UK Underground Comix: Ar:Zak, the Birmingham Arts Lab, and Streetcomix #4 (1 of 3) by Maggie Gray

/Figure 1. Streetcomix #4 November 1977, Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press. Cover art © Pete Wingham. Streetcomix #5 March 1978, Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press. Cover art © Hunt Emerson

A chance encounter with the UK underground

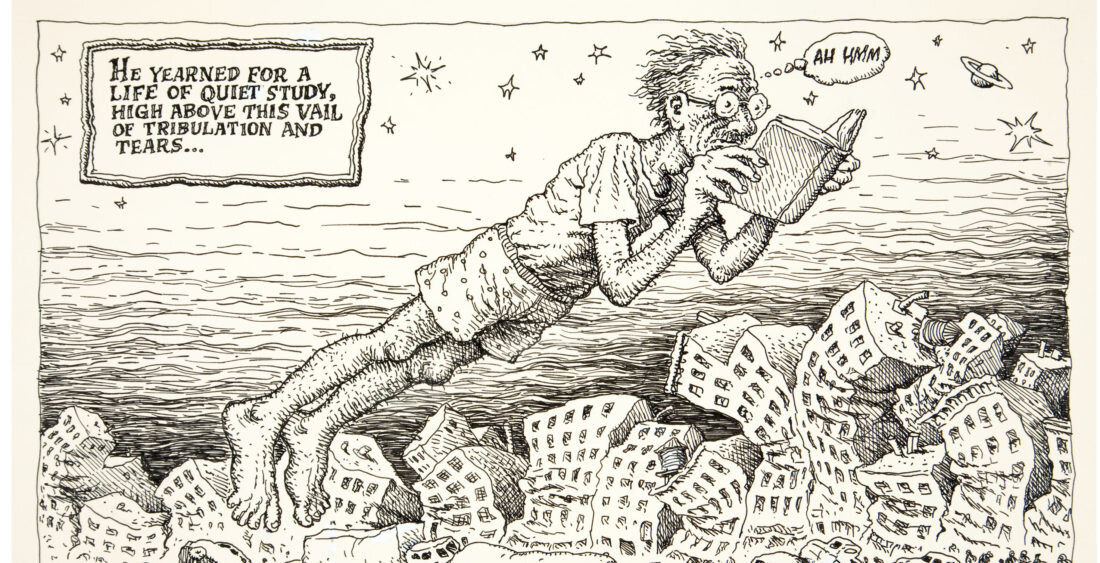

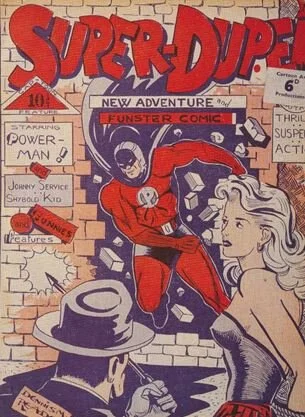

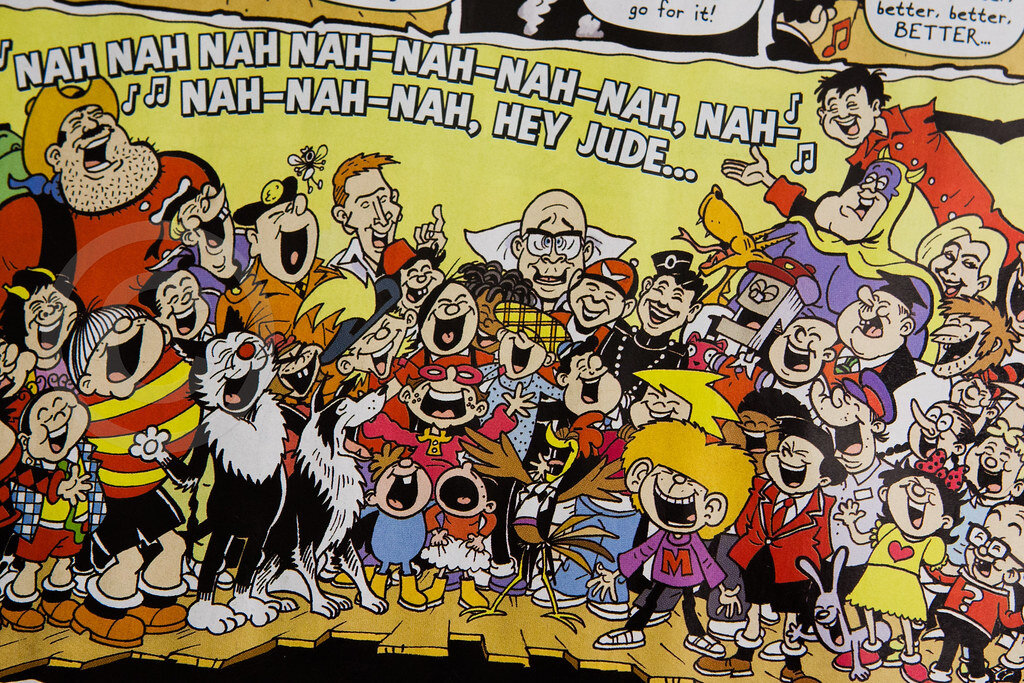

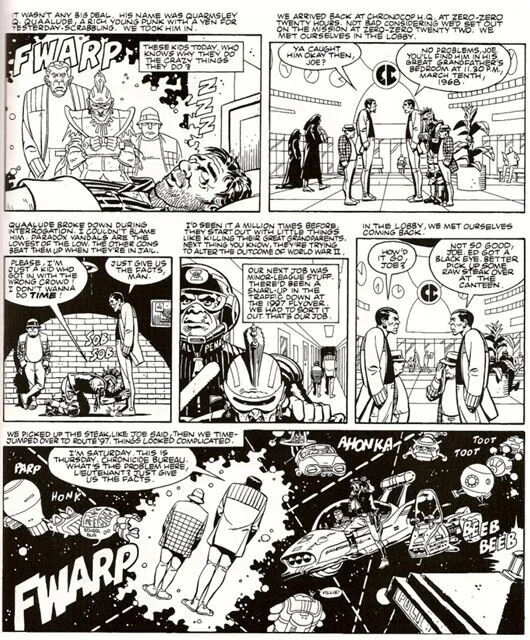

I first came across Streetcomix in 2006 at the London Comic Mart, which used to take place in the Royal National Hotel, just around the corner from University College London where I was doing my PhD. Although London Comic Mart mostly focuses on U.S. comics and collectables, you can also pick up the odd British title, and I was hunting for copies of Warrior, a later UK anthology of the early-to-mid-1980s in which several well-known strips written by Alan Moore (‘V for Vendetta’, ‘Marvelman’ and ‘The Bojeffries Saga’) were first serialised. Rifling through the boxes I was taken aback by the intense saturated colour cover of Streetcomix #4, promptly followed by Hunt Emerson’s striking issue #5 artwork, with its luminescent bugs threatening to scramble off the page onto my hands (Fig. 1). These comics had recognisable underground markers (‘-ix’ not ‘-ics’, poking fun at cops), and a dose of late 1970s punk attitude (brash, graffiti-like typography and lurid colour), but they were also quite lush material objects, with full back cover illustrations, high production values and decent quality paper stock.

My focus at the time had been on Warrior as a ‘ground-level’ indie comic, attempting to realise the artistic freedom and creator’s rights of the underground while competing via newsagent distribution with mainstream titles like 2000AD. But Streetcomix, the Ar:Zak imprint that produced it, and the Birmingham Arts Lab where Ar:Zak was based, grew increasingly relevant to my research as I became more and more interested in Moore’s earliest work for underground anthologies, alternative papers and the music press. This space of comics production carved out in Birmingham seemed to be a fulcrum of underground and alternative comics in Britain in the 1970s, bridging those scenes in ways that blurred the borders between them, and sitting at the centre at some of their core debates and developments (notably confrontations over sexism and the coalescence of a UK women’s comics movement). And Ar:Zak equally appeared to be deeply entwined in the same broader oppositional cultural formations, particularly the arts lab and alternative press movements, that had such a crucial impact on Moore and his creative practice.

Underground and Alternative in UK comics scholarship

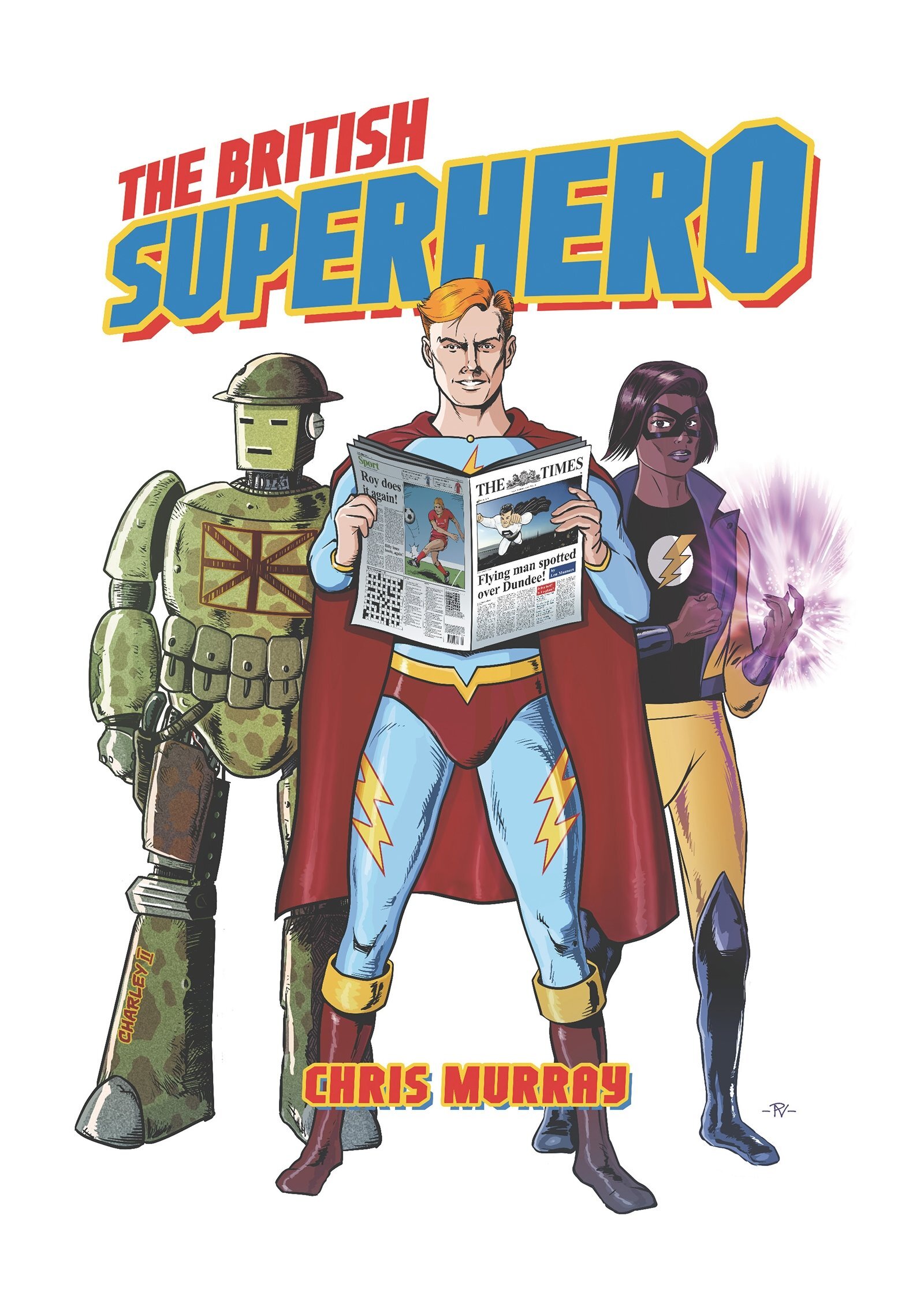

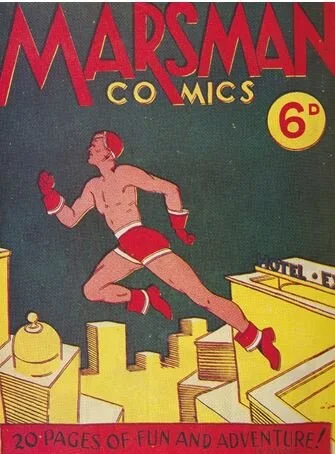

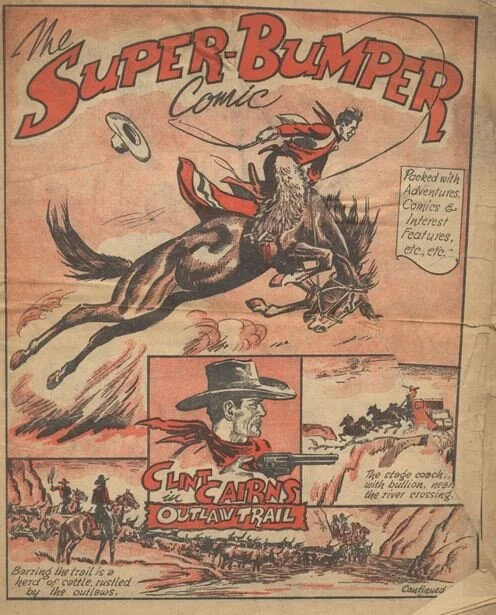

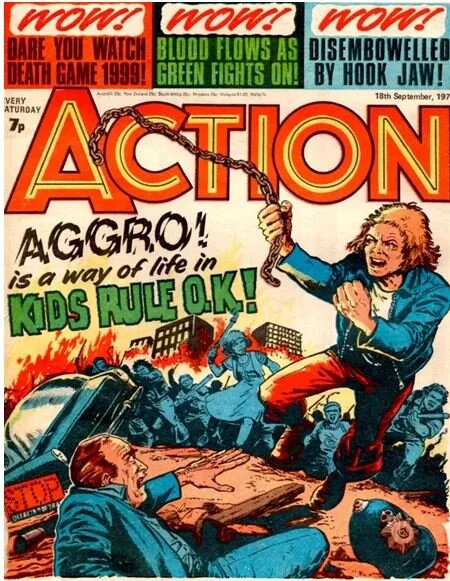

Not much has been written about Ar:Zak, partly due to the fact that not much has been written about UK underground and alternative comics in general. In the historical narrative that does exist, most notably David Huxley’s Nasty Tales: Sex, Drugs, Rock’n’Roll and Violence in the British Underground - still the only academic book dedicated specifically to the subject - British titles are divided into two waves: the first underground, the second alternative. The first wave, catalysed by Robert Crumb’s Zap, spanned the late ‘60s to the mid ‘70s and was led by publications like Cyclops, Nasty Tales and COzmic Comics, spun out of hippie underground papers IT and Oz. This wave coincides most clearly with the chronology of U.S. comix as charted by Patrick Rosenkranz (2002) and Mark Estren (1987), and was impacted by similar issues of censorship (with police raids on publishers and high profile obscenity cases like the Nasty Tales trial), escalating costs in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis, and a wider waning of the counterculture. The second wave saw the sex, drugs and anti-authoritarian politics give way in late ‘70s and early ‘80s titles like Near Myths, Graphixus and Pssst! to greater concern with production quality, stylistic experimentation, narrative complexity and/or fantasy, horror and science-fiction themes, more in the vein of artistically ambitious European comics like Métal Hurlant or À Suivre. Distribution through hippie headshop networks was superseded by the emergence of specialist comic book shops, and publishers were more professionalised and market-minded.

However, as Huxley acknowledges, the contours of these waves are somewhat hazy, and it is difficult to situate Ar:Zak squarely in one or the other. Huxley positions Brainstorm Comix, produced 1975-77 by headshop owner Lee Harris’ Alchemy Publications and prominently featuring Bryan Talbot’s work, as marking ‘the death throes of the underground movement’ in the UK (2001, p. 47). Yet others, like Roger Sabin (1993; 1996), situate it, alongside Streetcomix, as part of a partial, more regionally-dispersed revival of the UK underground in the mid-to-late-1970s, which maintained the counterculture’s ethos and organisational forms while registering the impact of punk.

Part of the challenge comes from Ar:Zak’s relative longevity, running from 1974/5 (when COzmic Comics was still going) into the early ‘80s (when Warrior was being hatched). But an inescapable factor is its foundation in the Birmingham Arts Lab, established as part of the counterculture’s autonomous infrastructure, which fought to maintain an experimental, collective and participatory approach to cultural production throughout its own comparatively extended lifespan from 1968 to 1982. As the UK’s longest running lab it engaged with the social and cultural movements emerging out of the hippie underground, above all the alternative press and community arts movements, which extended and developed many of its core principles in more decentred, networked, regional and local contexts.

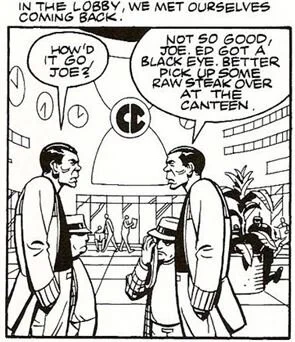

The way Ar:Zak bridged the first wave of underground comix and later, more localised DIY comics publishing; its significance in sustaining an emerging alternative comics movement; and how that was contingent on its roots in the Arts Lab as a countercultural space; can all be read in those issues of Streetcomix I stumbled across at the London mart. And because Ar:Zak’s importance to British comics lies less in any one strip or artist featured than its overall role as publisher, printer, and coordinator, its significance can be most clearly discerned by looking at what Jan Baetens and Pascal Lefèvre (2014) call their ‘perigraphy’ - front and back matter, colophons, editorials, advertising, etc. Therefore this article will explore the perigraphic features of Streetcomix #4.

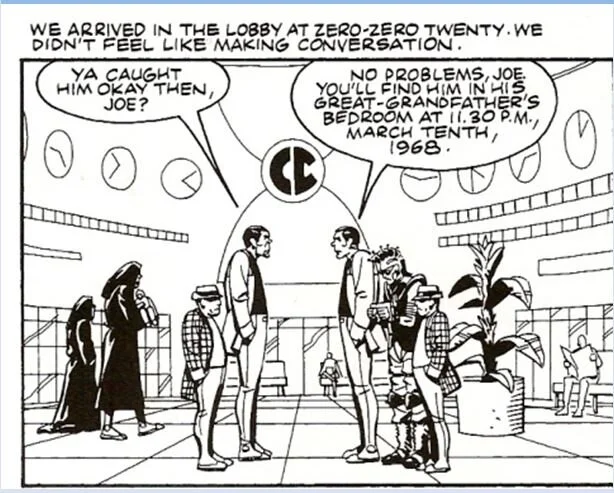

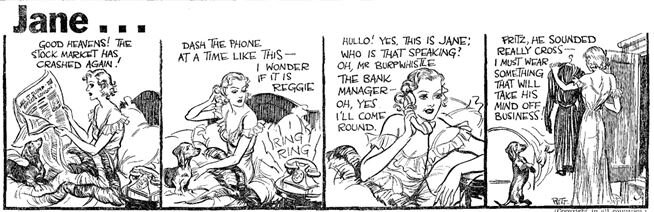

Figure 2. Colophon Streetcomix #4, p.3. © Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press

The colophon on the title page of Streetcomix #4 (Fig 2.) notes it was ‘Published, Designed and Printed by AR:ZAK, The Arts Lab Press’. This immediately tells us something crucial about Ar:Zak – they printed their comics themselves. And this was possible because the Birmingham Arts Lab ran its own press. It additionally tells us that they addressed readers as potential contributors and ascribed copyright to creators, suggesting a less exploitative, more participatory and inclusive approach than the mainstream comics industry.

Maggie Gray lectures in Critical & Historical Studies at Kingston School of Art, Kingston University. Her latest book is Alan Moore, Out from the Underground: Cartooning, Performance and Dissent, Palgrave (2017). She is a member of the Comics & Performance Network and CoRH!, the Comics Research Hub. With Nick White and John Miers she co-runs Kingston School of Art Comic Club.