Global Fandom: Libertad Borda (Argentina)

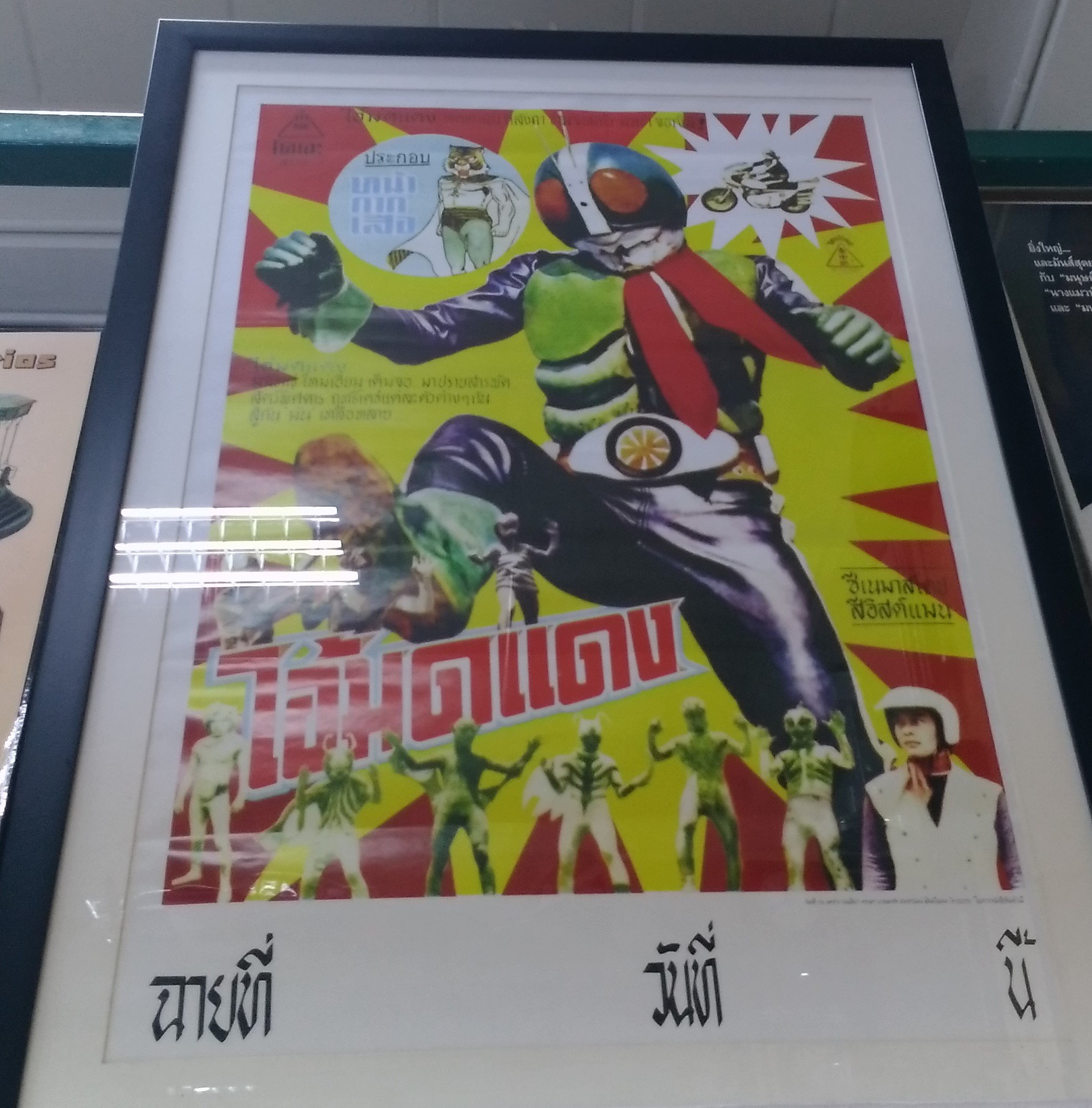

/A handwritten note (The Peronist Box) advertising cheap items in an anime convention in Buenos Aires (Photograph: Gerardo del Vigo).

Although it has become more and more difficult to establish a clear correlation between fandoms, practices and national roots, mainly for online researchers, I am going to speak from the perspective of the Argentine context. But in the first place, I would like to summarize the hypothesis built in my PhD dissertation (2012), which was a theoretical input for other researchers whom I was honored to tutor in their graduate and postgraduate works. In dialogue with the different trends within fan studies literature, I ventured the idea that the fan phenomenon [fanatismo] has become a true pool of diverse resources (comprising attitudes, expectations, practices, and relational modes between peers and with institutions) which increasingly contributes to the creation of individual or collective identities. I borrowed this expression from E.P. Thompson (1990) with the intention of addressing some of the criticism directed at previous academic approaches and moving away from the reference to a condition corresponding to a certain “type” of consumer. In these observations I made a provisional list of the items in that pool, which is constantly growing or being restructured. Among many other items, the list included elements such as enunciative and textual productivity, the building of community and reciprocal ties, modes of performance. The main objective of this enumeration was simply to highlight the fact that there were no a priori hierarchies among items: against any prescriptive or normalizing notion of fans, this hypothesis proposes that we cannot predict whether they will be “textual poachers” like the DeCerteausian consumers, industry watchdogs or any of the multiple possible grades between the two.

Which will be the combination of ítems and the direction the fandom or fan in question will go? Will they appropriate the text in an escapist way? Will their reading be resistant? Will they form a subculture with their peers? Will they be functional to industry interests? Will they generate new practices opaque to the eyes of that same industry? There are no answers previous to field analysis, as it will all depend on the specific configuration of the historical context, industry conditions, former fan experience of the members and, very importantly, some other cleavages like gender, class, or race.

Another key aspect of this proposal is that though this pool of resources was firstly sketched by fan actions, today it is also available for the industry itself. Industry always took fans into account, providing them with material and taking advantage of their networks. However, this was a relationship with fans who were already self-identified as such, because the main aim was to gain bigger and bigger mass audiences, and they considered fans as enthusiastic, though eccentric, disseminators, who helped in this process.

Today, though mass production is still an intrinsic drive for industry, fans clearly stopped being the marginal helper who knocked at the back door to become a key word in marketing lingo, not only in entertainment but also in all economic fields (“turn customers into fans” is today’s marketing mantra). Thus, fanification of audiences is another step in the process of commercialization. Industry strategically selects resources, discarding those which do not guarantee control over the activity they encourage.

As from this general theoretical basis, my research group has been able to find common grounds for local studies on very different fandoms such as music fandoms (cumbia and romantic music fans), media fandoms (comprising such diverse objects as global franchises and local TV genres), and soccer fandom.

Now that I have outlined theses general premises, I would like to make three specific observations:

1) Nominalization issues: In the so called peripheral countries (as opposed to central ones, but mainly to US central position), fan studies researchers experience an extra challenge which is the linguistic mismatch as regards English lexicon. For decades, in Argentina the term used was “admiradores” [admirers], and when “fan” began to get used, it was only restricted to club membership. To add further confusion, “fanático” was also used, and this probably contributed to fuel both the religious overtones in media representations, stressing the negative aspect of the practices. It was approximately around 2000 that “fan” started to encompass a more neutral meaning. In the sports field this mismatch is even larger, because “fan” was only incorporated in recent years and its use is still limited. Soccer fans (Argentina’s most popular sport) are named “hinchas”, and the fandom is “hinchada”. These terms tend to refer more to bodily practices and do not easily travel from offline to online. This fact may have influenced the special isolation of scholars who study soccer fans (a field with an important development in Argentina. Pablo Alabarces’s work, for instance) from other fan-related object researchers. Up to a point, the rejection of many soccer fans to be named as such is also found in scholars of that area, who avoid interacting with fan studies literature. We could also hypothesize a gender bias here, because “passion” for soccer is seen as a legitimate feeling whereas “adoring” a singer or an actor is still rejected as teen feminine irrationality (though with much less aggressiveness today) and, much more often, unproductive expenditure.

2) Transformation of objects and fandoms: Fandoms have always been prone to change, but sometimes the change in fandoms derives from transformations in the object itself. Such is the case of the Latin American TV genre knows as telenovela. As it has very often been remarked, melodrama is the Latin American cultural pattern par excellence, permeating languages, genres and even political and religious discourses. Telenovela has been its main exponent for decades and the online reactions of its audience was the focal point of my PhD work. Years ago telenovelas showed locations of nearby countries, such as Brazil, México or Colombia, and old telenovela fan forums (today practically non-existent due to new social networks such as Facebook or Twitter) brimmed with questions on the meaning of certain words not used in Río de la Plata (Argentina and Uruguay) Spanish, or of slightly different local habits. Currently, this situation has changed, mainly in Argentina, where very few telenovelas are produced today (even before pandemics) and the genre is no longer the transgenerational object it used to be–now it is relegated to lower income, older demographics. To make matters worse, new industry players made their way into the market, such as Turkey (today you can watch four Turkish soap operas a week in Argentine broadcast TV, and none from Argentina). So the old melodrama has moved to some very restricted spaces within streaming platforms, mainly Netflix. These platforms have a much lower share among the lower income sectors, which traditionally formed the core telenovela audience even when it was watched across different social sectors. On the other hand, the panorama of streaming platforms is completely different from that of television. US and other central countries shows take up the overwhelming majority of the options available, and local offerings face a David-Goliath fight, so they have to adapt to different production modes from those of the old national products. Thus, one of challenges facing melodrama fan researchers is to enquire how the sociocultural profile of this new fan has changed and which of the old fandom practices still prevail.

3) National peculiarities. Whereas fandoms tend to have common features worldwide, there are always peculiarities. Argentinians are often considered very politically minded, and youth plays an important part in political participation. So (party) politics is part of everyday social discourse and consequently it can crawl its way into many situations involving fan practices. For instance, six years ago when a new telenovela was announced starring actors and actresses who sympathized with Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (aka CFK, former President and today’s Vice-president), many genre fans who hated her announced an anti-fan campaign against the telenovela. So many CFK supporters took it as a sort of duty to watch it as part of its political obligations, and to advocate it in Facebook and Twitter. Unknowingly for most, they acted like a very vocal fandom.

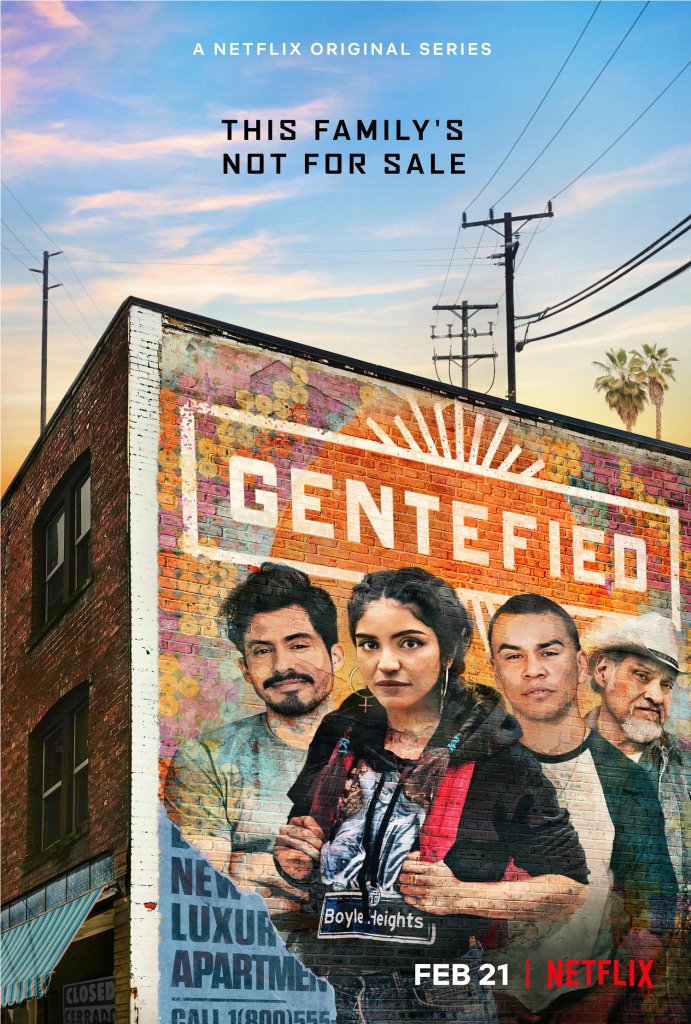

To give an example from a very different fandom, we can see party politics also making its way into local anime conventions. The use of Peronism as a synonym for cheap and popular (image 1), or the offer of “Otaku and Peronist” pins (image 2) are indicative of tensions within society in general but also within this fandom, which has, in the last two decades, witnessed the surge of new fans from a different social sector than that of upper and middle classes who used to form most of the fandom. This use is probably ironic for most Otaku, but there might be newcomers sincerely identifying themselves as Peronist.

Paradoxically, mainly due to the fact that fan studies are only beginning in Argentina, the questions posed by the link between fandoms and party politics, which are arising in other parts of the world, are still an unexplored field.

Libertad Borda holds a degree in Communication Sciences (Universidad de Buenos Aires, UBA) and a PhD in Social Sciences (UBA, 2012). Since 1998 I have been a faculty member in UBA, where the course name is Popular Culture and Mass Culture. The title of my doctoral dissertation was Bettymaníacos, luzmarianas y mompirris. El fanatismo en los foros de telenovelas and I coauthored with Federico Álvarez Gandolfi a collection of research works on fandom (Fanatismos. Prácticas de consumo de la cultura de masas, Editorial Prometeo, in press).

A pin sold in an anime convention in Buenos Aires.