Cult Conversations: Interview with Julia Round (Part II)

/Unfortunately, the UK comics industry has contracted enormously today since the medium’s heyday between the 1950s and 1980s when comics racks and shelves were teeming with product on a weekly basis (many of which were a large feature of my childhood as well). Although The Beano and 2000AD are still being published in 2018, what is it about the British comics industry that continues to demonstrate its value for scholarly investigation?

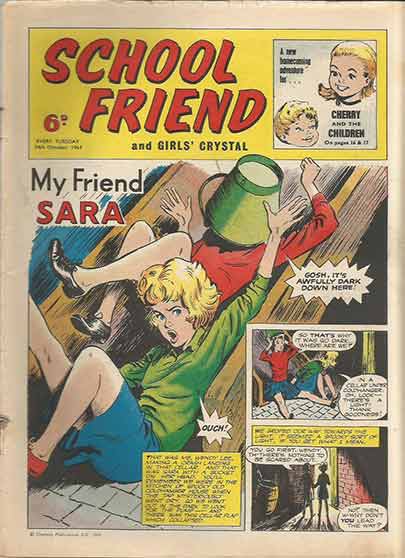

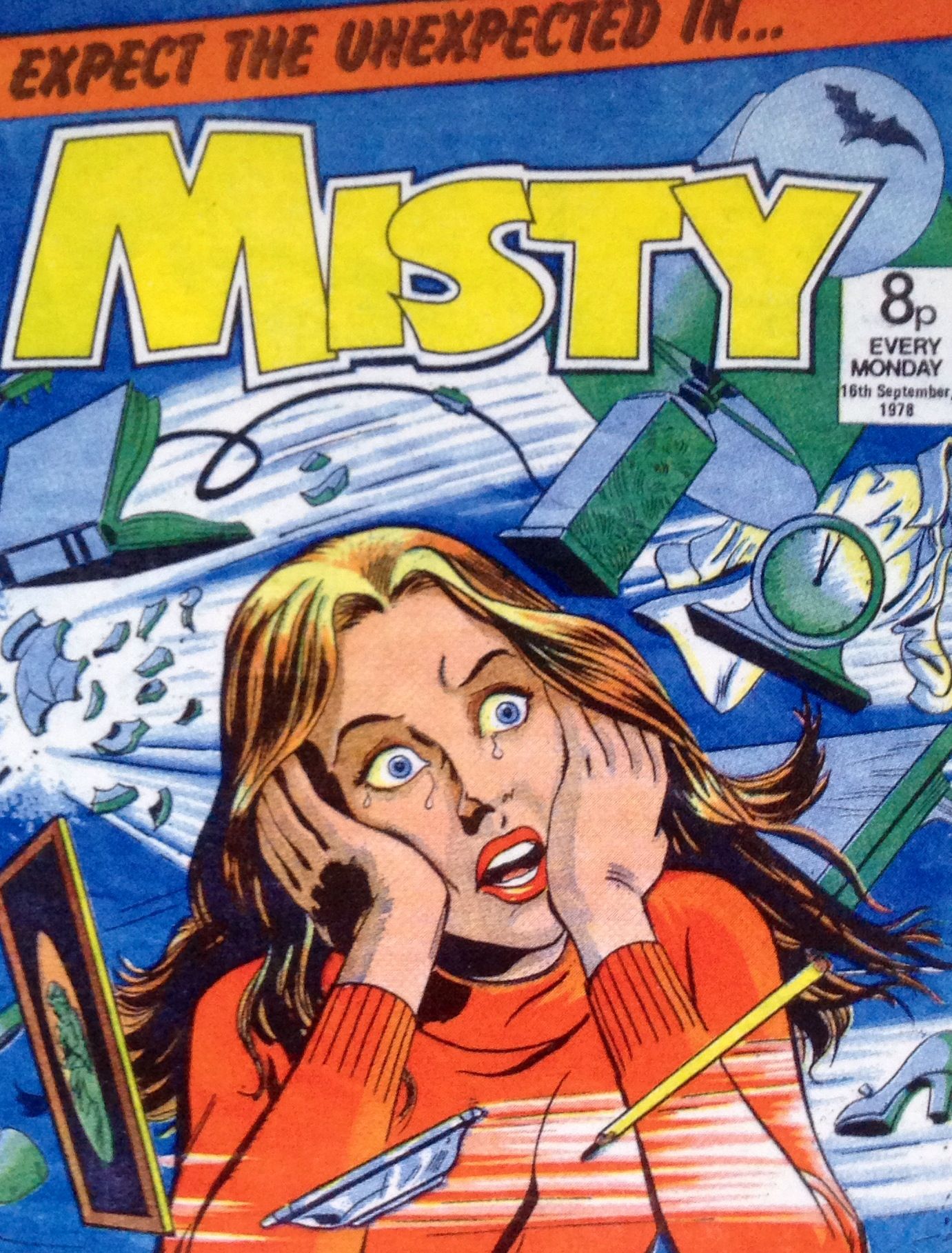

I think that the British comics industry is a fascinating example of the intersections of creativity and commerce. In the 1950s and 1960s comics dominated children’s entertainment in the UK – a 1953 study by L. Fenwick revealed that 94% of girls read comics. By the end of the 1950s there were at least fifty different titles in the UK, with more emerging in the 1960s and 1970s, and some had weekly circulations of a million or more (School Friend in the 1950s; Jackie in the 1960s). But the market collapsed in the 1970s and today The Beano and Commando are the only ones to remain in print, alongside a selection of magazines that are predominantly based around toys and merchandise. The decline of the market in the 1970s was part of a wider loss of readership that affected British comics (particularly girls’ comics) across the board. My research reveals that this had its roots in company policies, the denigration of creators and readers, economic factors, and a loss of clear direction and identity for previously distinct titles. The publisher’s corporate structure was absolutely key to the demise: a ‘cost centre’ policy meant that each weekly issue had to turn profit, not to mention a top-heavy management structure that contrasted with the small editorial teams (generally four people for each title). Creator rights were non-existent (credits did not appear in most titles) and so the talent was quick to depart for other countries or media when other options such as children’s paperback fiction opened up.

The audience was also abused – what British readers really remember about the decline is the merger strategy, known as ‘hatch match and dispatch’. When sales started to fall on an established title it would be merged with another to artificially boost the circulation figure. This would keep it alive for a time, but there was always the possibility of it ending abruptly if sales kept falling. The merger strategy led to a loss of clear identity, and readers would quickly drift from the new combined title as their favourite stories or characters appeared less or were watered down. Having invested years of time, emotion and money, readers were understandably upset when their comic ended without warning – often with serials simply unfinished, or wrapped up abruptly and unconvincingly in a single episode. For me—following critics such as Hannah Priest (2011), Spooner (2017) and Buckley (2018)—this is just another example of how certain demographics (such as young female audiences and consumers) are marginalised and disregarded socially and critically. Acknowledging their agency and allowing their tastes to shape the canons of literature and popular media gives a quite different – and much wider – picture of what a genre such as Gothic can be.

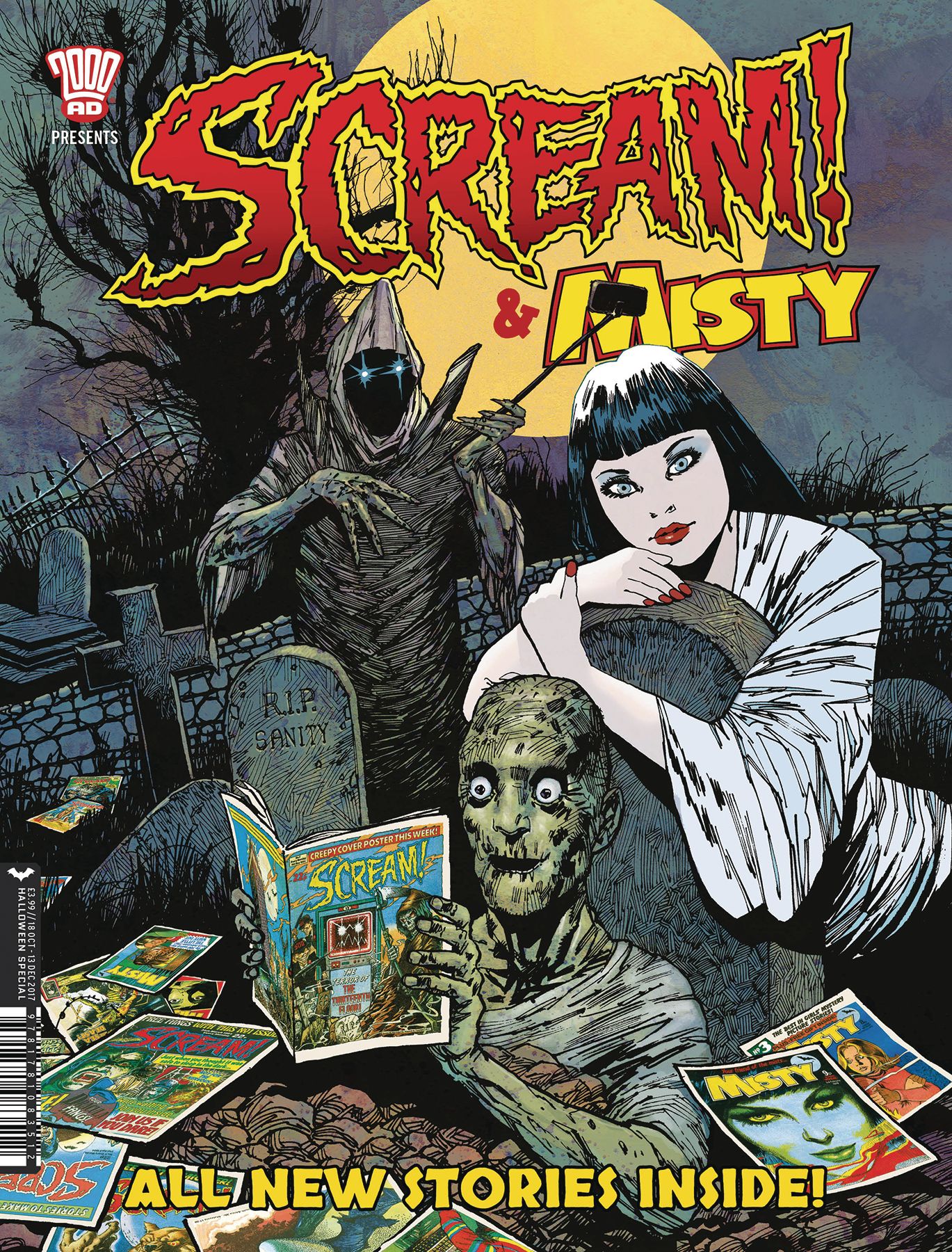

In many ways it seems that Misty "plundered" images from pop culture—the Carrie analogue is an excellent example. In some critic accounts, what Misty did with Carrie can be described as following one of the ways in which "exploitation" cinema aims to piggy-back on genre successes, like so-called "sharksploitation" fare coming off the back of Jaws (which Action analogued too with ‘Hookjaw’).

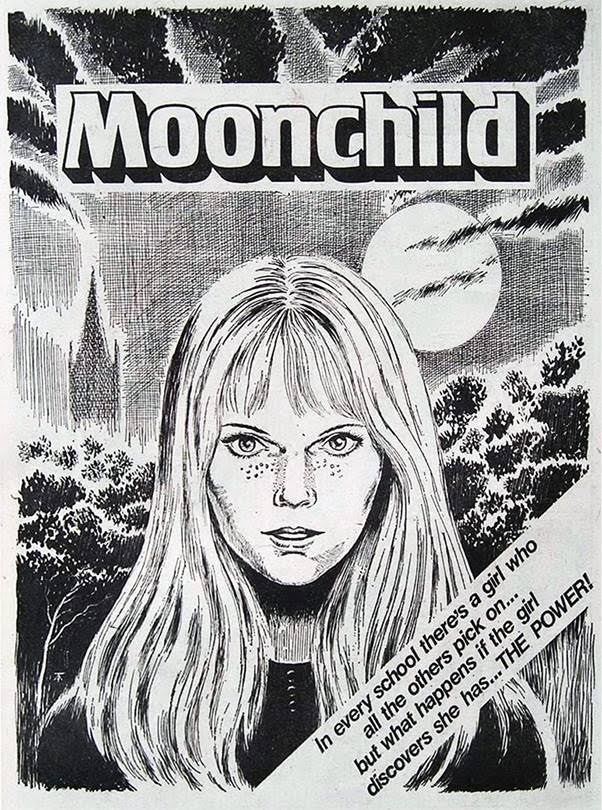

I think the exploitation model you mention is exactly what Pat Mills had in mind for Misty. His initial proposal for the comic was based around ‘Moonchild’, his adaptation of Carrie, and as you point out it's also used in other comics like Action (which he also created). But you can see this sort of thing in many titles from different comics publishers at the time – ‘Codename: Warlord’ is a James Bond rewrite (Warlord); The Dirty Dozen becomes ‘The Rat Pack’ (Battle Picture Weekly); Rollerball becomes ‘Death Game 1999’ (Action), and so on. Pat’s other major serial for Misty is a rewrite of Audrey Rose. He told me in an interview that he wanted to ‘use my 2000AD approach on a girls’ comic: big visuals and longer, more sophisticated stories with the emphasis on the supernatural and horror. My role models were Carrie and Audrey Rose, suitably modified for a younger audience.’

But that's not the comic that Misty became, largely I think due to Wilf Prigmore and Malcolm Shaw. Prigmore’s brief was to deliver a mystery comic and it is likely this was led by commercial issues. He’s said that DC Thomson’s Spellbound was never mentioned to him, but the IPC exec would definitely have wanted a title to compete with this. The back and forth between the two publishers had been going on for decades, across all genres. Eagle had dominated the boys’ market since its launch (1950), until DC Thomson brought out a number of new titles, of which Victor (1961) and Hornet (1963) had the most impact. When DC Thomson's Warlord (1974) came out it had longer stories and dramatic layouts, and IPC responded to its military themes and gritty action. They brought out Battle Picture Weekly in 1975 and the now-notorious Action in 1976, and DC Thomson then hit back with Bullet in 1976. For the girls, School Friend (1950) competed with Girl (1951), and the romance comics also battled it out as Marilyn (1955) and Valentine (1957) fought against DC Thomson’s Romeo (1957) and Jackie (1964). The next game changer was DC Thomson’s Bunty (1958), with a dramatic take on the now-stale school formula, until IPC responded by taking the genre to the next level with Tammy (1971) and Jinty (1974). These were comics filled to the brim with trauma and angst, and this was the wave of which Spellbound (1976) and Misty (1978) would become a part. So like many other British comics of the time Misty did piggyback off the industry’s successes. It owes a lot to its stablemate Tammy and also competitor titles such as Diana and Spellbound.

It also draws heavily on the surrounding atmosphere of horror in 1970s Britain. The 1970s were a strange time in the UK – uncertain politically and threatening globally – with terrible fashions, recessions and ideologies coexisting alongside great advances in technology, environmental law, and equalities. Many of the Misty stories articulate specific fears of the decade (environmental, social), and it also draws strongly on the contemporary new age witch in the character of Misty herself. Horror was also a dominant presence in British children’s media at this time (for those interested, Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence’s Scarred for Life is a brilliant encyclopaedia of the various television shows, books, movies and other fare on offer).

So horror for both adults and children was at its zenith in the 1970s, and Misty of course follows the cultural mood. A number of the Misty serials adapt contemporary horror books and films in different ways. For example, ‘End of the Line’ (Malcolm Shaw and John Richardson, #28-#42) recalls the movie Death Line (1972) where people are kidnapped by the cannibalistic descendants of a group of Victorian tube tunnel workers trapped underground. ‘The Sentinels’ (Malcolm Shaw and Mario Capaldi, #1-#12) shares its alternate history setting of Nazi-occupied Britain with It Happened Here, a 1964 British film. It perhaps also takes its title and scenario from The Sentinel (Konvitz, 1974; movie adaptation dir. Winner, 1977) in which protagonist Alison discovers her Brooklyn apartment building contains the gate to hell and that she has been chosen by God to be its guardian. Shaw’s writing often uses pre-existing texts as a jumping off point: combining a new genre (such as science fiction) or plot events (Ann’s hunt for her father) with the catalyst or backdrop of an existing text. By contrast, Mills’ rewritings more directly rework the key story elements into more juvenile forms: removing the sex, death, and gore.

Pat Mills has spoken at length about his ‘formula’ approach to British girls’ comics (see the blog posts on his Millsverse website, cited below) – where stories can often be categorised into various types. These include the Slave story (a victimised individual or group); the Cinderella story (a down-on-her luck heroine); the Friend story (the heroine’s desire for a friend); and the Mystery story (which can be as simple as ‘What’s inside the box?’). All of these categories resonate with Gothic themes (power, control, persecution, isolation, suspense). But my analysis of Misty showed that the categories are seldom clear cut and around a quarter of its stories do not fall into any of these categories. So instead I used an inductive approach: noting down similarities between stories as they emerged and creating an expanding list of common plot tropes. These included elements such as external magic; internal powers; wishes being granted; actions backfiring, and so forth. My findings were especially interesting as they revealed that the stories contained an emphasis on personal responsibility – echoing the dominant mood of 1970s horror movies and other British media such as public information films.

‘glory knight: Time Travel courier’ (June and School Friend, 1971).

Are there any other “unusual places” that you have found Gothic influences through your research in other mediums or genres?

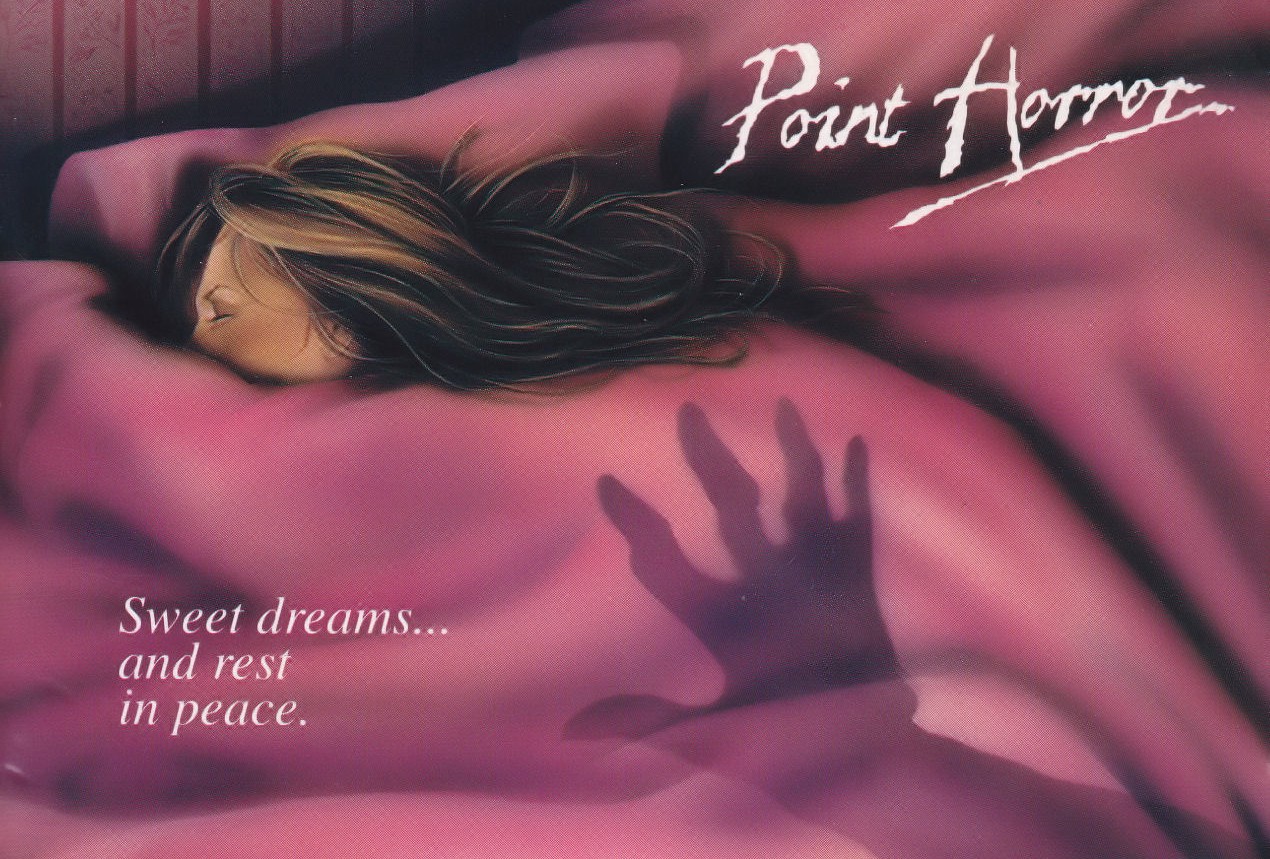

Although it might seem an odd fit, there is a clear trend for Gothic in children’s literature that critics like David Rudd (2008) and Buckley (2014) have traced back to Victorian literature. Writers such as Frances Hodgson Burnett (The Secret Garden, 1911) and Philippa Pearce (Tom’s Midnight Garden, 1958) deal in isolated protagonists encountering strange new worlds. Dark fantasy, ghost stories and alterities abound. At the cusp of the millennium imprints such as Point Horror or Goosebumps emerge. Subsequent writers such as Lemony Snicket (A Series of Unfortunate Events, 1999) and Neil Gaiman (Coraline, 2002) lead into a large chunk of literature and media for adolescent girls based around the supernatural (Buffy, Twilight, The Southern Vampire Mysteries, Once Upon a Time, The Vampire Diaries, and so on).

When I analysed Misty alongside other horror media of the 1970s and also as part of this wider trend towards Gothic in children’s literature, I found it a good fit with the large number of contemporary Gothic-themed stories for children and young adults that construct a young female reader and give her agency. Many of the most popular have clear similarities, as young female protagonists experience isolation, transformation, and Otherness during a quest for individuation. I used these findings alongside in-depth analysis of Children’s Gothic and Female Gothic to construct a definition of Gothic for Girls. I argue that this is an undertheorised subgenre, despite appearing over and over again in texts for young female readers around the cusp of the millennium. It takes place in a magical realist world, focusing on a young female protagonist who is usually isolated or trapped in some way. The narrative enacts and mediates their wakening to this and their own magical potential. Temptation and transgression are the main catalysts, creating a clear moral or lesson, as traditional fairy tale sins (greed, pride, laziness) are common sources of conflict. Personal responsibility thus becomes a key factor in negotiating the story’s traps, curses and other magical dangers, and self-control or self-acceptance a means of escape. In this way, Gothic for Girls constructs and acknowledges girlhood as an uncanny experience.

That's a very condensed version of my findings and my critical definition! – and while I can’t be sure if it will stand the test of time, I hope it helps to draw attention to other aspects of Gothic and girls beyond the superficial and sexualised. By critically analysing Misty in such detail, I’ve tried to provide evidence not only of its individual worth but also of its similarities to many other British girls’ comics. Literary scholarship – including Gothic criticism – has also often treated its privileged texts as anomalies, for example citing the genius of Radcliffe or Shelley as exceptions to the norm. Rather than framing Misty as a title of exceptional brilliance, I use it as an exemplar of the unsung significance of British comics and their creators more generally. Publishers are seeking to revitalise the comics industry today and comics studies is fast becoming its own academic discipline and thus creating its own canons (both academic and fan-based). I think that the story of Misty demonstrates that we should aim for a more inclusive approach than has been the case previously in literature, art and society.

‘Queen’s weather,’ Misty #18.

And finally, which five examples would you select that represent “the best” that Gothic comics can offer? In particular, perhaps, a Gothic for Girls?

I’m not sure I want to narrow myself to Gothic for Girls here (if that’s OK), as my wider work is more concerned with those unusual places that Gothic can be found. Instead I’ll try and pick from some different genres so I can display some of the breadth of Gothic in comics. So (bearing in mind that I’ve already mentioned Misty, Spellbound, Sandman, Preacher, Hellblazer, Creepy and Eerie!) here goes… If you’re new to comics then these are all great starting points!

From Hell (Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, 1989-1998)

It wouldn’t be a ‘best of’ list without including something from Alan Moore, and this is the obvious choice. Originally serialised in British comic Taboo, the collected edition (1999) is a work of vast scope with extensive references and appendices. Nothing like the abysmal 2001 movie, this comic is an impeccably researched retelling of the Whitechapel murders that terrorised Victorian London in 1888-91. Eddie Campbell’s art, laid out in regular grid pages, is scratchy and evocative, bringing the East End to life in all its squalor and chaos. It’s a story firmly grounded in its location and many of its settings (such as the Hawksmoor churches) can still be seen today. Alan Moore brings in cosmology, conspiracy, black magic, secret societies, time travel and more to create a work of speculative faction that will mess with your understanding of history, time, and space.

Adamtine (Hannah Berry, 2012)

Hannah Berry was recently made this year’s Comics Laureate in the UK and this is a great work from the British small press. Claustrophobic and dark, it’s about a seemingly unconnected group of people whose actions have some violent consequences. The oppressive darkness of a nighttime train journey is the catalyst and its skillfully evoked as Berry combines a sense of creeping menace with outright shock. Achieving a jump scare in a static medium like comics is no mean feat – buy a signed copy direct from the author’s website for a small extra surprise. You can also read a preview for free at http://hannahberry.co.uk/.

Locke and Key (Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez, 2008-2013)

Locke and Key is a beautifully plotted work (both spatially and narratologically) that spans many subgenres of horror and Gothic – it’s part literary ghost story, part slasher movie, part psychological thriller. It tells the story of the three Locke children, Tyler, Kinsey and Bode, who move to their ancestral home, Keyhouse, after their father is murdered. Here they discover that the house’s doors offer a range of powers when they are unlocked with certain special keys. I think it does some extremely interesting things with metaphor and space, as well as being a cracking read and one of the prettiest comics I’ve seen in a while. It’s one of the best from the American mainstream in recent years.

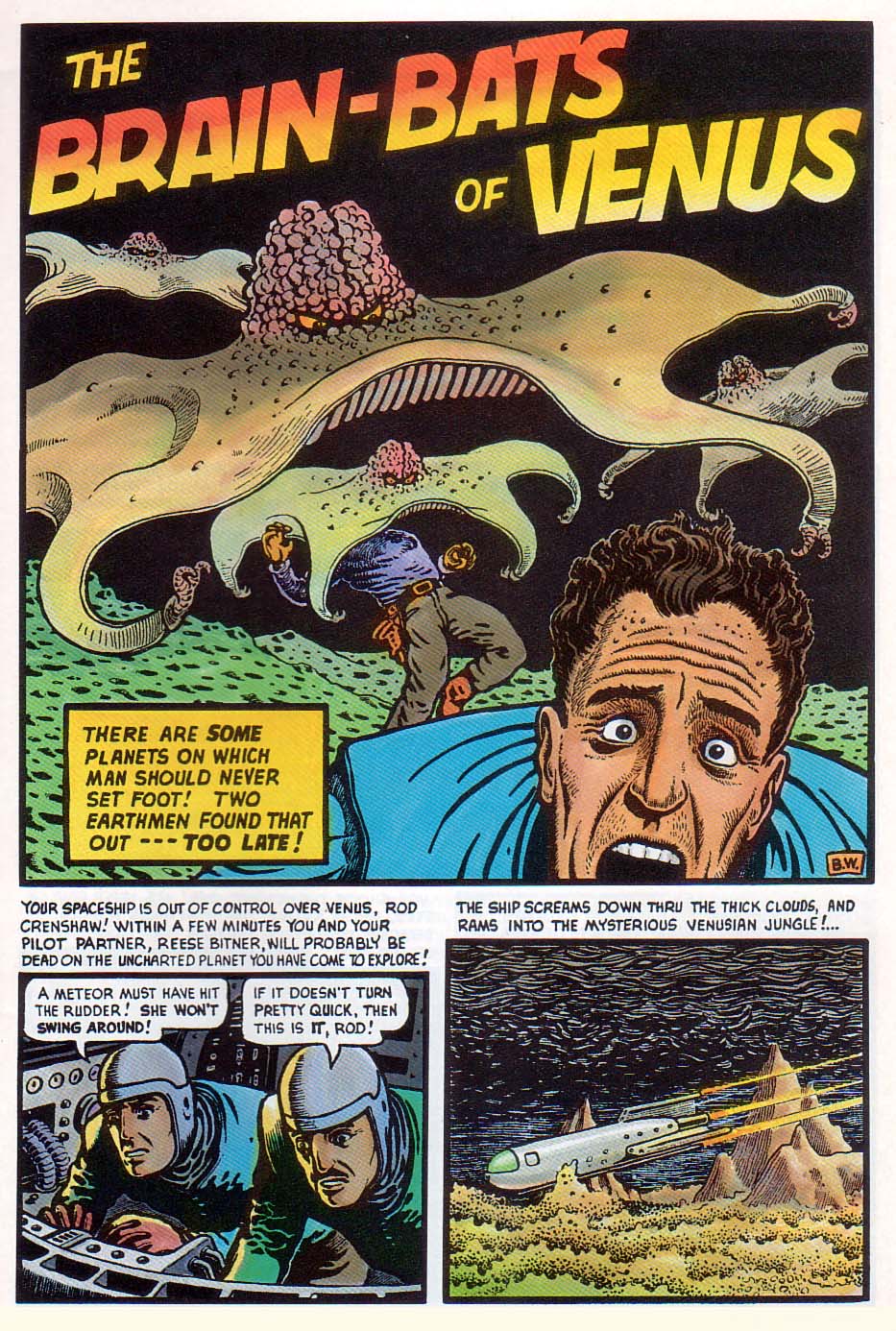

Some pre-Code American horror titles

The American horror comics that sparked the introduction of the Comics Code are classics of the genre and well worth a read. Range beyond Tales from the Crypt into EC’s other titles to find some hidden gems – Shock SuspenStories offered dark social commentary, and The Vault of Horror is just as terrifying as the crypt! Or dig into some less well-remembered titles from other publishers such as Atlas (who would become Marvel), or Harvey Comics. There are too many great stories to choose from, so can I instead recommend a visit to Steve Banes’ website

https://thehorrorsofitall.blogspot.com/?m=1. But if you force me to pick, then personally I’d say that those who search for the wonderfully titled ‘The Brain Bats of Venus’ (art by Basil Wolverton, Mister Mystery #7, 1952) will probably not leave disappointed…

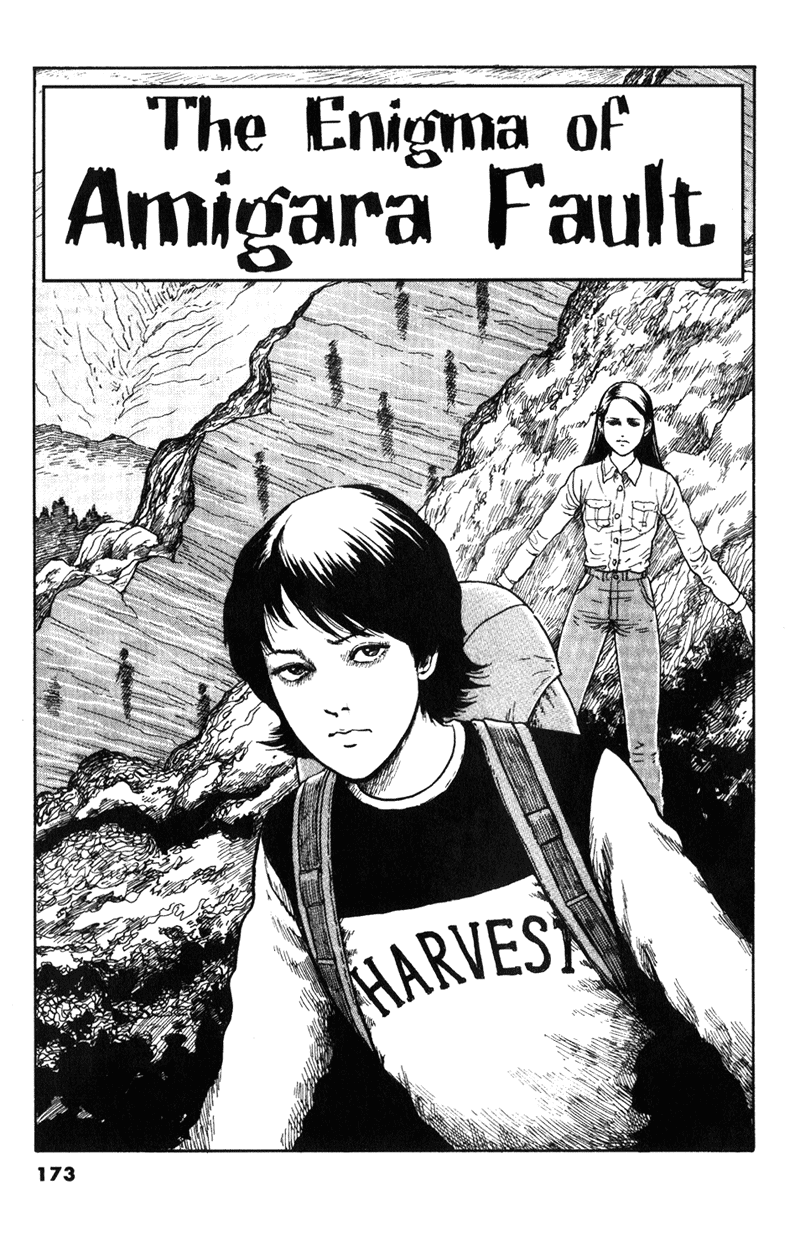

The Enigma of Amigara Fault (Junji Ito, 2003)

Junji Ito is the master of Japanese horror – in particular body horror that simultaneously tends towards the psychological and pathological. His most famous manga, Uzumaki, is about a town whose inhabitants become obsessed with spirals. It’s a bit of an epic, so instead I’ve picked this short story of his, which appeared in his horror manga Gyo (2003). It’s also a tale of obsession - and it’s available to read for free online at https://m.imgur.com/gallery/ZNSaq. If you like it then do check out his other work – Tomie is another great starting point.

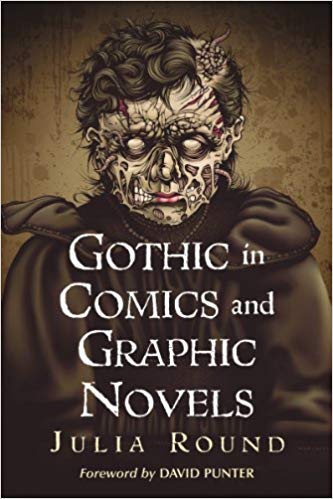

Julia Round is a Principal Lecturer in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, UK. She is one of the editors of Studies in Comics journal (Intellect Books) and a co-organiser of the annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference (IGNCC). Her first book was Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (McFarland, 2014), followed by the edited collection Real Lives, Celebrity Stories (Bloomsbury, 2014). In 2015 she received the Inge Award for Comics Scholarship for her research, which focuses on Gothic, comics, and children’s literature. She has recently completed two AHRC-funded studies examining how digital transformations affect young people's reading. Her new book Misty and Gothic for Girls in British Comics (forthcoming from UP Mississippi, 2019) examines the presence of Gothic themes and aesthetics in children’s comics, and is accompanied by a searchable database of all the stories (with summaries, previously unknown creator credits, and origins), available at her website www.juliaround.com.