How Do You Like It So Far?: What Is a Human with James Paul Gee (Part One)

/If you have not been listening to our How Do You Like It So Far? podcast this season, you have missed a series of enlightening conversations about, among other things, how news and science fiction have helped us to better understand what makes us human and how we relate to the natural world. I wanted to flag these timely episodes for my readers by sharing transcripts of two key installments.

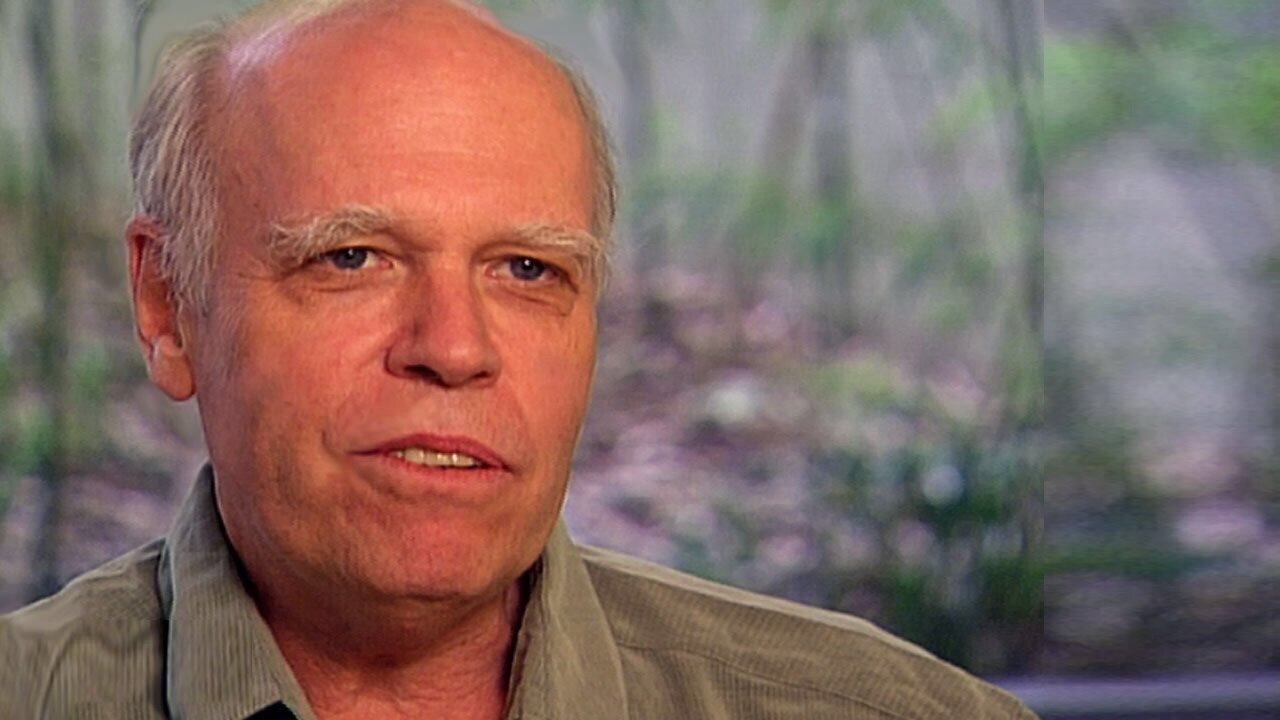

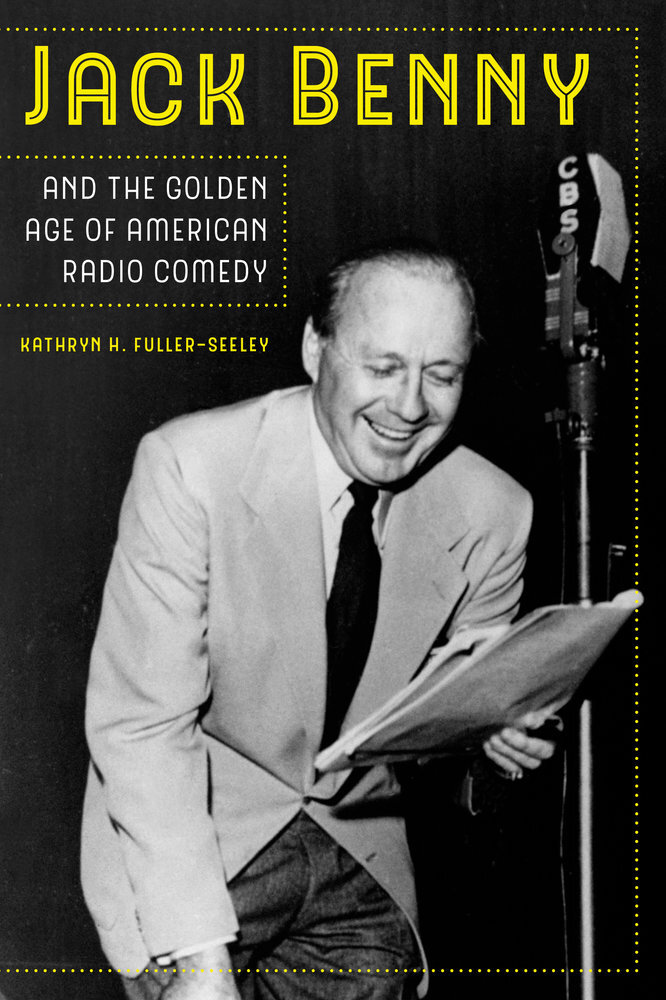

The first features James Paul Gee, an old friend, an important educational researcher and theorist who made a strong case for what educators could learn from video game designers. He talked with us about his most recent and (he claims) final book, What Is a Human?, a work strongly influenced by his retirement to a farm in Arizona and the observations he has made about animal intelligence. You can find the podcast episode here. If you want to listen to more of our episodes, you can find them at our homepage.

James Paul Gee:Humans are not motivated by truth. Period. They're motivated by comfort, but comfort isn't trivial to them. It means you've got to assuage my fear of death, my finitude, my fear that I don't belong, my fear that I'm unsafe. You've got to assuage that. Anything that will assuage that is very attractive to human beings. Now, that doesn't mean truth isn't attractive. It means you got to make it attractive. The biggest problem we have is the bad guys are really, really good at making up comfort stories that aren't true, but we, and I know it's not easy, but we should be making up comfort stories that are true to show people that truth can be comforting.

Colin Maclay:Hello, and welcome How Do You Like It So Far, a podcast about popular culture and our changing world. I'm Colin Maclay.

Henry Jenkins: And I'm Henry Jenkins. We are joined today by James Paul Gee who Wikipedia describes as a retired American researcher who worked in psycholinguistics, discourse analysis, sociolinguistics, bilingual education and new literacy studies, and as this conversation here today will suggest he's also now actively interested in animal intelligence, evolutionary biology, and essentially what makes us human. I knew him as a thinking partner for 15 years on the space of digital media and learning where we did a number of different appearances together, recently wrote a piece, in dialogue with each other. Today he's going to talk about his new book What Is a Human? And he has fascinating things to say, not only about humans, but animals. Welcome to the show, Jim, it's been a while since we've done a conversation together, but it's fun to be back together.

JPG: Yes indeed.

HJ: Your book is called What is Human? So let's cut to the chase, what is human?

JPG: What Is a Human? Yes, let's cut to the chase. Now, of course, the whole book is about it. But if I was going to put it in a very short way; humans are self domesticated, herd animals who hear voices. That is what they are. It's very interesting how they got there. What is interesting is that today a body of literature is coming out from many different fields, evolutionary biology and neuroscience and anthropological work, all sorts of work that is throwing great light on not just what humans are, but what animals are. This work is exciting, but disappointing in the way that anybody who reads it says, "First of all, we're finding out the humans aren't the least bit like what we thought they were, but then we were wrong about all other animals too." One message is, the other animals are a lot smarter than you thought, and you are a lot stupider than you thought.

JPG: Now, what do I mean by itself, domesticated, herd animal hearing voices. Well, this came out of an evolutionary set of changes that interacted. They didn't happen linearly. We domesticate animals, and the properties, by breeding them. Domesticated animals have certain properties, both in their brains and genes and body, that you could tell they've been domesticated - if a Martian came down, he'd say, "Well, somebody domesticated these guys." Trouble is, who did it? Well, we did it. We did it to ourselves. The way we did it was very, very consequential. In most animals of art that we came from, the primates, they can only really live in fairly small groups. That's because they cannot tolerate strangers, and because they settle their issues through strength, through reactive anger, immediately getting angry. The bullies are the bosses, right? They've worked it out in an interesting way. Some of them like baboons have so much stress in their systems that basically they're in misery, but they survive. That's all evolution cares about.

JPG: Now, some point in human history, very early, probably before homo-sapiens humans got the beginning of an ability to time travel, that is to think in their heads of a different time and a different place, and to begin to read the minds of others. Then eventually they're... It didn't start full blown, but they got that. One of the things they discovered when they got that is; well, a bully isn't always going to win. If a small group of weaklings get together and use this planning function, as a stealth function, as a function to get ready, they can always beat the bully. What that did is, through human history, it eradicated, just normal evolutionary terms, highly aggressive males that lash out, and it put a premium on collaborative planning ahead of time.

JPG: In the beginning, this was good because hunting gatherer groups lived in a fairly egalitarian way and bullies just were excluded, either thrown out or killed. This planning function worked pretty well, but you were still a creature that lived at most with 100 other people. You had a happy little camper group. But this mental power readily, by again, good evolutionary grounds, could go out of control because it's the same power that allows you to lie, allows you to see, allows you to think; "Is this true or not? Is that person telling the truth or not?" There is a fair amount of literature that learning to lie fuel the human brain. It's certainly built this planning function. Think about it.

JPG: Any creature that's got the capacity to lie, some of the primates have it already, is going to be heavily advantaged in an evolutionary race. The only way you're going to defend yourself is get better at detecting lies. Then the liars are going to have to get better and the detectors are going to get better. It's a race. Then the best liar biases. The best liar is a self deceiver, one who believes his own lies. This ability to create stories, fictions, lies to be able to manipulate others has taken the form in humans. It has this form in sperm whales as well, by the way, of identity signals. Humans are herd animals, but they're herd animals that are not always subject to aggression because they could be controlled by planning.

JPG: But that planning, in the best way to control them, is to send signals that we are us and therefore safe, and you are them and therefore not safe. Humans took identity signals just way out of all control, our dialects are identity signals. That allowed us to be able to live in groups the size of nations, because we have identity signals that are different levels. For example, chimpanzees could never eat in a restaurant with strangers, and humans do it all the time. But they're not strangers because they're sending you their identity signals that they're safe.

JPG: Now, the trouble with identity signals is they can unify and they can divide. As we see in America, identity signals that used to mean Americans now means just your Americans, and then they split. This has been a constant hassle with human beings.

JPG: Now to the voices. The capacity to time travel and think about your own thoughts is bound to also make you wonder, this part of me that's thinking about myself, how can I think about myself? There's two cells and the brain is splitting. You know Julian Jaynes in the old days, an hypothesis that's probably not physically true, but it's true in an important metaphorical way. As humans began to be able talk to themselves, which is essential for planning ahead of time, then they thought the voices were coming from outside from God and stuff, and that they were being told what to do. Then it changed this theory, they caught on, "Whoa! It's inside of me." That capacity to talk to yourself, which we now know the biology of is called the default system in your brain, and it is the capacity that operates when you stop focusing on something and you just sit there or even when you're sleeping, the brain never turns off. It just activates the default mode, which is introspection.

JPG: You talking to yourself, not necessarily. Also, your ability to plan, your ability to imagine is introspection. But this division between a self that sees and evaluate and the self that acts gives rise to the feeling that one of those is corporeal, the self that is being told what to do or being assessed or being... and one of them is kind of not corporeal. It is somehow spiritual because it's... you can notice by the way, humans can... I'm doing it right now. You are too. You can look at yourself almost like you're in a third person game, and be thinking in the default mode, "What am I saying? What are these people thinking?"

JPG: That gave humans two things. The idea that that self might be able to go elsewhere, either live forever or... Then 40,000 years ago, you get shaman, going into caves and there's pictures, which are certainly part of a ritual. In the picture is animals that they hunt, but also creatures that are half human and half animal, which is the shaman. The shaman is there because the community is concerned, the animals are running out. They're hunting them and they're leaving. The shaman is going to go into this religious ceremony for their community, and he's going to take this part of him that isn't necessarily corporeal, and he's going to, for the community because he's going to not only get to talk to him now, it's going to talk to the spirits and he's going to go to their land where they're incorporeal part is, their spirits.

JPG: He's going to beg them to stay, to allow themselves to be hunted and form a relationship. Now, that idea of time traveling in space and time for a community to get forces that aren't in our bodies that are spirits or gods or devils or angels that the shaman does, is done all over the world to this day. It's not the least bit uncommon. It's still there. The evidence, the shaman is a healer because he's doing this to heal some remedy and a person in the community. Here's the fascinating evidence. When a shaman does this, goes on, has a vision, comes back, and the vision heals you, may have camps, you may have something else. It works only under one condition. And that is, first of all, the whole ritual has to be done communally in a group that knows each other, and everybody in the room must believe it and everybody has to participate. When they do, it works. Now, that's another finding we know. Nothing surprising at all, because to humans, there is absolutely no difference between mental distress and physical distress; both of them produce a stress hormones that are inflammatory and damage you.

JPG: You can only really heal yourself by getting rid of them. Community that is stressed by inequality or drought is just as if you are out there beating them up. The cure is the same. It is either you use the body or the mind to stop the stress hormones. Now, let me just conclude to say that you and I live in the country with the most anxiety, depression in the world. We can measure that by the amount of stress hormones in your body, and we are off the chart. You talk about the hockey stick, I mean, we are off the chart. Inequality gives rise to this. The evidence for that is now beyond belief that high inequality gives rise to stresses because each person feels it doesn't really matter because it's all rigged. Then they get physically sick and they have massive health bills.

JPG: What happens; people look for a sense of belonging and mattering that will make them feel safe, and that they create identity signals around that. If they can't find one that is healthy, for others, they find one thats toxic, because humans have a dire need to belong, they're herd animals, and therefore they will find their belonging where they find it. And a society that lets them find it any old way they do looks just like ours.

HJ: Now, even reading the book, seeing it brought together in that way is really, really powerful.

JPG: Well, thank you.

HJ: I think you you've already started down the path I was going to take us next, which is this book is full of metaphors, analogies, comparisons, one whole string of which has to do with the animals and humans. And you begin the book talking about termites. As you go along, you'll get deeper and deeper into mammals and particularly barnyard animals for reasons that will become clear, but also you're talking more about monkeys, you're talking about fish and birds, even sea monkeys at one point, although metaphorically, a metaphor built on a metaphor. No reptiles that I noticed, but-

JPG: It's an oversight. You could use anything. Look, I just found out recently the best example of a social animal that does... identity is so strong, it constantly is driving their culture are naked mole-rats. Again, I told you, animals are out there. You're not watching, Henry. I'm not watching. They're out there doing all sorts of stuff. Now there are people who actually... I think it's a great story. For years people taught... I actually wrote an article about this years and years ago, that only in songbirds, only males sing. That's quasi true in the United States, but birds didn't originate here. Around the world, we now know it's not the least bit uncommon for females to sing. Then of course you get the inevitable story from a graduate student who's now become famous saying, "Well, back when I was working with Joe, I certainly heard the females singing, but I wasn't about to tell Joe because he said I was crazy."

JPG: The thing is, when you look, it's always different. It's not right. Now, back to the metaphor. First thing to say is, here's another human property, but this is the property of all animals. Evolution would never make you care much about truth. It couldn't. There's no mechanism in which it could for two reasons. One is, you only see the parts of the world that you have the senses for. Other animals have different senses and see vastly different things than you do. Many of them much, much better, but not all. Therefore, you're not seeing the world. You're just seeing your world, the human one. What the Germans call your [German].

JPG: But second of all, anything that you believe or... we learn from our experience, and any lesson you learn from experience, if it works to keep you alive and pass on your genes but is false, it will get passed on. But if it's true and doesn't work, it won't get passed on. Evolution cannot be tropic to truth for those two reasons. Furthermore, humans use beliefs, that is, these conscious beliefs that come out of our thinking to ourselves and mulling and talking to others. We use beliefs as identity signals of who we belong to. We do not use them in primarily the truth. That is why every human is deeply prone to what we call confirmation bias, but a word that uses much better is my side bias. The beliefs are the identity signals of your side, and your side is what's keeping you alive. Remember this, sense of needing to matter and belong.

JPG: Therefore, you're not about to care whether they are true or not, because your beliefs are a cheerleading for your team and your team is all you've got. By the way, confirmation bias is as bad or worse in educated people as it is in uneducated people.

JPG: All right. Metaphors. First of all, the only way you can do novel work, and this includes science, if you were trying to understand and do domain, by definition, you don't know how to describe it correctly. You don't know all the true things about it. The all the way in is a metaphor. You first try to make a metaphor and learn something, and then it may be, maybe you cash out the metaphor later into actual descriptors. Now, some of the animals stuff, like the termite mounds, are not so much metaphors as fodder for humans to think because those animals all had different niches they had to survive in, and over billion of years, they solved problems that humans have been utterly unable to solve.

JPG: Over the last three years, I've taught a class in architecture at ASU with some architects, and the mound is a masterpiece of architecture, of self-designed, self changing, self-transforming architecture that is in and of the earth. It's masterpiece we've noticed. We have plenty to learn from it. Now, think about this; the American army is stuff is tried for untold amount of times to get an airplane that could hover the way a hummingbird does and make it out of not metal because if you try to do that, hovering with metal, it just breaks very quickly. Well, hummingbirds have been doing it for millions of years. We still can't do it. Not surprisingly, people want to look at what they did.

JPG: It turns out though, you can get inspiration, but you still got to... you've got to get as smart as evolution was. By the way, as you know, there are adaptive system ways now to discover stuff. Metaphor is a crucial, but the part that really interests me, and with your work in civics is important, I think, and that is, humans are not motivated by truth. Period. They're motivated by comfort, but comfort isn't trivial to them. It means you've got to assuage my fear of death, my fear of finitude, my fear that I don't belong, my fear that I'm unsafe. You've got to assuage that. Anything that will assuage that is very attractive to human beings.

JPG: Now, that doesn't mean truth isn't attractive. It means you got to make it attractive. The biggest problem we have is the bad guys are really, really good at making up comfort stories that aren't true, but we, and I know it's not easy, but we should be making up comfort stories that are true to show people that truth can be comforting. With the issue where we were talking about of unintended consequences, we humans now know, boy, stuff I believe that seems to work out in the short run sometimes really screws me in the long run. Well, then you can say, "Well, that's because in the short run, truth matters less than in the long run because sooner or later the world bites you." We have segregated the arts, the humanities and sciences in ways in which the function of storytelling or explanatory sense-making or motivating is in one side of the fence and the function truth is the other.

JPG: Then the side that can tell stories, we have put into school and made it canonical so everybody thinks nobody should have it because it's just classist elitism to. We have a society that has utter disdain for science, so we're in a mess. The only people I know... Henry, I'm sure you know many people who are doing this, but activist artists in participatory projects are doing this. They are activism around facts, but not ones that are not speaking to the needs of human beings. I mean, a good example would be, is we hear about white privilege all the time. The first thing to say is, it's so trivially true, I don't know why we'd have to mention it. There is no soul that doesn't know it's true. We've been talking about it forever, but we haven't done much about it. It's still there.

JPG: Talking and getting angry, but not doing anything just leaves the victims to be victims. Well, the reason is, if you wanted to do something, you'd have to get a team, that is, you'd have to do this planning function to get a coalition of people together, across some degree of diversity so that you could win. Telling them this simple truth when they have no job or three jobs and they're on opioids or they're... lost their house, that white privilege is hardly going to motivate them joining the coalition. Now, if your way of being in the world is saying, "I'm so moral that I will not collaborate with other people who don't agree with me in everything and won't own up to the facts that are important to me," good. Then what you ought to do is go to war and you see if humans in the beginning had had that attitude, the bullies would still be winning.

JPG: If we keep that attitude, the bullies are going to be back. I know as a former academic, even saying that white privilege is probably not the most motivating coalition-builder is probably the end of my career, but the career is already over.

HJ: Yes, it's nice to be at the point where got no fuck left to give.

JPG: There's really nothing bad you could do to me that I haven't already done to myself.

HJ: Well, a lot of where you're coming from comes from your new experiences as a gentleman farmer. I think one of the things the book maps is your progression from white trash to gentlemen farmer over the course of a lifetime. What are some of the lessons you're learning from your pigs, your goats, the other animals that you're talking about?

JPG: Tremendous amount of lessons. The irony is my brother's an identical twin, and so we both came out of white trash. At one point he lived in Cottonwood where I live and I lived in Sedona. Sedona is a fancy place, Cottonwood is rural. He couldn't take it. It was like going back to our relatives. He fled. Then I moved over here and it felt very comfortable. Thing about farming, one of the reasons I wanted to do it is it'd become very clear to me that one of the biggest mistakes humans made in their evolution history was standing up because most of the information is on the ground for us terrestrial creatures. If you get a pig or if you have a dog or you get any animal, the information they get off the ground chemically and electrically, and microorganisms off the ground is so far superior to what we have when we stood up and lost all the senses that would allow us, like smell, to be grounded.

JPG: Then we exasperated that by moving to cities, closing out microorganisms, polluting them. Returning to a farm... my farm is not a farm to farm the animals for food, it is to have the great pleasure to see domesticated animals, like ourselves, sheep, goats, pigs, donkeys, live out their entire life. Most of those domesticated animals don't get to do that. That's what it's about. But what they really teach you is, first of all, you don't know who an animal is. They're not humans and anthropomorphism is not necessary... They are absolute beings. They have their own forms of excellence and specialists. The one thing they are better at than humans by far is competence. You do not see incompetent pigs, you do not see incompetent birds. You don't. But I think I once saw a competent human, and that could have been I was drunk.

JPG: But the thing is, you learn a lot about the nature of that creature. First of all, you learn that everyone is an individual. That saying that there's a donkey nature, by no means, every donkey isn't different. It means there's limits to what you can do to the donkey, if you want it to flourish. In many ways, this is what inspired me, is I thought about, "Wow, if our school system had as bad a theory of donkeys as they have as humans and education, all the donkeys would be dead or stupidified." It's a metaphor in one way, but it's also to really go back to the ground being now in these architecture classes. Our theme this year is farming the future. That is, as the future gets cataclysmic and people have to participate and they won't be able to engage this industrial destruction of the earth, how do we get back to the earth in a participatory communal way?

JPG: There's movements like restorative agriculture, many others, that are really all about us, for a change, getting down back to the ground. We're going to have to do that or the earth will be dead. We're going to have to go back and take care of it. I think that anybody who lives with animals respectfully know that at one level they are like a different being, but at the very deepest level, there is a minimal difference between you and them. We share the same DNA. You look at the pig or the donkey, it has a tongue like yours, it sneezes just like you, it yawns. I look at these animals and I said, "Wow, the people who don't believe in evolution, why did God make every one of them yawn?"

JPG: I mean, it doesn't make sense. It yawns just like you and me. One of the great things is I have sheep and goats, and they separated evolutionarily a long time ago, but not as long as we did from chimpanzees. You can see that even though they'd been separated for several million years, in evolutionary time, that was yesterday. They look at each other and say, "Well, we're the same, guys." They can sense, and that's because they have identity signals of what goats or sheep are safe, and they can readily send them to each other and get into the same herd. And yet humans can't do it with other humans.

JPG: Anyway, the farm is a metaphor, but also a way to deal with the crisis of my retirement, which metaphorically, Henry, I retired January 2020, and then the whole world did. And I felt, "Wow. I didn't know I mattered that much to these people."

HJ: Well, there are places as I'm reading the book where you are speaking with such a lovingness of your pigs and critique of humans, and I'm fully convinced you like pigs better than you like humans.

JPG: I do. Look, every animal is special in its own way. But you cannot look at a pig, and pigs first of all, are weird because they care the most about food. They just deeply care about food, and they have no hard time finding food. Why are they so smart? I mean, they are incredibly smart. In fact, they outsmart me every day, and I say, "What are you guys doing? It seems like all you guys ever do is eat, and now we're out here and I look like a fool because you just figured that out." They never look unhappy. If they're unhappy, they go to sleep. If it's raining, they stand out in it. If they need some sun, they lay in it... See, they don't have any voice saying to them, "Boy, you should feel bad about how obese you are. You really should feel... It means your worthless." A pig doesn't care.

JPG: By the way, this voice inside of us that talk to us, it is the source of most of our power, but also a lot of our grief. The profession that is made out like a bandit because of this voice is therapy. But there is a very interesting case where a woman who was a scientist, actually studying the brain, got a stroke and lost that internal voice. One of the reasons is the internal voice is fueled by what's called the phonological loop, the ability to retain something for a couple of minutes, so it should keep cycling it. She lost that, so she could no longer hear a voice talking... she couldn't do introspection.

JPG: She had two effects. One was a lot of fear, and the other one was absolute joy that the voice had quit. It came back after years. But if you asked many people today, especially in a highly unequal society and a highly polarized society, "Would you just assume that we turn this voice off so you can be closer to a pig?" In an election that would win by a landslide because they're not living our lives. None of us got damaged by the virus. I'm sitting, we're sitting in nice, safe spaces with full salaries or pensions. The voice tortures me, but I didn't pay a very big price for that torture compared to what many people have paid.

JPG: Now, the way we have to help humans besides making truth motivating is we have to get people to turn the voice off as a voice of criticism and an anxiety and self hatred that is social, is sold to you by the society, and to turn the parts where it is planning and trying to think how to collaborate by getting into other people's perspectives on. Jaynes's bi-caramel mind is actually right. When the humans thought the other voice was coming from outside and then we found that; well, it's actually due to an internal mechanism in the brain. We thought, "Well, it's wrong," but you see the real truth of the matter is those voices are coming from outside you because where did you get the voices? You got them from your socialization, your family, your religions, your history, your media, and the voice that's talking to you, even though you say you feel it's Henry. Nope, it's Henry and a whole bunch of other people.

JPG: Some of those people need to be jettisoned from the voice. As long as you pretend it's your unique little voice, "I got to be me," and you keep those forces of culture and history that are no good, then you're just gonna make money for the therapists.