Desert Island Comics (Issue 1) Joan Ormrod

/Image designed by Rutherford.

Like many comics readers, I love hearing recommendations from other scholars and fans. It’s never healthy for the bank balance, but as Henry once said to me, “it’s expensive if you do it right.” (He was referring to superhero comics, but the sentiment is true for the medium in general, I’d say). Over the past two weeks, I’ve been involved in the virtual book-club on Henry’s new monograph, Comics and Stuff, and let me tell you: it’s a dangerous place to be! With so many references and recommendations flying around, I found myself heading frantically to online shops afterwards. (I know, I know, a first-world ‘problem’ to be sure.) One thing is abundantly clear: we’re gonna need a bigger house!

To RSVP for the final panel on Tuesday June 30th at 10 a.m (Pacific ST)/ 18:00 (British ST), head here to register for the Zoom link. We would be honored if you would join us.

When Julia Round and I ran a series on British Comics late in 2019 on this website, I began asking contributors to discuss some of their favorite comics, comic strips, and/ or graphic novels. In today’s first installment, we have Dr Joan Ormod sharing some of her favorites (and it’s great to see Bryan Talbot’s Alice in Sunderland in there, which is one of Henry’s case studies in Comics and Stuff).

—William Proctor, Associate Editor.

Joan Ormod

It’s tough deciding on the top five comics and so I tried to have a reasonable spread of comics that have inspired or awed me. The choices are in no particular order but can be viewed in linear time. So, some of the first comics I read to the latest. One thing I noticed is the necessity of the words and images working together and the first of these choices illustrates this really well.

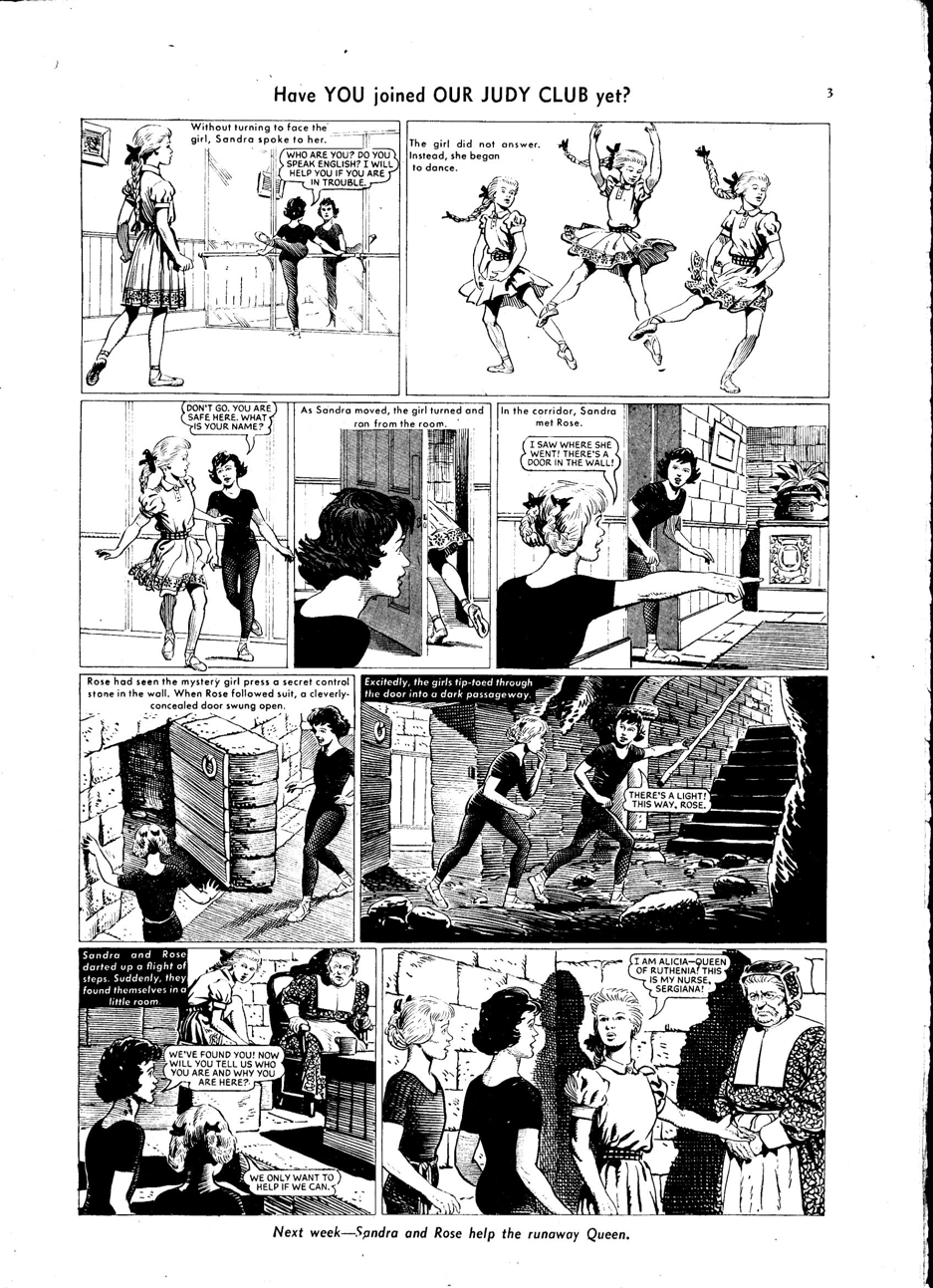

1. ‘Sandra of the Secret Ballet’ – art by Paddy Brennan, story unknown

Sandra Wilson appeared in Judy from issue #1 (16/01/1060) and for most of the 1960s to the 1980s, the latter in reprints of the earlier stories when Judy merged with Emma. She was a great role model for girls in that era as she was brilliant dancer, created ballets and had adventures (not for her a husband two children and domestic bliss).

Her first adventure was to be kidnapped by Nina Sierra, a famous ballerina, who spirited orphans away from their abusive homes and trained them to become ballet dancers. Ok so in the post Jimmy Savile era there would be all sorts of social services and police investigations going on but this was the innocent 1950s. The stories and the images worked organically – Paddy Brennan was, in my opinion, the best artist at representing ballet. Ron Smith who drew the much more famous Moira Kent, just couldn’t get the feet and the positions right. It is such a shame that the writer was unknown, but they obviously knew what would appeal to young girls – a secret castle on a secluded island, loads of orphan girls who were fabulous dancers and a heroine who toured the world, saved her ballet teacher from ritual sacrifice in Spain and foiled numerous evil plots.

There was also a cast of visitors to the castle from Boris Rambine (modelled on Boris Karloff) who hypnotised the girls, a princess in hiding and a Billy Butlin clone who wanted to turn the castle into a holiday park. Somehow the series lost its magic when Sandra graduated and became a star.

I have included a few pages of Sandra stories. From #30 (06/08/1960), pages 2 and 3 – this is the story that introduces Alicia, queen of an Eastern European country, who happens to be a brilliant dance in hiding in the castle.

Brennan is a master of the black and white on the comics page and his drawings of the secret passages make you believe this is a real place.

The second story is the culmination of Sandra’s journey to Spain to save her dancing teacher, Nina Sierra from being forced to dance to death in the Ritual of the Flaming Sun. Gypsies in this story come from a long line of gypsies in British children’s literature. They were an exotic and ancient people with strange and sometimes cruel customs. Sandra, of course, saves Nina Sierra by taking her place and dancing through the night. Spain at this time was also an exotic destination as package holidays were only just becoming possible for mass tourists. Brennan’s use of tonal line work gives this story its atmosphere. Somehow, when his work was colored, for reprints in the 1980s, it lost some of its magic.

What I said earlier about the organic nature of stories and art can be seen in some of the Sandra stories with artwork by a different artist. They just weren’t the same.

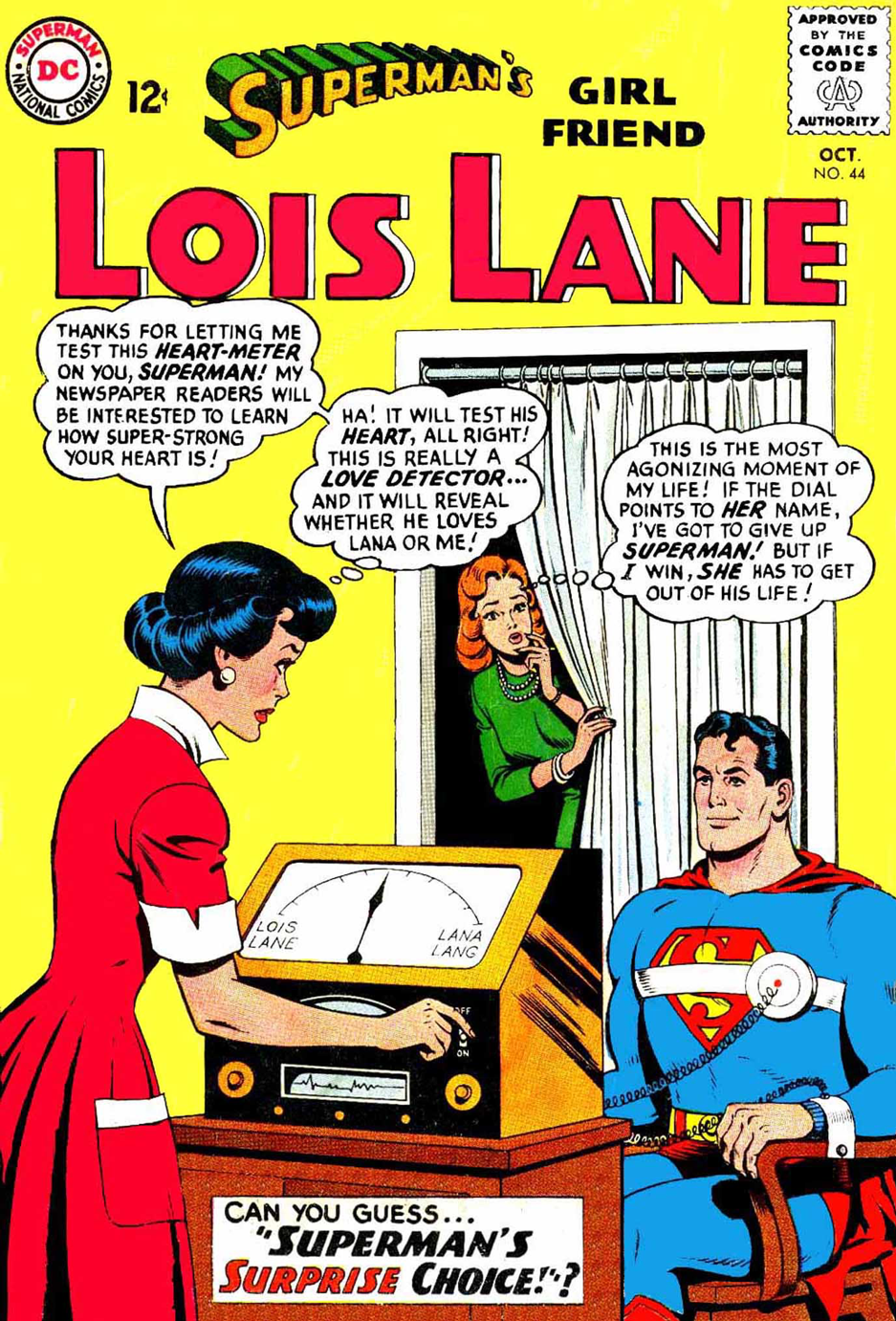

2. Lois Lane – art Kurt Schaffenberger, stories diverse

I included Lois Lane because of the art by Kurt Schaffenberger which fit the sappy stories so well. His style was clean and uncluttered and he seemed to take some of the idiotic stories seriously. Schaffenberger was one of the writers and artists who transferred to DC after Fawcett was closed when they lost a court battle against DC for copyright to Captain Marvel (now called Shazam). Some of the Lois Lane stories were written by Otto Binder, also from Fawcett and that innocent vibe from Captain Marvel comes through in a lot of these stories.

Superman and Lois Lane’s relationship was quite toxic. She was always being tested by Superman and punished for the most slight of reasons. It was similar to the sex comedies of Rock Hudson and Doris Day (without the sex, of course) in a battle of the sexes. Lois loved Superman but not Clark, Clark loved Lois but wouldn’t reveal he was Superman until she showed him she preferred him. The colour was startling on the news rack and much more glamourous than the UK comics which were often in black and white inside.

The editor of this series, Mort Weisinger, always had the most alluring premises. This cover from Lois Lane #44, October 1963 shows Lois and Lana Lang, her rival, tricking Superman into taking a lie detector. When I saw this cover in a newsagent window, I had to have the comic to find out whom he preferred. In 1964 comics were sold by the yard and you took pot luck which ones were available in any shop. Unfortunately, by the time I saved enough money to buy it, it had been sold and I never saw it again, until a few years ago when I managed to get a copy. You got your money’s worth too. There were three stories in each issue. Here’s the first page with Schaffenberger’s signature telephone panel. He was also allowed to sign his name – a practice that few artists were allowed to do until Marvel opened up the way for artists and writers to get credits.

3. Wonder Woman – art and stories George Pérez

I spent several years writing a book on Wonder Woman, a character who fascinated me as she was different from every other female character I’d encountered. I had a sneaky liking for the early 1960s stories on Paradise Island when she was written by Robert Kanigher and drawn by Mike Esposito and Ross Andru. But she never really came to life until the title was taken over by George Pérez in the 1987 post Crisis reboot under Karen Berger’s brilliant Vertigo line. For the first time the Wonder Woman I imagined became real. She was a naïve, kind and empathic person who was often bewildered by the cruelty and suffering she encountered in man’s world.

The stories by Pérez were sensitive and beautifully drawn but the characters came to life when he worked with Mindy Newall. The best of these was ‘Chalk Drawings’ (#46 September 1990) in which there is little superheroic action. In it, Vanessa, Wonder Woman’s young friend, attends the funeral of her best friend, Lucy Spears, a girl who has it all but who commits suicide. The story explores some of the toxic themes surrounding fame, fandom, beauty and consumerism. Lucy’s parent don’t understand why she committed suicide but the subtext tells it all, when someone has it all and its just never enough. Jill Thompson’s sensitive artwork was just right for this story.

4. Here – Richard McGuire

Richard McGuire’s ‘Here’ first appeared in Art Spiegelman’s Raw v.2, n.1, 1989. At first glance ‘Here’ (1989) appears an unremarkable (and rather confusing) account of the history of a space, rendered in a clean line style, each page consisting of 6 panels. However, the aim of Raw was to produce commix that pushed the boundaries of the medium and challenged the reader. ‘Here’ is certainly a challenging read for there is no clear cause and effect to direct the narrative and no protagonist to incite action. Rather, McGuire uses 36 panels to show the formation of the world, to reflect on evolution, vast time spans encompass the rise and decline of human cultures down to the lifespan of a human being. This comic is as much about time as ‘here’. It is impossible to describe a specific story from the comic but I love it because it show the potential for the form to express more than simple stories.

McGuire claimed he conceived the idea when he saw all the screens open on an Apple computer – a few pages show how this is reflected in the construction of the panels. He spent several years developing his original six pages into a book. The book does expand the ideas but, in my opinion, its nowhere as powerful as the comic. You can get the full six pages here

There is also a film produced by art students attempting to adapt the comic into a film:

An article by Chris Ware on the book Here; and a film of the book.

5. Alice in Sunderland, Bryan Talbot

Every Desert Island castaway needs a book that will keep them engrossed for many years (and doesn’t it feel like we’re in that situation at the moment when we are in lockdown? The one that I would still keep coming back to is Alice in Sunderland by Bryan Talbot. Like ‘Here’, Alice in Sunderland is more than just an exploration of Alice in Wonderland. It is about telling stories and is described by Talbot as ‘an entertainment’. He starts off in the Sunderland Empire introducing the reader to his stories. They span the history of the North East (which naturally draws me in since that’s where I come from), folk tales and legends such as the Lampton Worm (a precursor of Jabberwocky), the history of comics all wrapped into the story of the genesis of Alice. His art styles are gloriously diverse and experimental. His tales something like the Borges ‘Garden of Forking Paths’ with infinite possibilities and often ventures into cul-de-sacs and alternate storylines.

I enjoyed this so much that after reading it I tried to find some of the places in Sunderland. I have one disagreement with Bryan and that is in his affirmation that Bede lived in Sunderland. He lived for most of his life in Jarrow St. Paul’s monastery. Nevertheless, this book would keep me occupied for many years just in awe of its rich imagery and stories.

This page shows the complexity of the images as it collages photos, drawings and paintings on the page and shows the plasticity of the comics form.

This page is a mixture of different Bryans as audience member, as actor, as artist. It captures the fantastic nature of Alice in Wonderland’s dream world.

Returning to my original statement, it was only when I began to compile these comics that I realised how much I enjoy a comic where the art and story work well together. They are also inspirational. The list is unadventurous – Alice in Sunderland would likely feature in several top ten lists of any comics reader. But I make no apologies. The first two are comics I grew up with and inspired me to think beyond what was expected of me as a girl. Wonder Woman was meant to inspire women to become empowered. The last two are inspirational because they prompt me to think and wonder.

Dr Joan Ormrod is a senior lecturer in the Department of Media at Manchester Metropolitan University. She specializes in teaching subcultures, comics, fantasy and girlhood. She has published widely on these topics and she has edited books on time travel, superheroes and adventure sports. Her latest monograph, Wonder Woman, the Female Body and Popular Culture was published in February 2020 and is available now. Joan is the editor of Routledge’s Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics and she is on the organizing committee of the annual conference of Graphic Novels and Comics. She is currently researching girlhood and teenage comics in the UK 1955-1975.