Popular Religion and Participatory Culture Conversation (Round 7): Nabil Echchaibi, Yomna Elsayed and Kayla R. Wheeler (Part 2)

/Yomna:

Nabil, I really enjoyed how you historicized the rise of popular religion in the Middle East and connected it with the events of 9/11. It was particularly refreshing to see you contextualize the Khaled phenomenon and recognize it as an effort to rearticulate religious traditions. This is an essential point.

While my personal experience and that of the youth in the digital spaces I study convey a general disenchantment with the figure of Amr Khaled, as a form of popular religion, this does not discount the fervor with which his phenomenon was received. To me, this betrayed a thirst for reconnection with tradition, and a quest for a genealogy of the modern Muslim self.

Khaled only happened to scratch the surface of this underlying need. His mix of religion and entrepreneurship as you describe it, however, did not hold up to the depth of this need and the test of the Arab Spring. Likewise the self-help genre (Tanmiyya Bashareyya) that was coincident and intimately interwoven with Amr Khaled’s message did not withstand the Arab Spring developments. A disillusionment in this genre surfaced in the form of sarcastic memes and parody videos that took aim at Khaled and not surprisingly this same genre within which his lessons predominantly fell. To this end, I agree with Donald Hall when he argues in Subjectivity that self-help messages tend to fall within the interests of laissez-fairepolitical interests, absolving the government of their role in social welfare.

To me, utilizing sarcasm in critiques of religious figures, was a tell-tale sign that a relationship was transforming; it signaled that the religious top-down communication has been fragmented and replaced with a two-way one, whereby youth could critique the credibility and the message of the speaker, even if it was religiously framed. Perhaps the very fact that Khaled was not religiously trained, provided the youth with the license to venture into religious negotiation.

Many theorists understandably refuse to describe the Arab Spring as a movement and constraint it to the bounds of a temporally-bound uprising without consequence, especially with the situation in Egypt becoming more draconian than before. But that would be true, if we were to restrict ourselves to the political reading of events. Those uprisings launched a wave and a movement whereby many social practices and beliefs, from personal relationships to religious teachings were being recalibrated (at least in the minds of young adults) based on the ideals of the Arab Spring and its demands for “’Eish, Horreya, ‘Adala Egtima’ya: Bread, Freedom, and Social Justice.”

However, as many of the researchers of this highly misrepresented, and misunderstood MENA region, I always run the risk of being misquoted in an attempt to reinforce orientalist binaries—East/West, Civil/Barbarian, Modern/Traditional—that we as, postcolonial scholars, constantly fight in our work. I worry that those critiques may be read as a sign of religious reformations that contest premises not execution, mirroring the Christian reformation, thereby canceling the agency and particularity of Muslim subjects and societies. This concern is further complicated by the fact that Muslim societies, like any society, struggle with their own marginalization of racial, and religious minorities. This is why a critique from within, such as Kayla’s is ever more pressing, where we criticize Western hegemony all while acknowledging and critiquing our own.

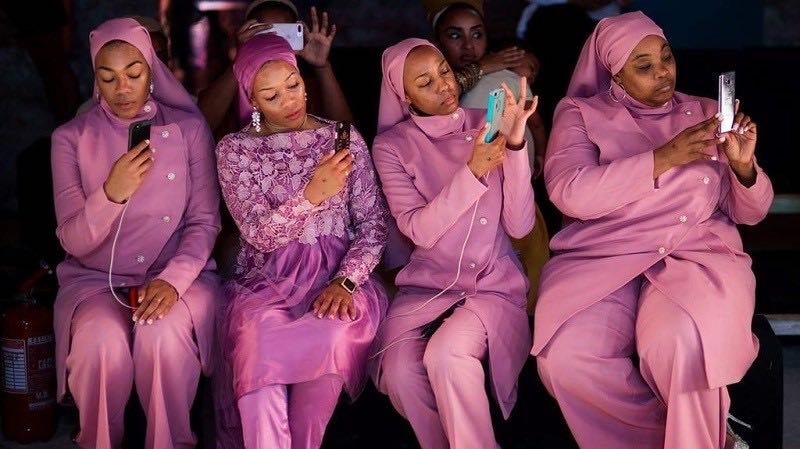

Despite the fact that we study Muslims in different parts of the world, we make surprisingly similar observations. Young Muslim Adults, in both the US and the MENA region, are challenging forms and expressions of what they consider a bygone nationalistic era that does not reflect their current aspirations nor challenges. Our research continues to show, how arts, culture and fashion are utilized as means for challenging the long established political, cultural and religious institutions. It is quite fascinating to even witness this shift among American Muslim descendant from Arab-speaking parents, and how they are gravitating towards, as well as adopting, Black Muslims’ fashion trends and expressions. On one hand, it could be their way of asserting their American identity by embracing the fashion styles of Black Muslims whose history in the US dates back to the antebellum era. On the other hand, it could also be their way of carving out a new “cool” identity, as Kayla describes it, that is expressively different in essence and appearance from that of their parents.

With continuously maturing sensibilities flourishing in digital participatory cultures, are we witnessing a demise of the traditional religious sermon: A process of disentangling religion—I would not say from politics—but from dogmatic authority? Is the interplay of Arab Spring agency, Black Muslim women self-assertion and digital technologies powerful enough to reorganize centuries-old ways of accreditation and preaching? What I see us doing in our research is analyzing this slow cultural build-up (towards a movement, an uprising, or a revolution, albeit slow one), by studying the more main-stream/less famous border-line professional/border-line activists who are able to translate the language of activism and sometimes religion to that of subject classes through arts, culture, and fashion.

Nabil:

Yomna, you raise a critical point about the disenchantment with the Amr Khaled phenomenon. I’d join you in your assessment and state even further that his form of popular preaching has been substantively vacuous in terms of its engagement with tradition. Khaled’s popularity was due in large measure to his success in re-socializing Islam based on a neoliberal program of consumption and individual emancipation, particularly among the middle and upper class of Egypt and other Arab countries. I would also say that his waning popularity today is arguably a good proof of this disillusionment in substance and his inability to forge a more compelling Islamic ethos that is not overly determined by neoliberal logics and practices. Just to be clear, Amr Khaled has never been an agent of Islamic reform, nor has he been an advocate for a critical engagement with Islam. My point, however, is that various accounts and analyses of Amr Khaled and other popular preachers not only in Egypt, but also in Turkey, Malaysia, and Indonesia, have focused exclusively on the novelty of this genre of popular religion and its striking similarities with evangelical Christianity that they miss any connection with a long-standing tradition in Islam of non-official and unsanctioned forms of preaching which have left indelible marks on how Muslims practice and experience their faith today. This oversight can devalue Muslims’ ability to engage, contest and rework the pull of tradition and the pressures of modernity and how Muslims deal with various epistemologies of and innovations in religious mediation.

It bears repeating that Khaled’s intervention is indeed not about critical reform, but his brand of consumer Islam and visual devotional programming has recast faith as an engine of social mobility and self-improvement which directly competes both with state power and religious opposition groups like the Muslim Brotherhood or mainstream religious authorities like the clerics of Al-Azhar. It was not a coincidence when the Mubarak regime banned him from preaching in public. Khaled’s realignment of Islam with consumer culture, self-help, and social mobilization was a political affront and cannot be discounted because it also focused the nexus of social action on the self and the need to reform the Muslim individual first in order to enact a larger program of social change.

This individualization of Islam and the privatization of faith allow for an intensification and expansion of the political beyond the habitual spaces of political activism as in political parties, voting, large scale protests, etc. There are important arguments against the risks and limitations of deploying individual solutions to structural problems, but there are also compelling theoretical reasons to focus on the complex intersections of personal and collective identity in Muslim lived experiences without reducing this phenomenon to neoliberal logics of individualism and consumerism. The work of Turkish sociologist Nilüfer Göle on this emerging manifestation of Islam through the lens of identity and difference is exceedingly instructive in this regard.

This is why the work Kayla is doing on historicizing Islamic fashion as a fluid bodily ritual is so important now. The concept of “cool Islam” is a complex category that reflects both the specific lived reality of Muslims in various locations, but it also marks an important contestation of dominant and normative standards of modesty, agency, and liberty. Muslim fashion and other artifacts of material culture foreground an alternative public imaginary of the interaction between beauty, modesty and public space. This new contested visibility of Muslim identity in non-Muslim majority contexts complicates not only the performative nature of piety, but it also challenges the received definitions of the religious and the ethnic in secular societies. In the context of fashion and black Muslims in the anthropological work of Kayla, blackness and Islam are equally interrogated in terms of how they inspire the cultural production of black Muslim women while resisting hegemonic forms and narratives of proper piety and modesty within Sunni Islam. I also appreciate the historical sensibility of this research as it analyzes black Muslim fashion in the context of the American Muslim black experience which cannot be simply reduced to its connections with Islam in the Middle East or other Muslim-majority societies.

It is refreshing to see how our research complicates the study of Islam in various geographical locations and based on different cultural experiences of Muslims around the world. I would agree that we are arguably witnessing the decoupling of Islam from its old moorings in dogmatic authority, causing significant disruptions in how Muslims re-imagine the symbols, values, and codes that inform their identities. But this kind of Muslim self-fashioning aided by elaborate circulation networks of digital communication cannot be studied only in terms of its difference and contestation of dominant secular arrangements. A question I come back to quite often now is: do we study Islam and Muslims simply to underscore this difference and intensify some sort of Muslim distinction, an alternative modernity of sorts? Or is our work still invested in questions of the universal, albeit a more lateral form of the universal?

Kayla:

Yomna and Nabil, I really enjoyed learning more about your research. I agree, we all have a lot in common. Identity production through consumption seems to be central to all our research, whether it is buying modest clothes, spreading memes, or watching sermons online. What I love the most about the study of popular religion is that it highlights youth’s voices, who are often pushed to the margins both in scholarship and everyday life. Yomna, this is something you introduce towards the very end of your post, when you talked about digital spaces helping youth rediscover what brings them together based on their intersecting identities. However, I wonder how by focusing on people who have the time, money, and other resources to engage with media, we might be ignoring even more marginalized groups, like the poor and elderly. Who is the Amr Khaled for Egyptians living outside of urban areas, who might not have the same rates of access to a steady Internet connection or have different relationships to religious authority? In what ways does place dictate how we consume religion?

I am also interested in how a focus on popular religion can reveal transnational dialogue. Media allows people in the diaspora to connect to struggles back at home, but to also introduce them to people dealing with similar struggles. I’m thinking of how Khaled M and El Général cited Tupac as a major influence for their music produced during the Arab Spring or how Palestinians sent Ferguson activists advice on how to deal with tear gas. On the flipside, this mass circulation of art, culture, and fashion allows for local practices to be appropriated and decontextualized. I agree with you, Yomna, Arab American youth are using Black Muslim culture to claim their American identity. I’ve watched non-Black Muslims monetize Black Muslim culture without making space for Black Muslims and at times, embrace anti-Blackness. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer’s book Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United Statesdoes a great job of breaking down non-Black Muslims’ relationship to Blackness.

I appreciate how you both have placed Amr Khaled within the history of sermonizing in Islam, rather than solely comparing his trajectory to evangelical Christian ministers. Religious Studies, as a field, has not developed a common language for discussing non-Christian practices/beliefs/rituals/traditions without making comparisons to Christianity. I often wonder how much different our conversations would be if Religious Studies was able to rid itself of its Protestant influence and we, as scholars, were not so concerned with the Christian gaze. Yomna, I can relate to your concerns about your work being misused and weaponized. I grapple with theses tensions a lot in my work because covered women are hypervisible in the media and in scholarly writings on Islam and they experience harassment and violence due to anti-Muslim sentiment at disproportionate rates in their everyday lives. I worry about how my work may contribute to the fetishization of covered Muslim women, reducing them to walking hangers, while simultaneously erasing women who don’t cover. Nabil, do you think that as mainstream media in the U.S. has begun to present more varied depictions of Muslims (not just the dangerous Brown man and oppressed Brown woman) that it has gotten easier for scholars of Islam to just do their work without constantly worrying about how it might be mis/used?

Nabil writes that we must ask ourselves “Who do we focus on when we label our research as work on Islam?” I would add to that question by asking, who are we including in our definitions of “Muslim”? I hope our focus on popular religion provides us with an opportunity to center non-Sunni Muslim voices, like members of the Nation of Islam, who have been engaged in political activism and reimagining religious authority since its creation. When I was reading both of your introductions, I kept thinking about Elijah Muhammad and Louis Farrakhan and how they have both used media (radio, journals, social media) to share their message of self-improvement. How do they, and other non-Sunni Muslims outside of the MENA region, fit into your genealogies and analyses? How might a deeper engagement with critical race theory shift our work? What does Islamopolitanism look like when Black people (on the African continent or in the Diaspora) are at the center of our analyses? If you don’t already engage with their work, I think Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, Sylvia Chan-Malik, and Jamillah Karim’s would be especially helpful. How can our explorations of popular religion help us to redefine or reimagine our citational politics?

I am excited to see how your projects continue to develop and look forward to continuing these conversations!

Yomna Elsayed holds a PhD in communication from the University of Southern California. In her research, she examines the interplay of popular culture, social change and cultural resistance. Her dissertation examined how popular culture mechanisms, such as humor, music and creative digital arts, can be utilized tosustain social movements all while facilitating dialogue at times of ideological polarization and state repression.

Nabil Echchaibi is chair of the department of media studies and associate director of the Center for Media, Religion and Culture at the University of Colorado Boulder. His research and teaching interests include religion, popular culture, postcolonial and decolonial theory, and Islamic modernity. His work has appeared in various journals and book volumes. His opinion columns have been published in the Guardian, Forbes Magazine,Salon, Al Jazeera, the Huffington Post, Religion Dispatches and Open Democracy.

Kayla Renée Wheeler is an Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Digital Studies at Grand Valley State University. Currently, she is writing a book on contemporary Black Muslim dress practices in the United States. The book explores how, for Black Muslim women, fashion acts a site of intrareligious and intra-racial dialogue over what it means to be Black, Muslim, and woman in the United States. She is the curator of the Black Islam Syllabus, which highlights the histories and contributions of Black Muslims. She is also the author of Mapping Malcolm’s Boston: Exploring the City that Made Malcolm X, which traces Malcolm X’s life in Boston from 1940 to 1953.