nostalgic when TNG debuted in 1987. I had been a fan since the original series in the 1960s and had survived on reruns, the films and the various Trek books. Therefore, I was both delighted at the prospect of new Trek and worried that it wouldn’t live up to my expectations – that nothing could possibly equal TOS. Turned out I was wrong since TNG in my opinion surpasses the original. Don’t think I would say that same about Picard surpassing TNG, but they are two very different shows, one made for the requirements of TV2 and the other for the requirements of TV4 if that’s where we are now. It’s interesting that there are far more differences between TV2 and TV4 than there were between TV1 and TV2. TNG is in many ways much closer to TOS than it is to Picard.

I was tremendously excited when I heard about Picard but again anxious, in part because of Discovery about which I have mixed feelings. It was lovely to see new Trek, but I shared some of the reservations of long-term fans who thought it wasn’t ‘true’ Trek – all that violence and those very strange Klingons! It also, as has Picard, tried to cram too much plot into too few episodes and as a result could become very confusing with many plot points unresolved at the end.

Launching a new Trek show poses a dilemma for the producers. The franchise desperately needs to reinvigorate itself by casting off some of the immensely complicated backstory continuity in order to bring in a new audience. This is what the producers tried to do with Enterprise, but they found it very difficult to write a prequel to TOS, when the fans at least knew the fictional future. But the producers also have to cater for the existing fan base, because they know it’s that loyal audience that’s going to be the repeat viewers and the purchasers of ancillary products such as the novels. Therefore despite the repeated claims of casting off the backstory, Discovery and Picard have offered numerous Easter eggs that appeal to esoteric fan knowledge. This is really important for increasing fan pleasure, giving a sense of mastery, and probably doesn’t decrease the pleasure of new viewers since the Easter eggs aren’t crucial to the narrative.

Picard is the only Star Trek show that has ever been named after a character. It was almost an announcement that you had to know the backstory, you had to know this character, and as it turns out, you ideally also had to know an awful lot more. I think that was a really big gamble in terms of attracting a new audience. Yet Picard is one of the most popular characters in the Star Trek universe alongside Kirk and Spock. Leonard Nimoy has passed away, and William Shatner is difficult and getting quite old, so it made sense to go with Stewart, who is well-beloved and has had an amazing career since the end of TNG. He’s now one of Britain’s foremost classical actors. When I interviewed Stewart for the book, he said that he would never go back to being Picard because the story had ended, and he’d said everything he wanted to say about the character. Interestingly in the more recent interviews for Picard he said he was only persuaded to come back to come back to it because the character was going to change. That again immediately signalled a break with the past because that’s the only way the producers could persuade him to do the show. Stewart didn’t want to make the eighth season of TNG even if that’s what I and undoubtedly many other fans would have liked.

So, coming back to nostalgia, I think we were already prepared for that pain of returning to the old only to find it unfamiliar. The particular pain for me was in the depiction of the Picard character. Picard at the outset is a diminished man in many ways. He’s older and visibly frail, he feels that his career has failed, he’s alienated from Starfleet. In way, he’s been stripped of everything that previously defined his character – his commanding presence, his starship, his crew. But by the end he has acquired another starship and another crew and is able to declare “Engage” once more and go off in search of adventure. The whole arc of the narrative for season one is about his redemption and resurrection both figuratively and literally as he is downloaded into a synth who will hopefully last at least through the scheduled season two.

All that being said, I very much enjoyed the first two episodes which did draw on the backstory by being set in the Picard Chateau which we saw in the episode “Family” and which has featured in numerous fanfics. I liked the new characters – the Romulan housekeepers Zhaban (Jamie McShane) and Laris (Orla Brady) and his dog Number One. Stewart over the past few years has himself become a real fan of Pit Bulls so that was his choice for the show.

Baker

But they didn’t take the dog into space! There was clearly an opening there.

Pearson

I wanted Number One and the Romulans to go along with Picard.

Baker

That whole household at the Château was lovely, and – as an aside – I did like that Romulus must have been more diverse than we thought previously because there are now Irish-sounding Romulans and Australian-sounding Romulans.

Pearson

And their fashion has improved too. They’re not wearing those rather naff, padded shoulder 1980s looking uniforms.

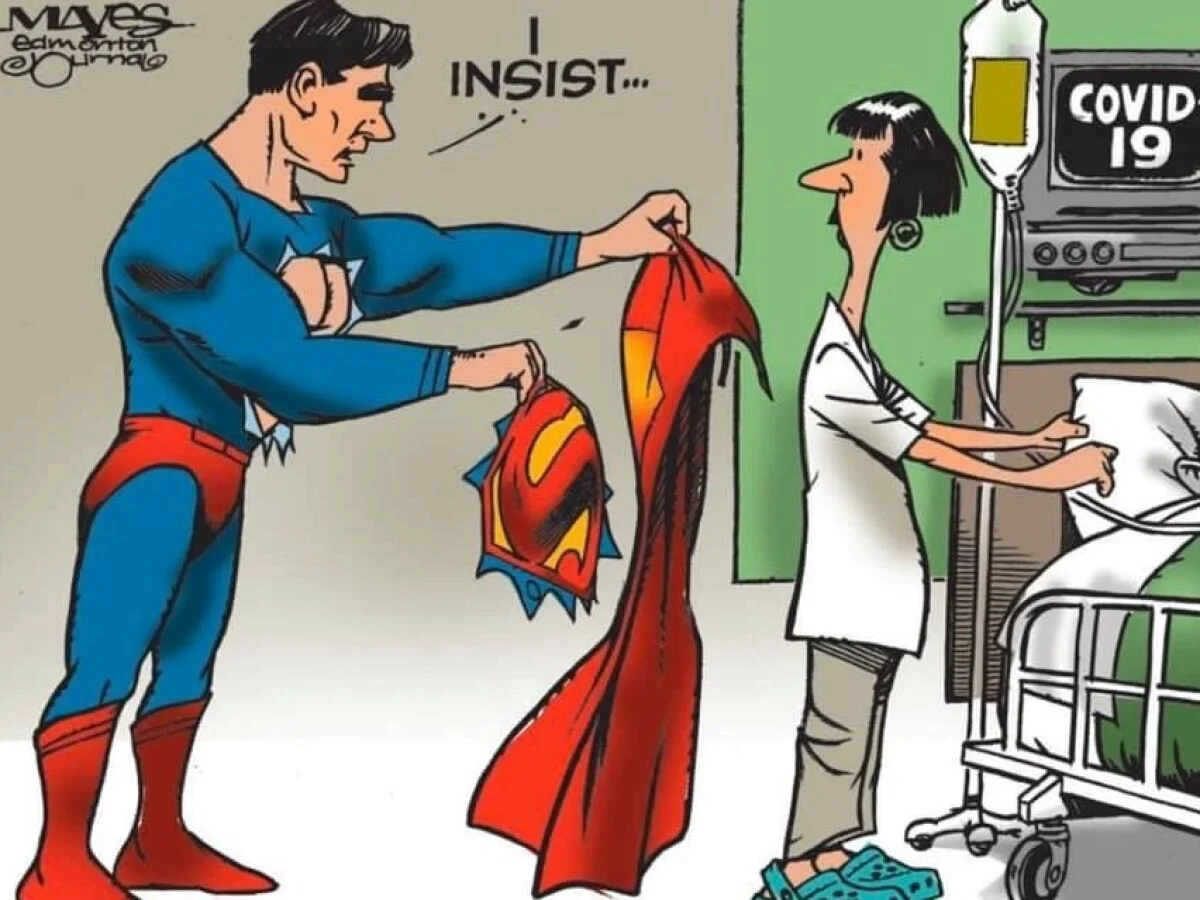

I did read some of the transmedia stories around Picard. There’s the Star Trek: Picard - Countdown prequel comic book which explains the background to the Romulan characters. Laris and Zhaban are part of the Romulan diaspora and Picard rescues them. Because they've been vintners previously – they ran their own vineyard - they bond with Picard and come back with him to the Château. Raffi also appears in the comic book, as well as the Pocket PIC novel The Last Best Hope by Una McCormack. The book fills out that character explains the backstory of Picard’s and Raffi’s relationship during the Romulan resettlement period, which the show doesn’t do very well. But I still hate the fact that she calls him JL which indicates a degree of intimacy surpassing that which he had with any TNG character.

Star Trek: Picard – Countdown, image IDW Publishing

Djoymi Baker is Lecturer in Cinema Studies at RMIT University, Australia. With a background in the television industry, she writes on topics such as streaming, genre studies, fandom, and myth in popular culture. Djoymi is the author of To Boldly Go: Marketing the Myth of Star Trek (2018) and the co-author of The Encyclopedia of Epic Films (2014). Her current research examines children’s television and intergenerational spectatorship.

Roberta Pearson is Professor of Film and Television Studies at the University of Nottingham, UK. She is the co-author of Star Trek and American Television (2014), editor of Reading Lost: Perspectives on a hit television show (2009) and the co-editor of several titles including Storytelling in the Media Convergence Age: Exploring Screen Narratives (2015), A Critical Dictionary of Film and Television Theory (2014) and Cult Television (2004).

![A road sign by the Carabineros de Chile, with their now defunct slogan "un amigo siempre" ("always your friend") [Photo credit: Benjamin Dumas, 2011].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/592880808419c27d193683ef/1585994009736-DILYPQNY9B2CC1ENZIHM/Capture.JPG)