Confronting the Challenges of a Participatory Culture (Fifteen Plus Years Later) (Part Four)

/In this final installment of our series, Henry Jenkins and Tessa Jolls offer some final reflections on Confronting the Challenge of a Participatory Culturein the current context.

Tessa Jolls: How did you react when you re-read the report?

Henry Jenkins: There are certain things I wrote that when I reread I don't remember hardly anything. This whitepaper, I reread and remembered almost every word of it. There were things that surprised me, but the conversations of that era were still so vivid in my memory. I can remember the thinking that went behind this paragraph and that paragraph, as we went to that writing process.

Tessa Jolls: Where do you see things going in terms of participatory culture? Certainly, we're at a moment right now, and you had mentioned earlier that some of the things that you had predicted, are all happening right now. It's interesting that it's taken that long to catch up, but nevertheless, it's happening. How do you see that? How do you see the moment today and where it’s going to?

Henry Jenkins: In the wake of COVID-19, we’ve seen the widespread embrace of networked technologies and particularly Zoom in response to the social isolation we're all feeling. Ironically, we were attacked as advocates of digital media for a long time because digital media was isolating us from going out into the world and engaging with the people around us. Now, we're trapped in our apartments, have no way of going out or engaging with the world, we're isolated from the people around us. I haven't seen the guy in the apartment next to mine since this thing began but we're communicating via Zoom and email on an ongoing basis. Schools have had to revert overnight to online teaching. I'm teaching online exclusively right now. We're hearing stories of kindergarteners being asked to spend three or four hours blocks online, engaging with their teachers. This conversion was done without the support that the white paper was calling for. The professional development never took place. The development of new content and techniques never took place. People do traditional teaching on Zoom and largely receive technical advice rather than pedagogical advice. So the white paper still offers tools to rethink what's going on. Of course, there are innovative teachers across America doing that thinking now. We've heard from some of them through the Civic Imagination Project. We're working regularly with some great teachers in the LA area and we do work with the National Writing Project. But teachers still need more guidance.

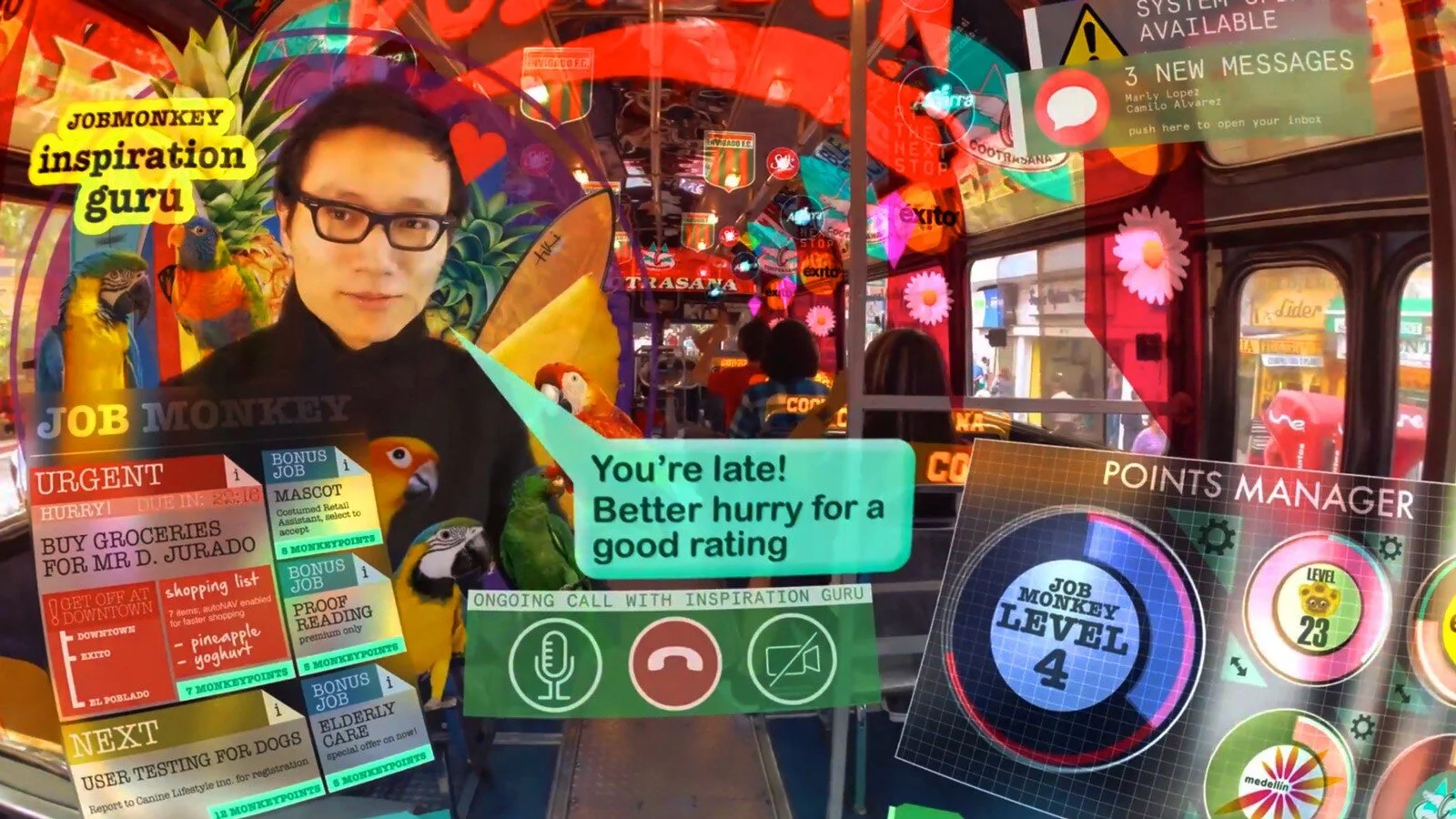

As for participatory culture, we now see it in its best and in its worse, right. We are seeing some of the challenges of networking and navigation and the verification of reliable information in a world of disinformation, misinformation, and sheer confusion. We've seen the breakdown of civility and the nastiness of cultural divides in the online world but also groups rallying to take social action in incredible ways. We've seen commercialization leaving young people particularly vulnerable to various mechanisms of data collection. Sonia Livingstone often talks about risks and benefits of children and families online and the challenge is to keep both in focus at once.

I still would remain firm in the idea that literacy in a network era is a social skill and a cultural competency; that young people need to think through together, with mentorship from adults, how to respond to the social challenges they face in this online world and that the way out of our current crisis is to foster a generation that thinks more deeply than previous generations about the human beings they're interacting with and their accountability for the information they put in the circulation. I would still like to see us raise a generation with a mouse in one hand and a book in the other.

Tessa Jolls: My take on it was that it represents the dawn of the social media era. It came out right at the beginning of Facebook. There was a reference to Myspace in it, Friendster. We've seen a lot of change in that particular environment and yet it was right on the cusp of this enormous explosion of social media. What's your take on that, Henry?

Henry Jenkins: Convergence Culture -- which I wrote just before writing this report -- makes almost no reference to social media. That's always striking to me when I look back that it's still about discussion boards and not about social media. Convergence Culturealso does not reference Web 2.0 and Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culturepicks up on both of those. So it's somewhere in that transitional period when social media is first becoming visible to us and where the concept of Web 2.0 is starting to become popular. Certainly, I was well situated to know about social media as it was coming into being: dana boyd has been an early researcher on social media, a very important figure in that space. I remembered email correspondence with her where she started describing the work she was doing on Friendster and some of the earlier social media spaces. Some of the younger graduate students on the committee were more deeply immersed in social media at that point than I would have been.

I'm proud to have an early Facebook account because of the connections between MIT and Harvard, where Facebook was first created but we weren’t using it very heavily during that period of time. When I read the stuff about Web 2.0, I cringe a little because it's still written in this moment of celebration about what a transformation in business model and orientation Web 2.0 would represent. It's not yet reflective of some of the critiques of Web 2.0 that would start to emerge in the years following that. I've become more and more clear trying to draw a distinction between participatory culture and Web 2.0 and the work we've done then.

The idealism of some of the Silicon Valley companies that I was interacting with during that period is very tangible. When I spoke to them they weren't quite in the grasp of the venture capitalists. This is something danad boyd and Mimi Ito and I talked about in our book on Participatory Culture in a Networked Era,that shifts in the way we thought about Web 2.0.

Tessa Jolls: Yes. That's why the word prescient is called for here, because the content of the report anticipated so many of the cultural aspects that would emerge with the increased use of Web 2.0 and social media. Was that your impression as well?

Henry Jenkins:Yes. I feel good about how it reads today. There's very little in it that I would change if I rewrote it now. With any of the skills we identified, you could drill as deeply as you wanted to. Many of these skills have been taken up by other specialists. Some of those skills reflect conversations that were taking place in the educational world at the time, like distributive cognition, which was something that the more education-trained members of our team brought to my attention. So, we were synthesizing what was in the air at the time. It is not that we invented collective intelligence; instead, we were consolidating it, and researchers that continue to do important work in each of those areas.

After it came out, we did some work to add one additional skill. visualization, because when we talked to science teachers and math teachers and so forth, it became abundantly clear that visualization is quite distinct from simulation. If we looked at it more closely, we might identify a couple of more skills that would need to be on that agenda. I don't think any of the skills that we identified seem wrong or out of date. They're all things that we need more urgently today than ever before. I think the balancing act we did in terms of acknowledging traditional research, traditional literacy, media literacy in relation to the new media literacy seems more as important, if not more so than ever before. This is an era of misinformation and disinformation. We need to have all of those skills to sort through what's going on day by day and the flow of information right now.

Tessa Jolls:I thought the skills you cited are all relevant and more important than ever, as you said. If anything, it is disappointing to me that we haven't made more progress, from the standpoint of institutionalizing new media literacies. You called for a systemic approach to education regarding the new media literacies. In some ways, I think we're still stuck right where we were. What do you think?

Henry Jenkins:The MacArthur Initiative, in general, identified large numbers of people who shared a common vision of what needed to be done and recruited a lot of individual teachers who were willing to take risks and experiment and do things in their classroom. At the end of the MacArthur-funded Digital Media and Learning Initiative, there is a much more, much stronger body of evidence in support of some of the hypotheses we put forth in that report. There were some nuances on how it needs to be taught and what it means to bring it into the classroom which are really significant.

What we didn't see was the institutionalization of it, the scalability of it. It's been hard to get even individual school districts on board. There's been good luck coming out of the Youth and Participatory Politics Initiative. Their Civic Tool Kit has been picked up in citywide or district-wide standards, but not on state or national standards so far. So in some ways, this experience taught me a lot about how hard it is to make institutional change in education.

Change still comes on the backs of individual teachers who are willing to do the hard work, to bring new resources and approaches into their school and to fight their department chairs and their principals in order to do something that still seems risky. It shouldn't be risky, this many years later. I think getting wide adoption is really, really hard and MacArthur pushed against that, and still didn't inspire much momentum. We're still seeing the Connected Learning Network trying to fight that battle and again, they are running up against a lot of stone wall.

Tessa Jolls: In the report, you also called for the informal learning environment to be involved. Do you feel that there's been progress in that arena or do you feel like it's pretty much the same story as formal learning, in terms of scaling?

Henry Jenkins: There have been some large scale initiatives, for example, the YouMedia project out of the Chicago Public Library. The MacArthur promoted this program and it led to many, many other libraries adopting that model. It may be the biggest success story coming out of Digital Media and Learning. The librarians have taken up the calling. I spent time after the report was released talking to library organizations and I found them much more receptive than teacher organizations. If anything the role of the librarian as an information coach has now been firmly established in the way they conceptualize themselves. Many of them have been really open to the new media literacies in one way or another. So definitely we had much more freedom outside of school than inside school through libraries and even through school librarians. You have more freedom than the sort of standardized educational test-driven curriculum, but there is so much more that should be done to fully integrate those skills into the afterschool space.

Tessa Jolls: Regarding institutional barriers, and you mentioned in the report that there's the participation gap the transparency problem, and the ethics challenge.

Henry Jenkins: Credibility issues seem more acute after 2016 and the misinformation campaigns and the debates about fake news and so forth. That's a huge problem that we're confronting today and we're realizing that our concerns are not just casual use of information but active massive misinformation campaigns that are undermining the idea of standards of truth.

Similarly, we need to address the intractability of the participation gap. This is what led me some years after the report to shift talking about living in a more participatory culture because that phrase means every time I say it, I have to call attention to who's left out, what groups are not allowed to fully participate, and what the barriers the participation look like.

Those barriers seem ever more real in the age of COVID. We wired the classrooms and promised people access to computers through libraries. Now we're hearing that as many as a quarter of students in LA don't have access to public education during the quarantine because they don't have home access. They can't go on Zoom calls with their teachers and participate with their classmates. They're locked-out. Regarding the most basic level of technological access, we are as bad as we've ever been in serving the needs of the lowest-income students. We're hearing stories of students writing papers on their mobile phones because they don't have access to computers at home. We're also seeing young people who lack mentorship. They need to fully understand the world they're traveling through and to have someone who's watching their back and giving them insight about some of the choices they're making along the way.

The ethics challenge increasingly came to focus on questions of mentorship because in the report we talked about some of the work that had been done on high school journalism as a space for mentoring future journalists. We called out the degree to which at least some young people had greater access to the communication capacity than ever before, and less mentorship than ever before. The research I've seen more recently shows that this is still the case, that most young people don't have access to mentors who can help them confront the challenges they encounter as they move through the world online.

Looking back, I don't think we understood the full complexities of the picture. I think the fact that since this systemic racism, for example, doesn't surface anywhere in the report. We understood the participation gap almost entirely in terms of economic barriers to access. Today, it's clear that it's not just access to technology, it's access to knowledge and skills, but it's also access to certain kinds of privilege. It's access to people who are willing to listen and respond to what you have to say. If the message given is that what you say is unimportant because of the color of your skin, then that outweighs almost anything else we do in the space of new media literacy. That problem is more and more visible to us today than it was when we were writing that report, and I feel we were almost naive when I reread the report.

Tessa Jolls:Interesting. Yes. We need to give hope to everyone and yet it has to be a real hope in terms of our culture, in our leadership, in our mentors, and being open to listening and exchanging ideas.

Henry Jenkins: It doesn't do anything to ensure a voice for everyone if people aren’t making ethical commitments to listen to each other. Without that commitment, what I say about participatory culture as a learning environment is at best a set of ideals and not a description of reality. Students can develop a document to send government officials or a newspaper and even their own parents, but if they don’t get a response back, then is anyone listening? That's a big problem for us as a society. So to have a participatory culture there has to be a reciprocity of communication. This is something that Nico Carpentier and I have been talking about a lot in recent years. How do you build that willingness to listen and willingness to hear? Otherwise, you've just got noise and to some degree, the divisiveness of Twitter grows out of that sense of growing frustration with lots of people talking and no one's hearing what it is they have to say.

At the same time I'm seeing the updated numbers on young people producing media. I had a chance to observe it in an interesting way. When I traveled to India three years ago, an anthropologist took my wife and me into the center of one of the biggest slums in India, where they filmed Slumdog Millionaire. We went into homes of people and talked to young people about their use of technology. Even under those conditions most of the young people we talked to had made some media. There was a really powerful story of a young man, who told me his best friend had died of tuberculosis. A friend of his had access to an office and smuggled the man at night so they could use the office computers to produce a video tribute to their friends from footage shot using cell phone cameras and put it out on YouTube. So that was a really powerful story to me of the young people fighting against every circumstance to create and share something with the world, but you see so many other young voices being unheard, despite all of that.

Tessa Jolls: In the report, there was a statement that we should look at the new media literacies as a social skill. In a sense, I think that's exactly what we're talking about here. There are social skills that are involved in speaking and listening and being respectful and having dialogue and using all kinds of different ways of communicating, whether it's transmedia or whether it's a particular form of media. So could you comment on that a bit?

Henry Jenkins: If we look at traditional print-based literacy, it could be understood as an individual skill. I think that grew out of the fact that most people lack the capacity to communicate beyond an immediate circle of friends and family. So reading was understood as reading things that had been produced by someone else. Writing was understood as writing letters or maybe at most writing a letter to the editor of the local newspaper. There was almost an assumption that literacy didn't have large-scale social and cultural effects. In a networked society, we need to think of literacy as a collective experience, not just an individual experience. So we look at a world where all the research shows young people get their news not by sitting down and reading the newspaper in the morning by grazing information throughout the day through social media. So, what they see of the world is what their friends pass along to them. A sense of social accountability/responsibility needs to go hand in hand with this expanded communication capacity.

When we live in a world where hate speech has such an enormous, divisive effect on the culture then understanding the consequences of our own speech is really important. That has to be understood in the social context and not just an individual context. The problem is people see it as, "Oh, that is just my personal opinion or I was just expressing myself." They are not necessarily thinking of themselves is part of a larger information echo system that has a ripple effect across the world.

Tessa Jolls: That too, is a very important point for today's society and the way that we use technology. It also builds on an idea that you introduced in the report, which was that we should be expanding literacies, not pushing aside literacies. So, in other words, with the new media literacies, we should be looking at enhancing people's ability to critically engage, to be able to understand that social context. You put your finger on the pulse! Henry, where do you see the field going at this point? Having taken this look back, when you look forward, what do you see it? Do you feel that the report is a guide to that future?

Henry Jenkins: My own current work for the last how-many years has been in the area of civics, which picks up on a number of the themes from the report. When I re-read the report, I see my current thinking about the civic imagination as in some ways growing out of the discussion of play and out of the discussion of performance, but also, the act of imagining is something that is not in that report. I wasn't sure what skills I would add, but I find myself pondering whether something like imagination or world-building is not a skill that is more visible to us today than it was when we wrote that report. That skill set is one that in fact, I am spending much of my time working on, not just helping students or young people think about it. We certainly are still doing work with schools and libraries and after-school programs. We are also working with adult communities. We have done workshops with churches and mosques. We have done activities with governmental officials. We have done activities with labor unions. We have done projects all over the world on thinking about the civic imagination.

In some ways, this new work is an extension of the toolkit that we identify in that report. It is designed to specifically enhance the sense of possibility within the culture at large, and particularly the sense of civic connection. In that way, the sense of civics I am talking about in our new work probably connects with the social skills and cultural competency we are describing here. We are trying to figure out what the skills are that we need to live with each other, rather than continually grinding down at the core of our democracy with each election cycle and every battle in between, to the point that we are no longer speaking to each other. To me, that is the most urgent thing. In some ways, that is about extending our notion of new media literacy, to talk to adults as well as young people. All of us in our society need networking skills, negotiation skills, judgment skills, as we process this new world we are living in. Now, we need to figure out how to inhabit a global society, and within the United States, to live in a much more diverse society than many of us grew up in.