A Meme is a Terrible Thing to Waste: An Interview with Limor Shifman (Part One)

/I have to be honest that the concept of meme is one which sets my teeth on edge. Sam Ford, Joshua Green and I spent a fair chunk of time in our book, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, seeking to deconstruct the concept of "viral media" which has become such a common metaphor for thinking about how things circulate in digital culture, and along the way, we side-swipe Richard Dawkins' conception of the meme for many of the same reasons. Sorry, Mr. Dawkins, but I don't buy the concept of culture as "self-replicating": such a concepts feels far too deterministic to me, stripping aside the role of agency at a time when the public is exerting much greater control of the content which spreads across the culture than ever before. So, when I first met Limor Shifman at a conference held last summer by the London School of Economics, she knew I would be a hard sell in terms of the ideas being presented in her new MIT Press book, Memes in Digital Culture, but by the time our first conversation was over, she had largely disarmed my objections. She's done her homework, reviewing previous claims which have been made about memes, and reframing the concept to better reflect the practices that have fascinated many of us about how contemporary digital culture operates.

Her approach is direct, deceptively simple, but surprisingly subtle and nuanced: she recognizes that people are making active and critical choices about what content to pass along to others in their networks, but she also recognizes that they are making tactical decisions about how to design content in order to increase the likelyhood it will circulate beyond their immediate circles. She represents the new generation of digital scholars, who came of age with the net, and have largely absorbed (and thought through) some of the core assumptions shaping its many subcultural communities and their practices.

A part of me remains skeptical that given its historic roots, the term, meme, can be redefined as fully as Shifman wants to do -- or more accurately, as she claims has happened organically as 4 Chan and other net communities have applied it to their own cultural productions. Yet, I found much of what she wrote in her book convincing and think that this project adds much needed clarity to the conversations around memes, viral media, spreadable media, call it what you wish. If nothing else, her book provides an essential introduction to the ways genres operate in a more participatory culture.

I welcomed the chance to talk through some of these issues with her as part of this interview for my blog.

Let’s start with something basic. :-) How are you defining meme within the context of this book? How does your use of the term differ from the original conception of meme proposed by Richard Dawkins and his followers?

Basic question, complex answer… There is clearly a gap between the meme concept as it was defined by Richard Dawkins back in the 1970s and the term meme as it is used in the context of digital culture. My aim in this book is not to redefine the meme concept in its general sense, but to suggest a definition for the emergent phenomenon of internet memes. In other words, I limit myself to discussing memes in the digital world. I suggest defining an internet meme as (a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance; (b) that were created with awareness of each other; and (c) were circulated, imitated, and transformed via the internet by multiple users. So, for instance, I would treat the numerous versions of "Harlem Shake" as manifestations of one, particularly successful, internet meme. It is important to note that this definition does not equate internet memes with jokes – While many memes are indeed humorous, some of them (such as the "It Gets Better" campaign) are deadly serious.

This definition departs from Dawkins' conception in at least one fundamental way: Instead of depicting the meme as a single cultural unit that has propagated well, I treat memes as groups of content units. My shift from a singular to a plural account of memes derives from the new ways in which they are experienced in the digital age. If in the past individuals were exposed to one meme version at a given time (for instance, heard one version of a joke in a party), nowadays it takes only a couple of mouse clicks to see hundreds of versions of any meme imaginable (try, "Heads in Freezers", for instance J ). Thus, memes are now present in the public sphere not as sporadic entities but as enormous groups of texts and images.

If you are going to change Dawkins’ original formulation so dramatically, what is the continued use value of the concept?

The first answer to this question is that the term meme is a great meme. While widely disputed in academia, the concept has been enthusiastically picked up by internet users. It is flagged on a daily basis by numerous people, who describe what they do on the internet as creating, spreading or sharing "memes".

But there is also a deeper rationale for using this term. I think that internet users are on to something. There is a fundamental compatibility between the term "meme", as Dawkins formulated it, and the way contemporary participatory culture works. I describe this compatibility as incorporating three dimensions.

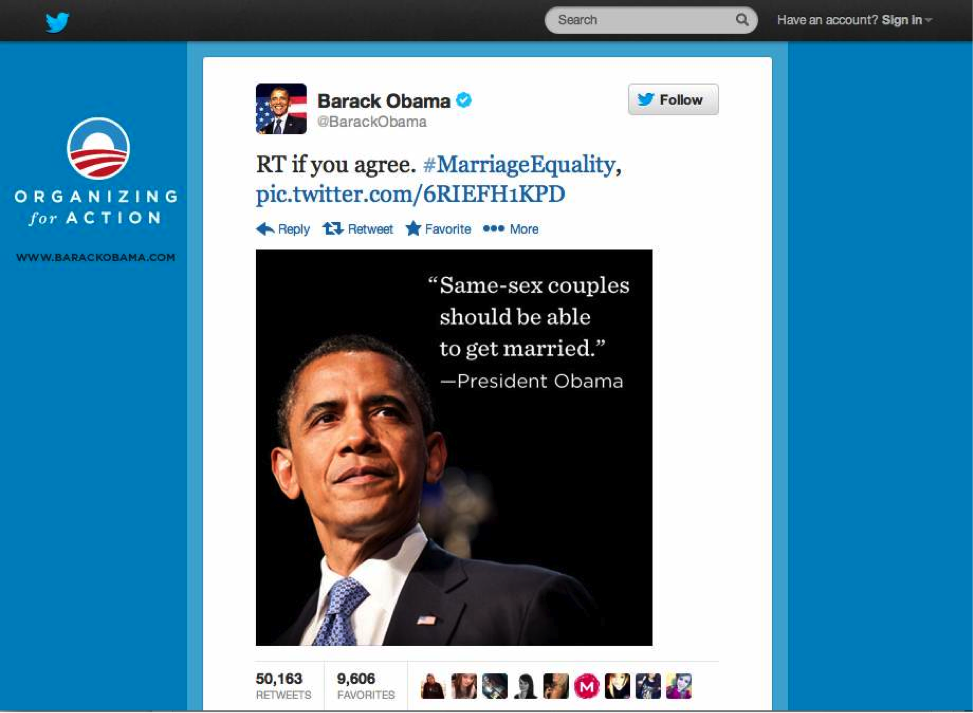

First, memes can be described as cultural information that passes along from person to person, yet gradually scales into a shared social phenomenon. This attribute is highly congruent with the workings of contemporary participatory culture. Platforms such as YouTube, Twitter or Facebook are based on content that is spread by individuals through their social networks and may scale up to mass levels within hours. Moreover – the basic act of "sharing" information (or spreading memes) has become – as Nicholas John suggests in recent articles – a fundamental part of what participants experience as the digital sphere.

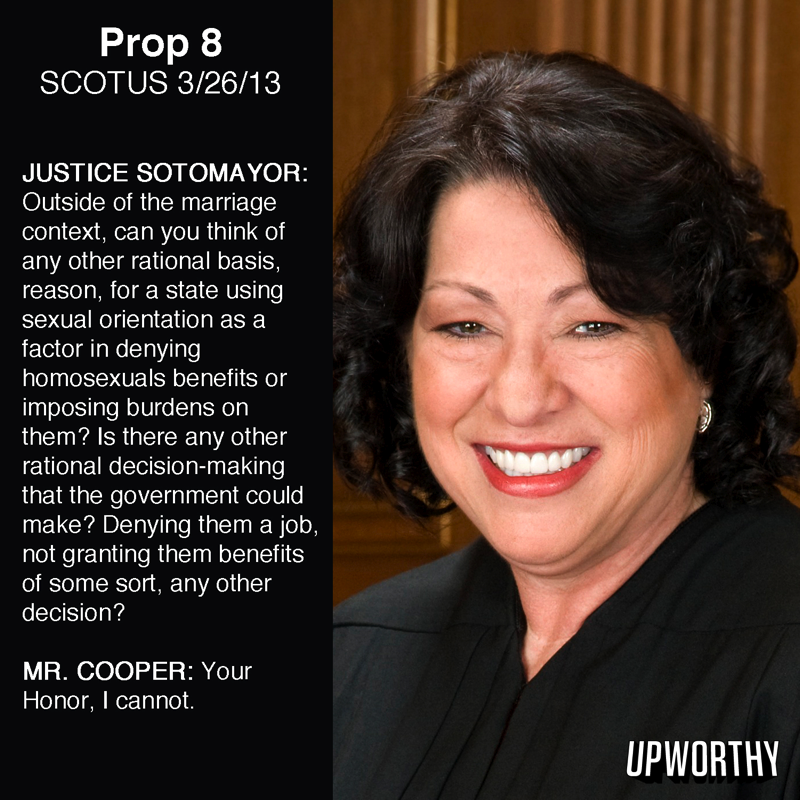

Second, memes reproduce by various means of repackaging or imitation: people become aware of memes, process them, and then “repackage” them in order to pass them along to others. While repackaging is not absolutely necessary on the internet (people can spread content as is), a quick look around reveals that people do choose to create their own versions of internet memes, and in startling volumes. People repackage either through mimicry (the recreation of a specific text by other people), or remix (technology-based manipulations of content, such as Photoshopping).

Finally, memes diffuse through competition and selection. While processes of cultural selection are ancient, digital media allow us to trace the spread and evolution of memes in unprecedented ways. Moreover, meta-information about processes of competition and selection (for instance "like" or "view count" numbers) is increasingly becoming a visible and influential part of the process itself: People take it into consideration before they decide to remake a video or Photoshop a political photo. In short, while the meme concept is far from perfect, it encapsulates some fundamental aspects of digital culture, and as such, I find it of great value.

In Spreadable Media, we make an argument against viral media -- and by extension, some hard versions of meme theory -- for their reliance on ideas of “self-replicating culture” which strip aside the collective and individual agency involved in generating and circulating memes. What roles does cultural agency play in your analysis of memes?

I could not agree more with the assertion underpinning your question. In my opinion, the problem is not with the meme concept itself, but with some of the ways in which it has been used, and especially those that undermine the role of agency in the process of memetic diffusion. In this regard, the argument that I develop in book largely follows the criticism that you raise in Spreadable Media. I call for researchers to jettison some of the excess baggage that the term has accumulated throughout the years, and to look at memes as cultural building blocks that are articulated and diffused by active human agents. This does not mean that people do not live in social and cultural worlds that constraint them – of course they do. Yet what drives processes of cultural diffusion is not the "mysterious" power of memes but the webs of meanings and structures people build around them.

Part of what I really value in your account is your stress on remixing and intertextuality within meme culture. As with all remixed culture, there’s a tendency for some to dismiss the lack of originality and “creativity” involved, yet you see these cultural practices as generative. Why is it significant that these shared genres or reference points keep recurring across a range of different communities and networks?

I'm glad that you raise this issue as I find it fundamental to the way that memes work. While people are completely free to create almost any form of content, in practice most of them choose to work within the borders of existing meme genres. This ostensive rigidity may in fact have an important social function: following shared pathways for meme production is vital for creating a sense of communality in a fragmented world. Moreover, these emergent recurring patterns – or "meme genres" – often reflect contemporary social and cultural logics in unexpected and interesting ways. Let's take, for instance, the "Stock Character Macros" genre: a set of memes featuring images of characters that represent stereotypical behaviors accompanied by funny captions. This list of characters includes, for example, “Scumbag Steve” (who always acts in unethical, irresponsible, and anti-social ways) and his antithesis, “Good Guy Greg” (who always tries to help, even if it brings him harm); “Success Kid” (a baby with a with a self-satisfied grin, accompanied by a caption that describes a situation that has worked out better than expected); and “Successful Black Man” (who comically subverts racist assumptions about him by acting like a member of the middle class bourgeoisie). While each of these memes may be of interest in its own right, it is their combination —or the emergent map of stock characters that represent exaggerated forms of behavior—that may tell us something interesting about contemporary digital culture.

Limor Shifman is a Senior Lectureer at the Department of Communication and Journalism, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She is the author of Memes in Digital Culture (MIT Press, 2013) and Televised Humor and Social Cleavages in Israel (Magness Press, 2008 [in Hebrew]). Her work focuses on the intertwining of three fields: communication technologies, popular culture and the social construction of humor. Shifman's journal articles explore phenomena such as internet-based humor about gender, politics and ethnicity; jokes and user-generated globalization; and memetic YouTube videos.