Bringing Critical Perspectives to the Digital Humanities: An Interview with Tara McPherson (Part Three)

/A key debate running through the book has to do with whether digital media collapses or maintains medium specificity distinctions between older media forms. What do you see as at stake in this debate? Tara's introduction calls out the persistence of formalist theories, which pushed aside other perspectives in the early phases of this debate. Does medium specificity necessarily bring us back to formal concerns or can this concept be used to work through some of the issues of race and politics which you want to raise in the second half of the collection? I do not think that studies of form or of medium specificity necessarily push aside other perspectives nor are they inherently depoliticized. But I do think that a focus on form often has the effect of displacing long-standing insights about the dual imbrications of technology and cultural systems.

To return to the example of feminist film theory that I mentioned earlier, one of the key insights of research by scholars such as Laura Mulvey or Constance Penley was their fierce examination of the ways in which technological systems and aesthetic practices exist in tight feedback loops with cultural systems. Technological systems never exist outside of culture, yet many formal analyses of digital media in the late 1990s and early 2000s often seemed to replay the blindspots of structuralist theory.

Similarly, we see similar patterns today in certain formations of platform and code studies. There remains a persistent belief that race or gender or sexuality can be bracketed off while we attend to forms and technological systems. This belief is only possible because it tends to treat concepts like race or gender at the level of content rather than at the level of form or system. In such a paradigm, you might make a video game or an exhibit about race but would see the forms or technologies as neutral delivery systems.

I don’t believe that our technologies and aesthetic forms are neutral or innocent. If Mulvey helped us see that Hollywood cinema naturalized a male gaze, aligning technological form with cultural systems, we might also ask to what degree our computational systems both reflect and shape broader cultural systems of meaning.

In my work on the origins of the operating system UNIX, I argue that early developments in digital computing were also intertwined with shifting racial codes in the U.S. and beyond. The introduction of digital computer operating systems at mid-century installed an extreme logic of modularity and seriality that “black-boxed” knowledge in a manner quite similar to emerging logics of racial visibility and racism at that time.

There is something particular to the very forms of the digital that encourages just such a partitioning, a portioning off that also played out in new configurations of the city in the 1960s and 1970s, in the increasing specialization of academic fields, and even in the formation of many modes of identity politics. In that work, I’m interested in understanding race as an operating system of a different order, one that shaped the very development of computational systems. Race (and gender and sexuality) are not just relevant at the level of representation, i.e., as images on our screens. They also form the ground from which our technological systems emerge. I think it would be naive to imagine that our digital systems remain somehow pure and disentangled from broader cultural systems of meaning and power. Thus, I am very interested in media specificity; I just understand this specificity to always exist within and to be shaped by broader cultural and historical contexts.

[video width="480" height="269" m4v="http://henryjenkins.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Digital-Dymanics.m4v"][/video]

This belief actually structures the technological development of software in our lab. Our work on Vectors very much aimed to integrate form with content, that is, to think through how a project’s formal structure and interface design reflected its content and vice-versa. So, a project like Kim Christen’s “Digital Dynamics Across Culture” models the unique systems of belief and of shared ownership that underpin Warumungu knowledge production and reproduction, including a system of "protocols" that limit access to information or to images in accordance with Aboriginal systems of accountability. The user experiences it constructs are partial, embedded, and provisional, sometimes barring access to specific images or performances in a manner consistent with the logics or protocols of the Warumungu people. The project’s information design as well as its aesthetic design (to the extent we can even separate these) render Christen’s argument differently than a print article would. Following her fellowship at Vectors, Christen went on to lead the team that developed Mukurtu, a content-management system that allows indigenous peoples to create collections of material that respect their cultural protocols and knowledge systems, limiting access when appropriate.

Scalar Platform — Trailer from MA+P @ USC on Vimeo.

Rather than assuming that technologies are neutral systems that need only be studied formally, humanities scholars should study technologies to understand how they shape and are shaped by culture. For instance, Wendy Chun’s recent book mines the connections between the rise of digital computation and of modern genetics. And we can do more than study technology. We can also participate in the design and building of technological systems that reflect both our ideological and our theoretical allegiances.

Over the past five or six years, the work in our lab has centered on developing Scalar, a new authoring and publishing platform that was released into open beta in spring 2013. Scalar allows scholars to create with relative ease long-form, multimedia projects that incorporate a variety of digital materials while also connecting to digital archives, utilizing built-in visualizations, exploring non-linearity, supporting customization, and more.

Scalar is a direct outcome of our work on Vectors as well as with our collaborations with many other scholars. We learned from those collaborations that the rigidity and hierarchal structure of many software platforms were ill-suited to the aims of qualitative humanities scholarship. Scalar is meant to be more flexible; its very technological design reflects years of work with scholars invested in feminism, post-colonial studies, activism, critical race theory, and post-structuralism. Scalar is also part of a larger network, the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, a partnership that includes several academic presses, archives, and humanities centers. One of our goals is to help push forward the conversation around open access in scholarly publishing. We also are deeply interested, as we are with Vectors, in emerging genres for scholarship, genres that move beyond a singular focus on text to explore other ways of knowing and of communicating information.

Tara, both here and elsewhere you've stressed the ways that digital theory often displaced issues of gender, racial, sexual, and class differences in favor of a kind of universialized subject. Why do you think this displacement occurred? What are some of the strategies you and the contributors to the book have taken to reassert a politics of difference into the conversations around digital media?

My previous response gets at some of the reasons why I think these displacements occurred, coupled with the limiting language of the digital divide that got deployed in the late 1990s (something I discuss in my essay in Transmedia Frictions.) As far as strategies go, several of the Transmedia Frictions authors reject a depoliticized approach to digital media theory, particularly vis-a-vis race. Some essays explore race and the digital through examinations of identity and representation, but others investigate the relationship of race to technology along different registers and also enrich our conceptions of the political.

Patricia Zimmermann and Josh Hess turn our attention to a series of digital documentary projects that activate a transnational imaginary that remains cognizant of the specificities of location and embodiment. They deploy the concept of the fold and of the sphere, powerful ways to think the relation of form to content, technology to culture, and past to future.

In his contribution, Herman Gray urges us to see the multiple valences of technological devices, recognizing their complicity within capitalism as well as their potential to (at least in the moment) crystalize new relations. John Caldwell and Guillermo Gómez-Peña/Rafael Lozano-Hemmer celebrate the possibilities of the low tech and the hybrid for ethnic cultural production, if in quite different ways.

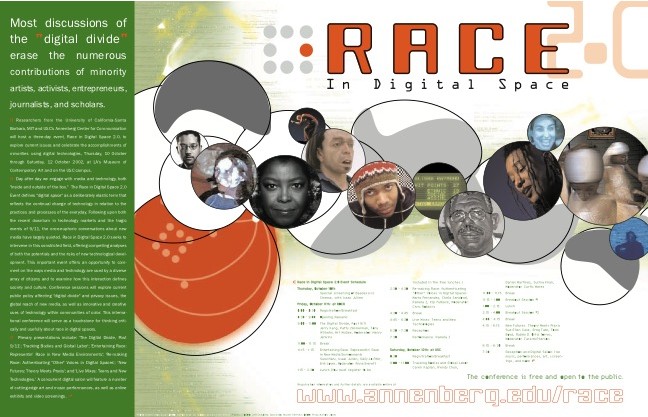

My frustration with the depoliticized nature of certain strands of digital media theory circa 1999 was a key reason I was so interested in collaborating with you, Anna Everett, Christiane Robbins, Erika Muhammad and others on the two Race in Digital Space events we organized at MIT in 2001 and at USC and MOCA in 2002. Those two events brought together such an incredible group of scholars, artists, activists, and policy makers. From Isaac Julien, Rubén D. Ortiz Torres, and DJ Spooky to Wendy Chun, Chela Sandoval, and Lisa Nakamura, and many, many others, those events captured the energy and momentum of Interactive Frictions but also centered their critical and creative force squarely on race.

There's a recurring interest throughout the essays, in both parts of the book, in issues of cultural memory, the archival, and the documentary. What new models have emerged over the past decade for thinking about the relationship between the digital and our collective understandings of history?

Our everyday interactions with the digital these days are so often about managing data and building collections. The enormous popularity of Flickr or of Instagram reveals an archival impulse writ large across culture, even if this impulse does not always attend to preservation or to metadata in the ways our “official” archives strive to do. We found this attention to collections to be a strong trend among our Vectors’ fellows. Our scholars often came to us with desire to animate a personal archive of some type.

They may have collected a vast array of materials as evidence for a print project, as was the case with Alice Gambrell’s “Stolen Time Archive.” She aimed to attend with care to a trove of materials she’d brought together in working on a book project. Many of these materials would not be included in the book, but Alice wanted the materials to have a life of their own. Her Vectors’ project simultaneously structures the materials, staging an implicit argument, while also allowing the user to roam the materials in relatively open ways. Her argument subtly builds as the user explores.

The radical archivist, Rick Prelinger, brought to us a collection of ephemeral film materials. He’d woven these materials into a linear film, but for Vectors he wanted to break the film apart again, giving the materials new life in an interactive interface. His project, “Panorama Ephemera,” is also a manifesto about the archive in the era of digitality. In the piece and across his career, he argues that archives are justified by their use and urges us to move beyond our conceptions of the archive as a closed and cautious place.

The feminist scholar Jennifer Terry sought to make sense of a collection of videos created by U.S. soldiers during the Iraq war, often called the first YouTube war. Her interventions in “Killer Entertainments” are both as an aggregator who brought the materials together from various sites and as an interpreter or curator who helps provide critical context for our engagement with the visual productions of wartime. Across these and other Vectors’ projects, scholars and designers explored new interactive possibilities for the archive, rejecting the archive as a neutral space and instead articulating archives with multiple points of view.

Marsha and Lev Manovich have rather famously dueled over the relationship of narrative to the database in computation. The past decade definitely reveals to us that these two terms are relational, not oppositional. The digital archive (as database) invites narrative, but it also often exceeds the contours of narrative. It can be both a collection and the stories we tell about that collection.

We are very interested in the possibilities for the digital archive as we develop Scalar. In our engagements with the archive, we both draw from our team’s work on Vectors and from a long tradition of digital archive creation in the early years of the computational humanities. Our interest takes several forms. First, Scalar actually connects to a few digital archives as one of its core functionalities. When authoring in Scalar, you can easily search in collections at the Internet Archive, Critical Commons, the Shoah Foundation, and the Hemispheric Institute, among others. We’ve built formal relationships to these archives and technical bridges to their collections.

When working with materials from these collections, the digital object stays in the archive (even as it seems to be incorporated into Scalar), but Scalar grabs the metadata about the object, preserving a set of contextual materials. So often, the things we grab from around the internet lose their provenance. Our technical design director, Craig Dietrich, implemented Scalar so that context could be respected and sustained along several levels. Scholars can also work with materials from several archives (or anywhere on the web) within a single project. In this way, Scalar facilitates aggregation across archives.

A second way that Scalar relates to the archive is that the projects designed in Scalar might themselves function like small (or large!) archives or exhibits. As with Vectors projects, some scholars we have collaborated with on Scalar are interested in allowing the users or readers of their research to engage with their primary evidence while also exploring the scholar’s own interpretation of that evidence. Scholars can collect sets of visual materials from various digitized collections into a Scalar project and then arrange the materials in multiple ways, creating interpretative slices or pathways through the collection. The project’s reader might simply browse the collection freely, but she might alternately follow the scholar’s analysis of the materials. Such a project is neither solely a book nor solely an archive, neither simply narrative nor database, but rather a hybrid space between the two that integrates scholarly analysis with a rich trove of primary materials.

Using Scalar’s built-in commenting features, the reader of the project can then add her own commentary, providing more context for the collection of primary materials or responses to the scholarly interpretations of the collection. One such project, “Performing Archive: Edward S. Curtis + ‘the vanishing race,’” brings together from several collections nearly 2500 image and sound files of the work of Edward S. Curtis, an early 20th century photographer. It presents the materials as a collection but also “slices” through the archive via several interpretative pathways authored by various contributors. Such work models a future for scholarship where our analyses might live more organically with our evidence, enriching the archival object and allowing viewers to test our interpretative claims. For humanities scholars, our archives are our datasets. The digital can afford us new ways to investigate, analyze and share these archives, alongside more traditional approaches.

Tara McPherson is Associate Professor of Critical Studies at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts and Director of the Sidney Harman Academy for Polymathic Studies. She is a core faculty member of the IMAP program, USC’s innovative practice based-Ph.D., and also an affiliated faculty member in the American Studies and Ethnicity Department. Her research engages the cultural dimensions of media, including the intersection of gender, race, affect and place. She has a particular interest in digital media. Here, her research focuses on the digital humanities, early software histories, gender, and race, as well as upon the development of new tools and paradigms for digital publishing, learning, and authorship.

She is author of the award-winning Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Duke UP: 2003), co-editor of Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture (Duke UP: 2003) and of Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, The Arts + the Humanities (California, 2014), and editor of Digital Youth, Innovation and the Unexpected, part of the MacArthur Foundation series on Digital Media and Learning (MIT Press, 2008.) She is currently completing a monograph about her lab’s work and process, Designing for Difference, for Harvard University Press. She is the Founding Editor of Vectors, a multimedia peer-reviewed journal affiliated with the Open Humanities Press, and is a founding editor of the MacArthur-supported International Journal of Learning and Media (launched by MIT Press in 2009.) She is the lead PI on the new authoring platform, Scalar, and for the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture. Her research has been funded by the Mellon, Ford, Annenberg, and MacArthur Foundations, as well as by the NEH.