Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Kishonna Gray & Lori Kido Lopez (Part II)

/Kishonna

I am so glad you mentioned that wonderful text. I was deeply engaged with the narratives that By Any Media Necessary. I am recalling the powerful stories of the undocumented youth and how they employed digital technologies for this empowerment. Mobile media, YouTube, social media and other forms of social and tech media have been significant in illustrating new ways to politically participate especially in getting those often overlooked and marginalized stories into the larger body politic. But then I immediately thinking about the vulnerability of these youth and marginalized folk. Especially for undocumented folks, the DREAMers, Muslims, Black folk under constant police surveillance, and there is larger engagement with law enforcement agencies to track movement and actions of activists.

I think my scholarship being focused on gaming, benefits so much from this text. It gave us detailed documentation of the ephemeral activities of youth within digital culture. I often think about the hidden and often invisible experiences of gamers that are only becoming more visible now with the increasing streaming culture. But women of color continue to the be the most invisible population. But the level of participatory culture of private spaces within gaming illustrate the multiple modes of engaging within digital culture. I am thinking about these spaces more as intersectional counterpublics—where these women engage digitally and also physically with their communities IRL. I link this to Sangita Shresthova’s chapter on Storytelling and Surveillance where the term “precarious publics” is invoked, which illustrates the level of empowerment by youth but also more at risk in making their voices public. So that’s one of the most fascinating thing about this book and associated tech, is its acknowledgment of not only the ever changing landscape of participatory politics, but also how marginalized populations are sometimes never able to utilize it similar to their counterparts.

Lori

Yes that’s a great point, Kishonna. That one of the difficult things about judging the impact of our contemporary moment on digital participatory cultures and political engagement is that so much is shielded from view. Your work on Black women gamers brings to light a subculture that would otherwise be largely invisible, and is certainly not often examined within media studies research. My current research deals with a similar phenomenon in the case of Hmong Americans and their development of what I call “micro media industries.” Since there are so few Hmong in the US and they have no home country that might have developed its own media infrastructures, Hmong across the diaspora have been incredibly innovative in relying upon the affordances of digital and mobile media to produce their own communication networks.

For instance, Hmong communities have developed a form of radio that relies on conference call software and is accessed through cell phone calls, which makes it easier for elderly refugee populations with less mobility and literacy to participate. Hmong women have used this participatory platform to engage in community-wide conversations about serious concerns like international abusive marriage and other misogynistic practices. Such conversations clearly fall within the category of counterpublic that Kishonna described earlier, as they are impenetrable to outsiders and allow participants to debate these issues as a community. This can be helpful since many women who suffer from this practice are in extremely vulnerable positions, and the larger Hmong community often prefers to deal with this issue without interference or judgment from outsiders. Yet it may also limit the potential for Hmong American activists to draw helpful attention when it is needed, or to use the strength of these participatory cultures to engage in political issues such as fighting against anti-Hmong racism and violence from white Americans. So I guess another area I appreciate scholars looking into is how digital counterpublics can more effectively pivot from the protection of the enclaved counterpublic to being able to mobilize for more public and visible engagements, and how they can maintain their integrity and sovereignty even as they do so.

Kishonna

Lori, I am fascinated by the micro media industries that your work illuminates among the Hmong community. I often think about invisibility in disempowering terms—how not seeing leads to further marginalization and isolation within mediated frameworks. I’ve also examined questions of invisibility in relation to the systematic oppression that pervades the digital lives of women of color (similar to what occurs in physical spaces). For example, I investigate questions of invisible marginality through women of color’s continued absence as playable characters in video games, to their hyper-visibility as sexualized non-playable characters, and track gamers’ perception of these depictions.

Using hypervisibility in body politics, women of color are represented in stereotyped and commodified ways throughout gaming and marginalized in online gaming spaces. But with this example that you highlight, I am think about the power of this invisibility, in that this example illustrates the power of this enclave. I want to begin exploring the possibility of there being a level of protection and solidarity within invisibility from larger hegemonic audiences and structures.

I think your work gives us a way to engage the dialectic: the process-oriented rather than result-oriented. For instance, in studying social media influencers in Ferguson during the aftermath of the death of Mike Brown, individuals often explored the utility of Twitter but more in terms of what the technology can offer to fulfill larger goals of police reform.

The focus was on how Twitter could be mobilized to lead to actions—a result-oriented focus. With the example from the Hmong community, it may be possible to see the nature of the process—from creation, to see how digital spaces and their associated communities and networked enclaves can provide protection. I see a level of protection with this level of containment if you will: protection of their intellectual contributions, protection from harassment, protection to create and sustain digital sovereignty, etc. From your work, and linking this back to women of color in gaming, I want to root some of their engagements as self-consciously eclectic, critical and deconstructive. Not really seeking paradigmatic status and most definitely not trying to obey established technocultural boundaries. In this way, they are the producers, consumers, creators, disruptors, resistors, etc.

Lori

Yes, I like the idea of considering the process in addition to (or perhaps instead of) focusing on results. I really appreciate the work of Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa in helping us to understand hashtags as field sites for doing ethnographic research, because in doing so, we can unearth the rich and complex ways that hashtags gain meaning. Instead of just asking what #BlackLivesMatter has accomplished, it’s important to think about the ways that tweets can do so many different things—including allow diverse voices to participate in an aggregated conversation, call attention to what is being left out of mainstream discourse, learn about events as they are unfolding, mobilize on-the-ground actions but also allow for support from a distance, and so much more.

Of course it’s also the case that the framework of “participatory politics” has much to offer us in the case of considering Black Lives Matter, and I think that’s a nice place to end our conversation that has largely considered how race and racism have shaped our research on media and participatory cultures. If we are thinking about how young people are using digital technologies to engage in the political issues that matter to them, Black youth who have used Twitter to address anti-Blackness and state violence should certainly be a key example of how these possibilities continue to grow and evolve alongside our changing technocultural landscape.

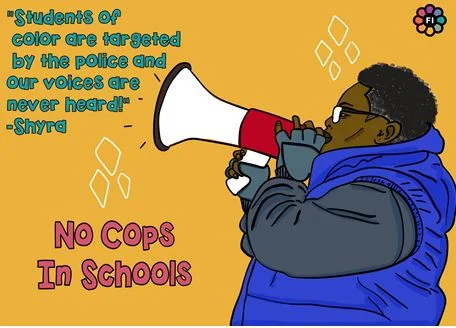

In my own community, youth of color from an organization called Freedom, Inc. have been deeply engaged in the national Movement for Black Lives and are now using what they have learned to impact their own community. Recently they have been mobilizing to remove police officers from Madison’s high schools and increase support for students of color. It’s been incredible to see how the global development of a civic imagination around Black liberation and decolonization has been taken up in local communities, facilitated through digital technologies. There’s plenty more to be said about this topic, but I think it’s about time to wrap up and I do like the idea of ending on a positive and expansive note—considering the ways that even in this bleak political moment we are still able to see many possibilities for transformative politics and increased civic engagement.

___________________

Kishonna L. Gray (@KishonnaGray) is an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois - Chicago with a joint appointment in Communication and Gender and Women’s Studies. She is also a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. She is the author of Race, Gender, & Deviance in Xbox Live (Routledge 2014), lead editor of Feminism in Play (Palgrave-Macmillan 2018), and co-editor of Woke Gaming (University of Washington Press, 2018). She is currently completing a manuscript entitled Intersectional Tech: The transmediated praxis of Black users in digital gaming (LSU Press).

Lori Kido Lopez is an Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Studies in the Communication Arts Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she is also affiliate faculty in the Asian American Studies Program and the Department of Gender and Women's Studies. She is the author of Asian American Media Activism: Fighting for Cultural Citizenship (2016) and co-editor of The Routledge Companion to Asian American Media (2017). She is currently a co-editor for the International Journal of Cultural Studies.