Cult Conversations: Interview with Caetlin Benson-Allott (Part I)

/In the following discussion, Caetlin Benson-Allott and I discuss her book Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing (2013) and get into the thorny issue of spectatorship, a theoretical model that has often been criticized for constructing “figures of the audience,” as Martin Barker put it, as opposed to the examination of legitimate audiences. We also discuss reception practices, as well as the growing shift from physical to digital media, considering the state of the landscape at this current historical moment. I thoroughly enjoyed speaking with and learning from Caetlin about her research (and more), and I hope readers enjoy our cult conversation too.

—William Proctor

Would you consider yourself a fan of cult media and/or horror cinema? Or is your interest in the subjects you study purely an academic pursuit?

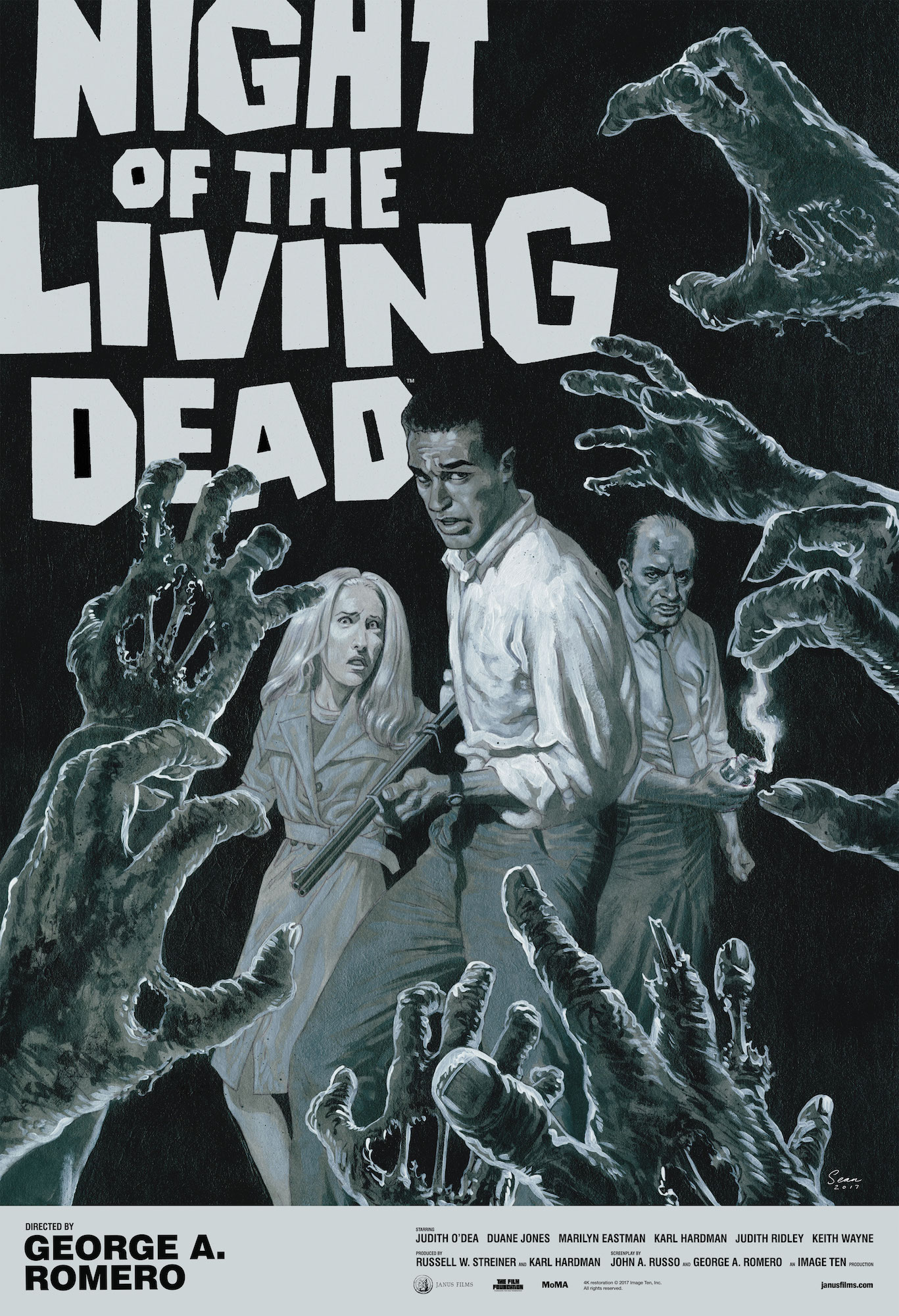

I am certainly a fan of horror film and have been since junior high. There’s a popular family legend about how I terrorized my younger sister with a Halloween screening of Night of the Living Dead (George A. Romero, 1968) when I was about thirteen and she was maybe eight. Night of the Living Dead later became a cornerstone text for my first book, Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens, and it remains my favorite movie to this day—so much so that I rarely teach it. So yes, I am a big fan.

When did your journey begin? What were the first cults objects you recall encountering in personal terms?

My journey began at a drugstore in my hometown of Lincoln, Massachusetts. This little stop had one rack of VHS cassettes for rent for a dollar each, which is about how much money I usually had on hand from my allowance. I must have been no more than nine or ten when I started renting from them. There was a proper video store one town over, but I couldn’t walk or bike there on my own, so that little drugstore was my first encounter with the autonomy of video rental and the pleasures of B movies. When I was in high school, Lincoln finally got its own video store, and I started working my way through its genre shelves, in part because genre rentals were cheaper there than new releases. As I recall, there was no rhyme or reason to what that store stocked; it seemed to follow the whims of its owners to an amazing degree. For these reasons, I consider videotapes my cult objects par excellence. They were my way into loving and living film history, horror most of all.

Apart from Night of the Living Dead, then, what did your adventures in video expose you to as a child? What are your memories of favourite films during the period?

I can’t remember when I first saw Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), but it must have been at an appallingly young age, given my deep idolization of Ellen Ripley and terror of the chestbuster sequence. Together with the Ceti eel sequence in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (Nicholas Meyer, 1982), the Alien chestbuster solidified my association of videotape with horror and bodily abjection. Today I would argue that the breaching of bodily boundaries that I found so thrilling and terrifying in those films helped me make sense of and enjoy the penetration of illicit (because violent) rental cassettes into the domestic sphere, not to mention the VCR itself. Of course I wasn’t thinking like that at the time, but I did love bringing the cassettes home to find out what’s inside the box, whether the movie would be as good as the packaging.

(I also loved Heathers [Michael Lehmann, 1988] and got in trouble for renting it for a friend’s birthday party. Evidently her mother considered that much murder, profanity, and abjection inappropriate for school girls!)

What I remember most about renting movies from in the ‘80s and ‘90s is just being absolutely indiscriminate in my choices. I knew nothing about film history or quality or genre. I loved Shirley Valentine (Lewis Gilbert, 1989), I loved The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963), I loved Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Roger Zemeckis, 1988). I think the other important thing to remember about our “adventures in video” back then was the promo art and the profound impact it could have one one’s sense of film culture. I vividly remember a window advertisement for The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989) from 1990, but it was well over a decade before I saw the film. My initial understanding of who Peter Greenaway was and where he fit in international art cinema came from the poster, in other words, not the film itself. I also learned enough about The Crying Game (Neil Jordan, 1992) from its poster and VHS box to argue (successfully) with my middle-school art teacher that it could never win as Oscar for Best Picture. (Unfortunately, I was right, and, as my teacher put it, the Academy will always be Unforgiven [Clint Eastwood, 1992]). Video stores impressed upon me the importance of paratexts and material culture for understanding film culture and the vagaries of taste and value within it.

If you were to summarise your book, Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing, for readers that may be unfamiliar with your work, how would you do so? Is this publication primarily for horror/ cult fans? Or do you think that other film scholars may find it useful in general terms?

Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens argues that video technologies have been the dominant platform of film spectatorship since the 1980s and that horror films provide a rich set of case studies for understanding how filmmakers understood and adapted to video culture.

This may seem strange, but I never considered Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens to be about horror while I was writing it (as a dissertation at Cornell University). Its working title was ImperioVideo, and I really thought it was about spectatorship theory and its failure to acknowledge home video. It was only at my defence that my committee pointed out to me that (1) what I was writing was a history as much as a theory of video spectatorship and (2) it was very much a history of horror filmmaking as related to video cultures. I knew that I knew horror better than any other genre, and I knew horror was crucial to the history of home video and its impact on film form and narration; I just didn’t realize I was writing a book on horror spectatorship until my beloved advisors pointed it out to me. (There was one chapter in the dissertation that wasn’t on horror but on video-era censorship and Y tu mamá tambien [Alfonso Cuarón, 2001]; it’s now a standalone article at Jump Cut.)

Today I would say that Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens has two really distinct audiences: horror scholars and spectatorship theorists. It’s so much fun to find out what’s meaningful in the book to different people. Some people are just there for the technology, others for the genre study. A few of us geek out on both. Obviously, I don’t think you can do one without the other. I also think there’s a lot to be said about horror in this era that couldn’t fit into Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens. Direct-to-Video (DTV) horror is a fascinating subgenre with its own conventions and social critiques. It deserves its own history, though, so I’m glad I didn’t try to condense it for a single chapter in Killer Tapes.

For Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens, you endorse spectatorship theory as a theoretical frame. How would you respond to criticisms of spectatorship theory as bound to imputation and the construction of what Martin Barker describes as “figures of the audience,” as opposed to empirical evidence, such as ethnography or audience research? Given the decades of audience studies that convincingly demonstrate that spectatorship theory treats audiences as a homogenous mass, what place does the tradition have in the twenty-first century academy? As Stephen Prince wrote more than twenty years ago, ‘the problem with film studies is that theories of spectatorship fly well beyond the data and in ways that pay little or no attention to the evidence we do have about how people watch and interpret film and television.’

First of all, I make a strong distinction between spectatorship and reception, spectators and viewers. You’re right that Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens is a spectatorship study; it’s interested in the ways that specific movies and their platforms create a subject position and interpellate viewers to occupy that position. Spectatorship studies typically have very little to say about how specific individuals or groups of individuals respond to such interpellation. That’s reception, and it’s best addressed through ethnography or historical audience research. With reference to Stuart Hall’s canonical essay, “Encoding, Decoding,” you might say that my research is more on the “encoding” side of the equation—which only part the story, but an essential part. Writing Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens, I wanted to know how motion pictures reflected the ascendance of various video platforms, how they encouraged their spectator to think about the issues those technologies brought up. How different groups responded to that encouragement would be the subject of another book.

With regards to the Prince argument you mention, I absolutely agree that some spectatorship theory has been ahistorical and universalizing in very problematic ways. This is especially true of 1970s apparatus theory that makes no distinction between various historical and regional iterations of “the cinema.” However, critics of apparatus theory tend to assume that because some of it was ahistorical, all approaches to studying any motion picture apparatus must be ahistorical. I don’t see why that has to be the case at all! We have a lot of data—not just on viewers but on theatre spaces, screen technologies and sound systems, and other material realities of film spectatorship—that should also be analysed. People do not watch and interpret film and television in a vacuum; the spaces within which they watch and interpret are never ideologically neutral. I am interested in the way that exhibition technologies impart and influence messages about how we should interact with them and what we should value (or abhor) about specific media content.

In the introduction to Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens, you argue: “after the cinema outlived its major video threat, it became economically ancillary to DVD distribution and now serves as an advertising medium as much as an exhibition platform.” While it is undoubtedly accurate that DVD has outpaced cinema in economic terms, what do you think about the impact of streaming services and the way in which this has impacted the sales of home video? Eighteen months ago in The Guardian, for example, an article claimed that ‘Film and TV streaming and downloads overtake DVD sales for the first time’.

Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens is definitely a history; its last chapter is on peer-to-peer file sharing—and almost no one uses p2p technologies for their movie piracy anymore. That’s ok, because what the book sets out to do is explore in an understudied moment in film distribution and exhibition between the cinema and streaming.

The improvement of streaming services and the continued spread of high-speed internet access have definitely impacted DVD sales, and all physical media sales are on the decline. But there are a lot of important questions we can ask about how different contemporaneous media platforms frame their content different. I recently finished a book chapter on the original 1978-1979 Battlestar Galactica television series (ABC), which has the distinction of being distributed on every major video platform since 1985. Right now, you can buy it on DVD or Blu-Ray, download it on iTunes, or stream it on any number of services. But each platform’s paratexts make a different argument about the series’ value and its place in television history—including none at all. Media platforms are not redundant; they all frame their content in a different way. Understanding those distinctions is crucial for understanding our current media ecology.

Following on from the last question, why do you think Hollywood producers remain fixated on box office receipts as a signifier of triumph or failure? For if home video remains economically dominant in relation to the box office—and I’m not saying that it isn’t—does it not make more sense for producers to turn their focus onto home video to determine whether a film is economically healthy or not? I am thinking in particular about the way in which films—Blade Runner 2049 (Denis Villeneuve, 2017) is an excellent example—are deemed to be failures despite clawing back over $100 million after production costs are factored in—and before home video sales are even accounted for.

The first thing that comes to mind is that video revenues trickle in slowly, whereas the box office figures we see in the news are usually opening-weekend reports. Opening-weekend reports are always timely, even if they’re not always that relevant to the long-term financial success or failure of a given film. They’re also free publicity. When I read about what a great weekend The Meg (Jon Turteltaub, 2018) had, I was reading about The Meg again, being re-exposed to the idea that it’s a fun, hip summer movie. If someone tells me now about how much money Blade Runner 2049 made in its first eighteen months on video, well, it doesn’t have the same effect. It does not feel like news.

Of course, all this begs the question of why newspapers are willing to report boring stories about weekend box office. I think we can assume there’s some corporate politics involved. But that question deserves to be answered by a media industries specialist.

Johnny Walker has argued that “about 70 percent of the 500 or so feature-length horror films produced by British companies in the twenty-first century bypassed theatrical distribution” and went ‘straight-to-DVD.’ What are your thoughts about the DTV phenomenon as it relates to horror released in the US? And do you think that DTV remains the ‘Other’ of feature film distribution insofar as the cinema remains marked by authenticity, while a DTV release is more ‘a regrettable triumph of convenience,’ as Barbara Klinger has noted?

I think people are increasingly aware that DTV and film distribution have permeable borders. Alex Garland’s Annihilation (2018) was initially distributed to theaters in the US but went directly to Netflix elsewhere. Back in the 1970s, Steven Spielberg’s Duel saw theatrical distribution in Europe while playing only on television (and 8mm) in the US. Duel was more on an exception, a telefilm that “rose” to theatrical exhibition, but such anomalies also received less attention at the time.

I think we are on the cusp of seeing a major change in what cinema-going means culturally, which will likely change how viewers negotiate the distinction between a DTV and a cinematic release. As ticket prices soar and theater owners offer more expensive, gourmet concessions, including beer, wine, and liquor, the ethos of cinema-going is changing, at least in the US. Almost all of the movie theaters in Washington, DC., where I live, offer plush recliners, assigned seating, and a bar in the lobby. They present going to the movies as a luxury experience, not a regular pastime. They often feature movies produced by Neflix, Amazon, and Hulu—movies that announce their future streaming platforms in their credit sequences. So if I go to the theater now to see a movie, it’s because I can’t see the film in question on video or can’t wait to see it on video. Rather I am going for the anomaly of the theatrical experience, which does not speak to the quality (or even the budget necessarily) of the film. How long that a theatrical release will continue to affect reception distinctions between films I would not want to guess—but I don’t think it will be long.

Caetlin Benson-Allott is Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor of English and Film and Media Studies at Georgetown University and the Editor of JCMS (formerly Cinema Journal). She is the author of Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing (2013) and Remote Control (2015). Her work on US film cultures, exhibition history and material culture, spectatorship theory, and gender and sexuality studies has appeared in Cinema Journal, The Atlantic, South Atlantic Quarterly, Journal of Visual Culture, Jump Cut, Film Quarterly, Film Criticism, Feminist Media Histories, In Media Res, FLOW, and multiple anthologies. She is a regular columnist and Contributing Editor at Film Quarterly.