The Blind Dead Series and the Spanish ‘Fantaterror’

/The ‘Blind Dead’ Series and the Spanish ‘Fantaterror’

By Martin Villare

I confess I am a fan of horror fiction, especially film. My dissertation as an undergraduate focused on “horror and taboo” as I was trying to tackle the representation of the unwatchable on many of the movies released in the 2000-2010 decade, a decade that saw the rise of so-called torture porn and the New French Extremity. After that, I moved on and I decided to focus on Spanish horror film since it had been largely ignored in academia and I believed it had turned to be one of the most interesting representations of the genre in the last years. The international success of The Others, Pan’s Labyrinth and Rec proved audiences that Spanish films could indeed be scary and good, but…why had not Spain produced horror films before? Or, if they had, how come many of those films remain still highly unknown abroad?

On this blog, Craig Ian Mann argues that there is a wider acceptance of horror at large and in part is due to the attention that academy and studios have given to the genre since the 1990s. Indeed, the fact that many journalists and scholars talk about a “Golden age of horror cinema” (see also on The Guardian, Vice, and Culture Vultures) is indicative of this rise of interest even though I agree with Steve Jones and Xavier Aldana Reyes that this trend is based on the fact that the press ignore low-budget horror film or the contribution of many “unknown” artists that have shot cheap, off-mainstream movies. In the specific case of Spanish horror film, the industry in the Iberian country did not start to make these movies until the 1960s. There were, of course, some dramas in the 1940s that even if they had few connections with horror, at least tried to deal with supernatural themes through oneiric narratives. El Clavo (1945), Embrujo (1947) and El huésped de las tinieblas (1948) are some of the examples. However, the great precursor of the Spanish horror boom of the 1960s was Edgar Neville’s La torre de los siete jorobados (1944), a tribute to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and at the same time an homage to Carlos Arniches, one of the best satirical writers of the 20th century in Spain.

However, Francoism never really helped to promote the national Spanish horror genre. When the Spanish horror boom started in 1968 after the release of La marca del hombre lobo/Frankenstein’s Bloody Terror (1968), only La residencia (1968), directed by the successful Narciso Ibáñez Serrador (creator of the famous and iconic Historias para no dormir for the national TV channel), had been given subsidies. Thus, most of the films made in the next years were low-budget, shot in a few weeks and often co-produced. Luckily for the national horror film industry, worldwide cinema saw a popular resurgence of the horror genre; and after the success of Night of the Living Dead and the end of the Hays Code in the USA, more and more challenging films started to be made.

So what do we mean when we talk about the Spanish Horror Boom? To start with, in Spain and in Spanish film studies the trend is called Fantaterror. Paul Naschy, creator of Frankenstein Bloody Terror and its sequels about a crazy wolfman, coined this term because he was annoyed by the pejorative definitions and adjectives the Spanish press used for movies within the genre. The term involves two separate genres that did not have any particular history in Spain: fantasy and terror. And while it is true that we should not confuse both of them (since not every fantasy film is horrific and not every horror film is fantastic), it is evident that the same people who made Fataterror movies from 1968-1975 mixed ingredients from each genre equally.

The resurgence of international horror cinema opened a Pandora’s Box for Spanish horror production. It has been said that the British Hammer had a great influence on some of the most popular Fantaterror films. In fact, these years saw the appearance in Spanish movies of some of the most famous classical monsters: Dracula, Frankenstein’s creature, the werewolf, the mummy, and of course Amando de Ossorio’s Templar Knights.

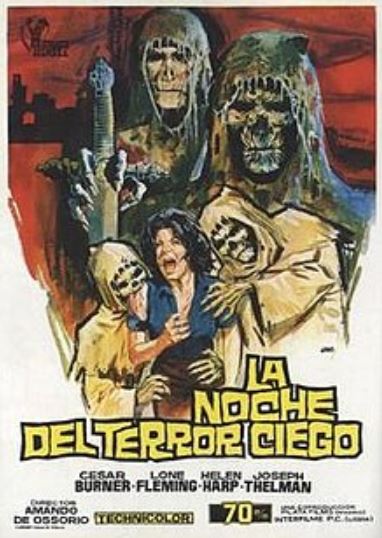

The Templar Knights (also known as ‘the Blind Dead’ series) were an original contribution from Ossorio to the international “monster film boom” that was taking place in many countries. The first instalment was released in 1971 and for four more years three sequels would be eventually released. The success of La noche del terror ciego was indisputable and proved that the national horror cinema was very much alive. The story of young friends who have to face the resurrection of putrefied boneless Templar Knights conquered the Spanish audience and allowed Ossorio to continue making the rest of the films.

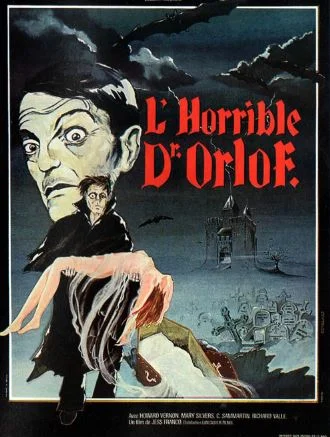

The tetralogy is now considered a cult series. Along with Waldemar Daninsky, the wolfman of Paul Naschy, a character that definitely fits into the same tradition of Craig Ian Mann’s studies on the werewolf, and Dr. Orloff, protagonist of Gritos en la noche/The Awful Dr. Orloff (1962) shot by Jess Franco in France, is the most famous example of fantaterror. However, unlike its counterparts, the monsters of this series are completely original and do not have any previous filmic reference. This is one of the reasons why I chose these films to talk about the Spanish cinematic tradition of the time during late Francoism and the changes that society was experimenting with. The other reason is that these films explicitly made reference to the political climate of the time. It has been argued that ‘the Blind Dead’ series represents allegorically the threat of Francoism against the progressive movements that were taking place inside the country. The return of the dead back to life, eager to destroy the new changes of society and its “modernization”, can therefore be interpreted as the fight for the traditional values of Francoism.

After the success of the first instalment, La noche del terror ciego, which had attracted 789,579 viewers and box office takings of 163,324 euros of that time, the Templars were revived in three consecutive films between 1972 and 1975 (El ataque de los muertos sin ojos, El buque maldito and La noche de las gaviotas). Ossorio’s formula, which combined Gothic elements, adult themes and saleable scenes of sex and violence, responded to the international success of Romero’s Night of the Living Dead.

Kim Newman describes Ossorio’s Templar as “uniformly tiresome – it seems as if everybody in Spanish horror film is compelled to wear Carnaby street dresses, polo-neck pullovers or macho man medallions”. Although these creations clearly form part of the zombie subgenre, the director is at pains to distinguish his monsters from zombies in a clear attempt to move away from Night of the Living Dead.

According to Ossorio, speaking in the July 1978 edition of Fandom’s Film Gallery,

1) The Templars are mummies on horseback, not zombies. A displacement in the relationship in Time/Space slacks their motions. 2) The Templars come out of their tombs every night to search for victims and blood, which makes them closely related to the vampire of myth. 3) The Templars have studied occult sciences and continue to sacrifice human victims to the cruel and blood-lusting being that keeps them alive. 4) The Templars are blind and guided by sound alone. All of this makes them entirely different from zombies or any other kind of living dead creature without soul or reason.

It is interesting to note that in an attempt to differentiate his creatures from zombies, Ossorio gave his Blind Dead films a uniquely Euro-gothic aesthetic by replacing explicit cannibalism with vampirism (a central theme in European folklore) and introducing pseudo-historical details, lashing of soft-core sex, sadism and occultism. By considering these creatures a mixture of vampire and mummy, Ossorio sees attributes of both in the knights. Like the vampire, they return from the dead at night seeking blood (and in the first movie, La noche del terror ciego, they even bite and convert their victims). Like the mummy, they come from a distant past and irrupt into the modern world of the narrative in order to fight it. The films represent a confrontation between tradition and a series of modern elements; namely, the new patterns of sexual behavior emerging from the Spanish economic boom of the 60s and the changing social context. The appearance of the Templars symbolizes ‘the rising of an Old Spain against a new permissive generation,’ something that the films symbolically use in their mise en-scène, iconography and editing. Therefore, we can see a parallelism between the Blind Dead tetralogy and the propagandistic movies (cine de cruzada) of the 40s, the first decade after Franco took office.

Tombs of the Blind Dead (1972)

The mere presence of the monstrous Templar Knights and their monk-warrior uniform is in a way a critique of Francoist institutions and values. Since 1939, when Franco won the war, the regime’s propaganda fought to justify the conflict by saying that it was a crusade for defending the Catholic Church and traditional Spanish values against the Red Horror and the international Marxist conspiracy. Franco himself accused the Freemasonry of being behind the Republican side. Obviously we can relate the secret society of Freemasonry with the Templars, a secret Christian organization that was expelled from the Church, and whose legend is used by Ossorio to portray a satanic cult that seeks eternal life. Although the appearance of these zombie crusaders is anachronistic, they summon up a very recent past, threatening to return at a time when the Francoist state was disintegrating.

It is important, then, to understand what values cine de cruzada and the Blind tetralogy tried to overcome. When Franco started to run Spain in 1939, prohibitions were enforced by a brutal and unforgiving regime that attempted to unify society, allowing very little personal freedom to the individual and brutally punishing transgressions. The traditional mechanism of social control in Spain, personal honor, or “a good name”, is seen in post-war films (Raza, Sin novedad en el Alcázar, Los úiltimos de Filipinas…) to be more important than personal enjoyment or satisfaction. These films use history as the basis for a non-historical elaboration of the themes of brotherhood, tradition, crusade, obedience, self-sacrifice and a sort of transcendent experience of masculinity.

Ossorio’s films use the cine de cruzada movies as reference to portray a battle between the traditional values symbolized in the Francoist regime of the 1940s (that still continued to exist in the early 1970s), and the struggle of the new generation of young Spaniards to move forward and recuperate more liberties.

Martín Villares is a PhD student at University of Southern California where he especializes in Spanish Film under Francoism. Previously he had pursued two bachelor’s degrees at University of Carlos III de Madrid (Journalism and Film &Media), a master’s degree at King’s College (Film Studies) and another master’s degree at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spanish Language and Literature). As a researcher, Villares’ main interests are the horror genre and also Spanish films (essentially since the end of the dictatorship until the present). In 2015 he published his bachelor’s thesis (Pornography of death) in a film journal in Spain (Scifiworld) and later on he analyzed the horror film within Spanish cinema in early 70s as part of his dissertation in the English university. At this moment he focuses on Spanish horror in the early 1970s.