More than Mere Ornament: Reclaiming 'Jane' (4 of 4) by Adam Twycross

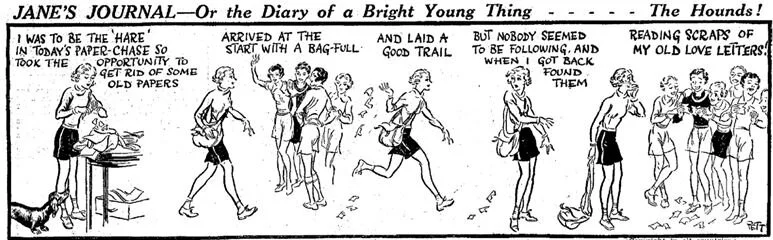

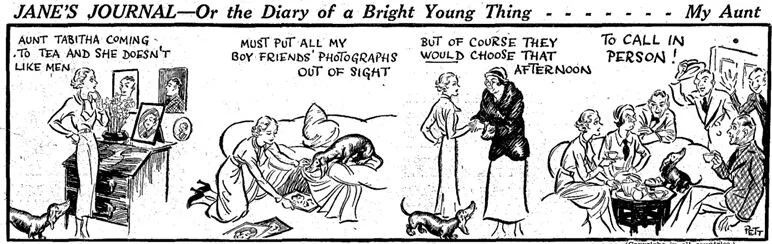

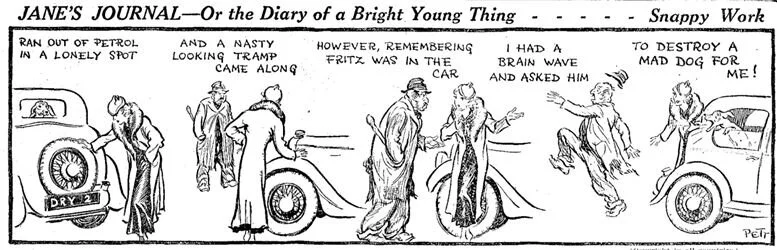

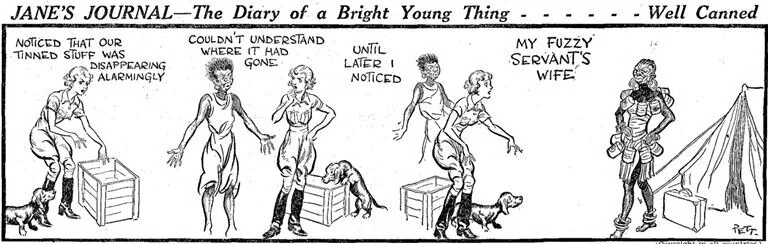

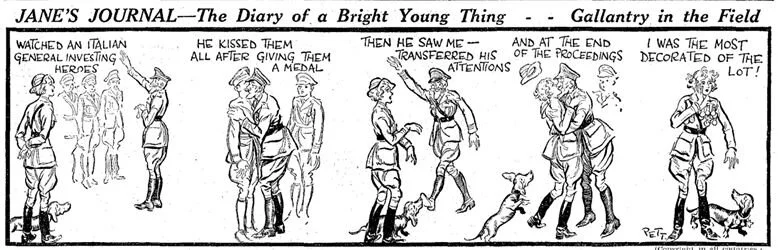

/Nudity was not the only development for Jane during the period of the Bartholomew revolution; as Rothermere’s influence receded and the Mirror increasingly aimed itself at working girls, the previous emphasis on Jane’s elevated social position was gradually replaced by a more down-to-earth characterisation that saw her take on a raft of paid employment. Between February and May 1936 alone, Jane tried her hand as a chorus girl, nurse, publican, rent collector, artists’ model, laundress, driving instructor and teacher.

A clear break with the past occurred on April 1st 1938, when a number of contemporaneous developments occurred for Jane. Behind the scenes, Don Freeman had been drafted in to help Norman Pett devise Jane’s scripts, and a young model named Chrystabel Leighton-Porter had become one of the series’ regular models (Fletcher 2011, p.84). Together the new creative team ushered in a raft of changes.

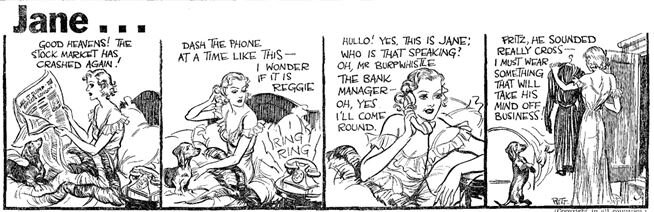

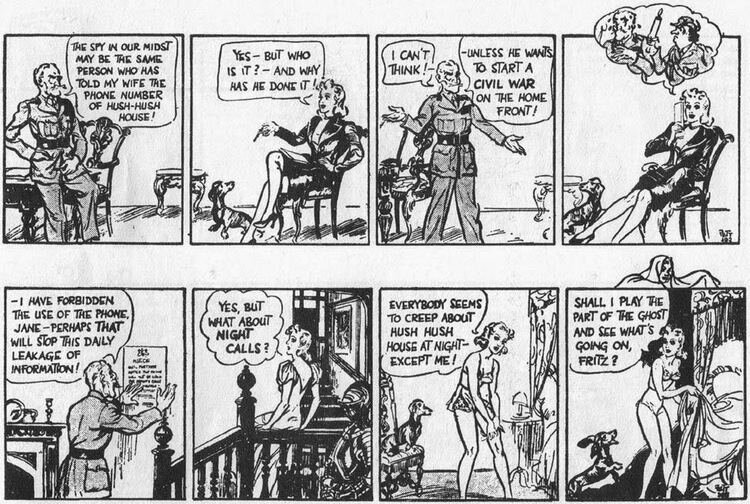

Pett 1938

Visually, Jane was remodelled, her bobbed hair becoming longer and fuller, and her silhouette becoming less angular and austere than had previously been the case. The series’ title was shortened to simply Jane…, the ellipsis introduced to indicate the intentional omission of the Bright Young Things reference that no longer reflected the character or social positioning of the strip’s star now that Rothermere’s influence was in the past. The format of the series also dramatically changed; gone was the diary format and the self-contained daily ‘gag’, replaced instead with an ongoing continuity format that saw the storyline unfold day after day. Each episode was also now clearly broken into panels, and the first person narration that had been one of the hallmarks of the series was replaced with direct speech, although it took a further two weeks for Pett to settle into a full use of speech balloons. Finally, within the fictional world of the strip, Jane herself underwent a transformation; ignoring previous continuity, expository dialogue in the opening episodes established that Jane lived in a northern town, where a private fortune had inured her to a life without the need for paid employment. A serious stock market crash, however, necessitated a fresh start, and Jane travelled south the start a new life in London. Over the following weeks, a new supporting cast was established, and Jane was remodelled as a continuity romance series, enlivened with plenty of comedy and regular nude and semi-nude appearances by its female cast.

Elsewhere, the storm clouds of war were brewing; in the world of Jane, all the elements that would make the series one of the great icons of the war were already in place.

References

Andrews, M and McNamara, S, eds. 2014, Women and the Media: Feminism and Femininity in Britain, 1900 to the Present, London, Routledge

Bingham, A., 2011, Representing the People? The Daily Mirror, Class and Political Culture in Inter-war Britain, In: Beers, L., and Thomas, G., eds., 2012, Brave New World: Imperial and Democratic Nation-Building in Britain Between the Wars, London, Institute of Historical Studies, p. 115.

British Cartoon Archive, 2016, Harry Guy Bartholomew (Bart) [online], Kent, University of Kent. Available from: https://www.cartoons.ac.uk/cartoonist-biographies/a-b/HarryGuyBartholomew_Bart_.html [Accessed 07/11/2019].

Chapman, J., 2011, British Comics: A Cultural History, London, Reaction Books.

Conby, M., 2017, British Popular Newspaper traditions, In: Palander-Collin, M., Ratia, M., and Taavitsainen, I., eds. Diachronic Developments in English News Discourse, Amsterdam, John Banjamins Publishing Company, p.127.

Cudlipp, H., 1953, Publish and Be Damned: The Astonishing Story of the Daily Mirror, London, Dakers.

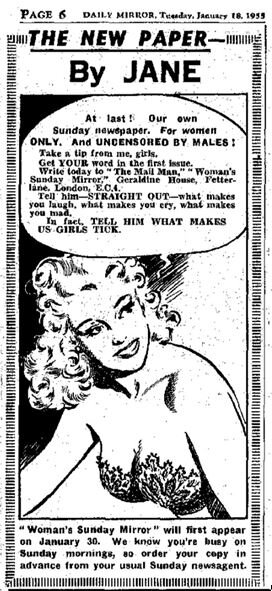

Daily Mirror, 1955, The New Paper By Jane, Daily Mirror, 18 January 1955, p.6(a).

Daily Mirror, 1934, Give the Blackshirts a Helping Hand!, Daily Mirror, 20 January 1934, p.6.

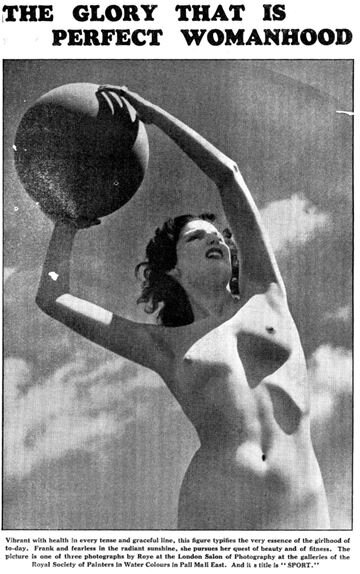

Daily Mirror, 1937, The Glory That Is Perfect Womanhood, Daily Mirror, 14 September 1937, p.14.

Daily Mail, 1994, D-Day: The Human Stories: Why I Stripped for the Boys: The Pin-Up Girl’s Story, The Daily Mail, 21 February 1994, p.33.

Fletcher, N., 2011. Jane, In: Gravett, P., ed., 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die, London, Quintessence, p.84.

Gore, I.P., 1931, Cabaret: More Revelry, The Stage, 8 January 1931, p.17.

Horrie, C., 2003, Tabloid Nation: From the Birth of the Daily Mirror to the Death of the Tabloid, London, Andre Deutsch Ltd.

Irish Independent, 1994, The Pin-Up Girl’s Story, Irish Independent D-Day Supplement, 1 June 1994, p.4.

Jones, M., 1982, Echo Woman: Jane in the Flesh, Liverpool Echo, 30 July, p.8

Levine, J., The Secret History of the Blitz, Available at www.amazon.co.uk/kindlestore.

Nicholson, V., 2011, Millions Like Us: Women’s Lives During the Second World War, New York, Viking Press.

Pett, N., and Freeman, D., Jane…, Daily Mirror, 7 June 1944, p.7.

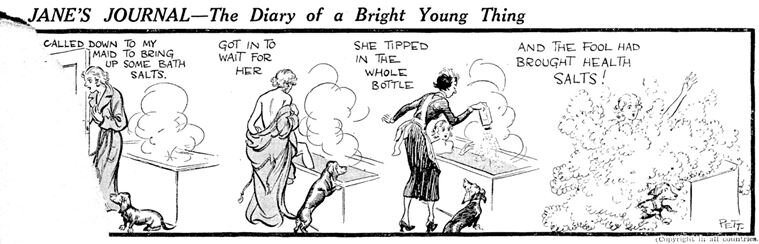

Pett, N., 1933a, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 21 June 1933, p.7.

Pett, N., 1933b, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 1 May 1933, p.7.

Pett, N., 1933c, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 8 July 1933, p.7.

Pett, N., 1933d, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 8 December 1933, p.7.

Pett, N., 1934a, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 23 February 1934, p.7.

Pett, N., 1934b, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 21 December 1934, p.7.

Pett, N., 1934c, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 5 April 1934, p.7.

Pett, N., 1934d, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 10 April 1934, p.7.

Pett, N., 1934e, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 27 October 1934, p.7.

Pett, N., 1934f, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 16 January 1934, p.7.

Pett, N., 1935a, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 30 October 1935, p.7.

Pett, N., 1935b, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 25 October 1935, p.7.

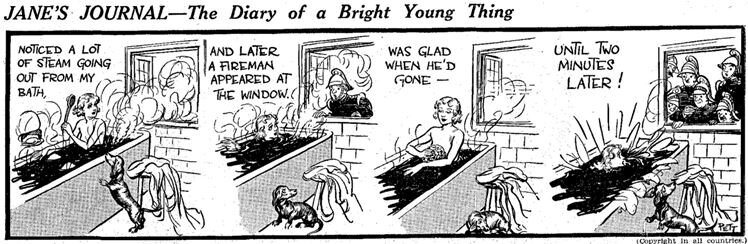

Pett, N., 1936a, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 9 July 1936, p.7.

Pett, N., 1936b, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 11 November 1936, p.7.

Pett, N., 1937a, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 11 March 1937, p.7.

Pett, N., 1937b, Jane’s Journal- Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, Daily Mirror, 28 August 1937, p.7.

Pett, N., 1938, Jane…, Daily Mirror, 1 April 1938, p.9.

Pilger, J., 1998, Hidden Agendas, New York, Vintage.

Radio Times, 1982. Jane’s Daily Strip, Radio Times, 31 July 1982, p.1

Ramsay-Kerr, J., Adventures Out Of My Own Set: No.III- The Dietists, The Sketch, 4 April 1928, p.4.

Saunders, A., 2004, Jane: A Pin-Up at War, Barnsley, Leo Cooper.

Shields Daily News, 1924, Bright Young People: Chasing Motor Clues at 50 Miles an Hour, Shields Daily News, 15 July 1924, p.3.

Smith, A.C.H., 1975, Paper Voices: The Popular Press and Social Change, 1935-1965, London, Chatto and Windus.

Stanton, B., 1937, Blame it on the Moon: Extracts from the Diary of Jean Hunter, Daily Mirror, August 2 1937, p.17.

Taylor, D.J., Bright Young People: The Rise and Fall of a Generation 1918-1940, Available at www.amazon.co.uk/kindlestore.