Throughout, you draw examples across a range of different media forms, including oral stories, literary texts, films, television shows, and drama, among others. To what degree is the art of storytelling (and its classic functions) indifferent to medium? At what point does the affordances of media enter into your analysis?

The more I think about it, the less I believe that “the media is the message.” Frankly, I think the message is the message, and content is king. There is a set of vitally important ideas that facilitate our advancement and survival. It is the responsibility of the artists working in various formats to find unique ways to convey the wisdom of life continuation.

In fact, it is the uncritical acceptance and superficial understanding of this well-know maxim that leads to embracing the inevitability of our gadgets becoming more important than our stories. This implies that we should not “bother” with content. We must resist the idea that the story is “out there, anyway, inside the machine.”

I was a graduate student in the 1990s, and of course this was the motto of the day. McLuhan’s paradoxical revelation was profound and timely. It also resonated with a similar one, “form is content,” proclaimed prior to McLuhan, as a new theoretical paradox and paradigm by the Formalists in the 1920s. This idea meant to explain to the confused contemporaries of emerging modernism that all these crazy paintings and poems had profound meaning and that their form functioned as content, and already had embedded and encoded ideas within visual and narrative representation.

The logic behind the idea that “form=content” aligns with the belief that “medium=message,” and is very familiar from the study of art theory. The most valuable insights of the Formalists’ and McLuhan’s maxims are the degree to which form/medium affects and defines content/message. The Formalists’ ideas were later developed by the Structuralists, who looked into the overall complex dynamics between form and content, which generate multilayered messages that affect us on conscious and subconscious levels.

When McLuhan’s maxim is not invoked as an excuse to abandon content, we may find some truth in this approach. In fact, in Fictional Worlds I followed the Formalists, the Structuralists (who effectively complicated this formula) and Turner, in detailing how each genre, and many story formulas, already have – or have encoded – a powerful content found innately within their construct.

The writer can unlock this symbolic content to achieve great impact on the audience. This embedded architectonics, when learned, can free a writer because the iron carcass of the “story form” allows the creator to experiment. Providing a structural “safety net,” the story form enables the author to go in any direction, employ fantastic beings, travel to distant islands/planets, as well as unleash on the fictional world dangerous crises and enlist diverse heroes with problem-solving skills. The logic of the form will make the Journey balanced and powerful. Yet, a certain amount of freedom remains in the hero’s journey formula, allowing even radical experimentation with “story logic.”

The influential and wise screenwriting guru Robert McKee, whom I highly respect, noted that he teaches form but not formula. I think it is his response to the “get-rich-quick” superficial use of the Hero’s Journey.” This trend, triggered by the success of Lucas’ Star Wars, has been evident among some aspiring screenwriters in Hollywood.

In fact, I argue that a thoughtful approach toward both the logic of “the ritual story” and the logic of “the dramatic arc” are very important for writers, and are interlinked. I explain these profound connections and propose creative writing methods based on formula and form in chapters 3-6 of Fictional Worlds.

The crux of teaching the dramatic arc is Fictional Worlds’ “golden rule of the three Cs” – encouraging writers to take maximum advantage of every decision-making situation and moment of choice (correct or flawed), at each dramatic crossroad. This, incidentally, is what unites drama and games. Extensive discussions of these issues in my classes led to the conclusion that dramatic form must boost the trajectories of choice in any story, while games will develop in the direction of multiple choices and roads (more forking paths). Instead of a “right” or a “wrong” move by a gamer, transmedia can offer a spectrum of crossroads and trajectories which may lead to many “right,” but diverse, approaches to the successful Journey. This is what the new generation wants, and this is what makes sense to me.

A fandom is often described as a community which self-organizes around their shared engagement with a story (or storyworld). What similarities or differences would you draw between contemporary fan communities and the older forms of“symbolic communities” you write about in the book.

There are many ways of looking at this phenomenon. I would highlight three angles: fandom as a spontaneous ritual-symbolic activity, as discursive communities, and as a social movement. These modes overlap.

If there is any “master theory” of fandom to be found (to refer to your dialogue with Mark Duffett), I suggest it will be in anthropology, in ritual theory. Symbolic anthropology also explains why “performed identity” is inseparable from “transformed identity” within the ritual framework, as I also argue in Fictional Worlds.

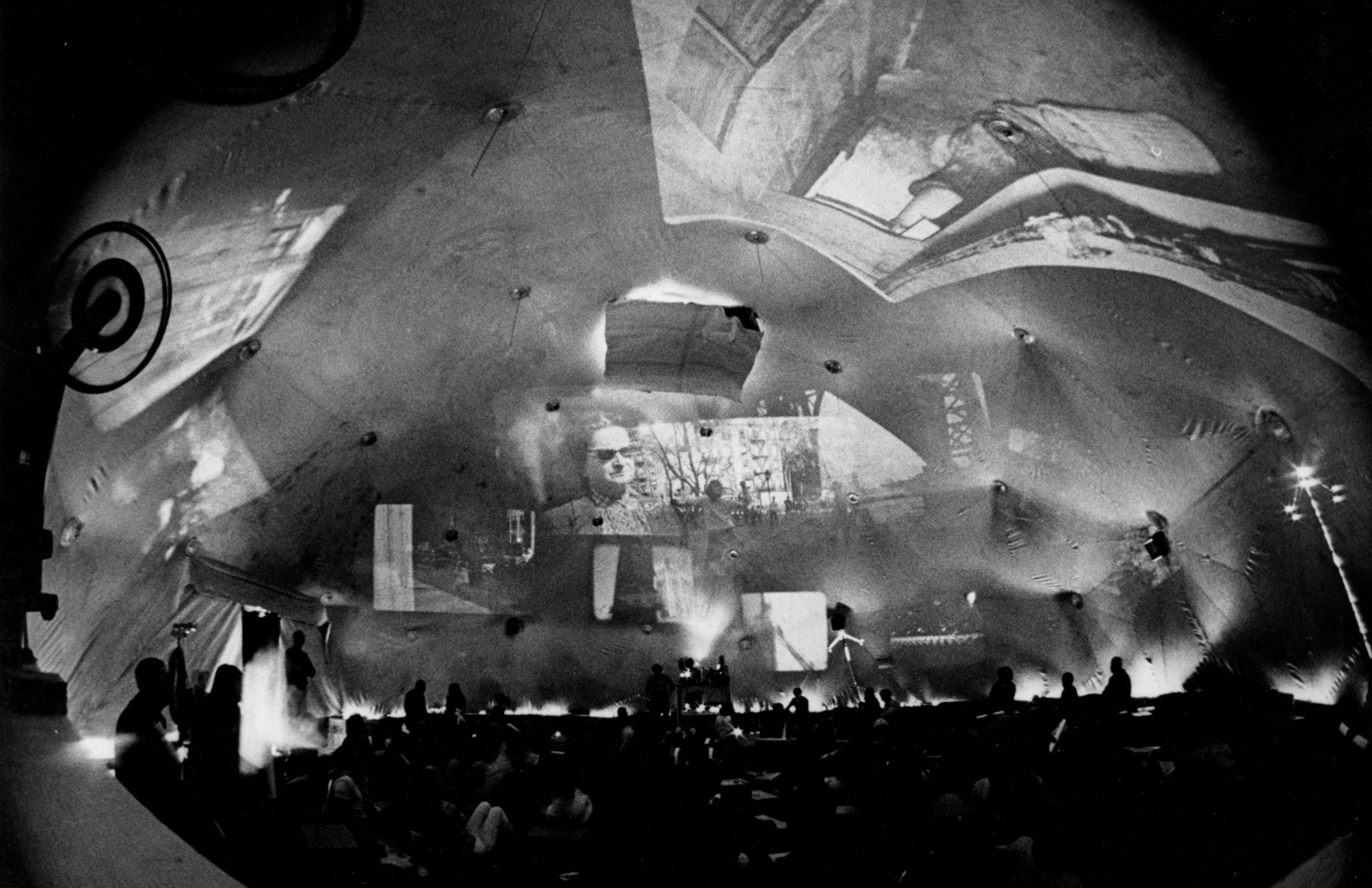

As a ritual-symbolic activity, fandom signals that many people seek transformation, adjustment and belonging to a new group. Since ritual activity per se is not practiced by modern societies and the media is only partially effective in meeting these cultural needs, the numerous un-initiated and un-adjusted take matters into their own hands and create networks in which they try to achieve initiation, transformation and social adjustment.

In fan communities, the divine Donor of New Knowledge is the Author who creates the environment of the transformative Journey in which adjustment is possible. The Initiating members of traditional rituals took the Initiands into imaginary mythic-symbolic lands. Many modern stories transcend textual boundaries and expand into fandom activities that come closer to such promise. Consciously or subconsciously, spontaneous fandom communities are, in essence, “initiating themselves.”

There will be mixed results because each fan group’s choice of Great Book or Cult Movie boxes them in, limiting “new knowledge” to that contained in the text. Similarly, “new values,” essential for the sacred Journey, may be defined by the “Initiators,” the leaders of this fandom group. Sort of “masters of ceremonies,” keen on seeing opportunities for power, they may advance themselves within the local fandom hierarchy. Despite such possible power games, fandom indicates that the need for ritual structures and rites of passage of all kinds is great, and the void is not filled.

Discursive community is one which is typically organized around a text. The fandom unit is a form of discursive community, focusing on a particular Book/Movie. While on the path to initiation, such fandom groups employ their chosen “sacred” text in place of the sacred myths which used to be communicated to Initiands within traditional ritual. Unlike the traditional Hero’s Journey with its thresholds at which the hero confronts ordeals and tests, fandom units select and reenact scenes from their Book/Movie for such threshold experiences.

As a social movement, fandom signals that there are a considerable number of people who are determined to seek new knowledge within a variety of “possible worlds” and to explore them as templates for social development. This also signals that they have more trust and interest in fictional worlds than in their familiar reality (the current state of society, law, ethics, politics, etc.), as exploratory fields for the future. Avoiding arguing with, or openly criticizing, society, “fandom crowds” turn to new, albeit fictional, side roads to examine possible futures.

On the dark side, there are pitfalls. I recall a student in my Writing for the Media class, a graduate course in which students were expected to produce an episode for television in any genre, with an option to write it as a pilot that they could submit to the networks. Most students elected to do a pilot, which meant that the quality must be better and the story more persuasive in order to entice a network to consider such a new series. After two months of studying the nuts and bolts of storytelling, the students submitted their screenplays.

One student chose a fan convention in a hotel as the setting of the assignment. Her screenplay project featured a fashionable bunch of Medieval-Gothic-Aliens, or something like this, drawn from a variety of comics, movies, and TV shows. Her play was about the protagonist (her alter ego) changing costumes – I can imagine! – and visiting different hotel rooms where others would comment on her costume and “like it,” and “accept her.” Then she would then go back to her room to change her clothing, and “repeat, repeat.”

There was no action and no story, just suitcases with costumes. I offered this student all kinds of storylines that might happen in such a (weird) “crossroad” place (in the tradition of the movie Grand Hotel). I explained that the play did not exist without a story, and she decided to choose one of my suggestions: that eager, costume-changing young parents do not notice that their toddler walks out of the hotel room and vanishes. This plot provided an instant chill, imagining how she wanders alone surrounded by the Medieval-Gothic-Aliens, each one scarier than the next. Then the crowds rush to find the girl; they are dressed accordingly and are unaware “who is who” (friend or foe; we have mixed elements of mystery, tragedy and farce). But, “our” glorious protagonist turns out to be courageous and smart enough – she’s the one who finds the little girl and saves her from the clutches of… (enter your villain type here). The student liked the idea and promised to make it work (a cliché really, but at least drama: a quest to find a missing child, peppered with some macabre visual irony and options for interesting quirky scenes).

Imagine how stunned I was when at the end of the semester the student removed all the elements of the story and turned everything back to “she changes costumes and people like her;” because “this was good enough,” she said. For her, just as in ancient rituals, this “mystic” changing of skins was a magical entrance into a mythic world. The rest was irrelevant.

Of course, some attitudes within fandom are not about the self or others, transformation, or even belonging. The focus is on a pageant or “ceremony,” a popular culture phenomenon already mocked many times, as in Little Miss Sunshine, Miss Congeniality, etc., where showing costumes – fashion – is the goal. Even the delicious monsters of this student’s story setting – such a rich resource for any magic tale! – were not employed to shape the story. They served as decorations. This is an example of fandom as a rather superficial activity. Yet, I do think that the author-protagonist really wanted the Heroine’s Journey, but she did not yet know it.

I was pleased, however, to recently discover a website which highlights fandom as a transformative activity: http://transformativeworks.tumblr.com/

Across cultures and eras discursive communities have always been present. They were organized at first around a sacred story, and later around a book, film, or artist. Some discursive communities moved beyond their chosen text, developing higher goals, new communal ethics and worldviews. They also fueled social movements, becoming effective symbolic communities and advancing their societies.

In the book, you argue that horror does not actually constitute a genre in the sense you are using the term here. Explain.

There is no question that horror abounds in screen culture and the media. But is horror a genre? If one accepts the functionalist approach of Fictional Worlds toward genre, and its anthropological genre theory, the answer is no. There is no cultural need behind, nor community-building or life-asserting function featured in, horror.

I argue that horror is a narrative “fragment” of something else (perhaps the “ritual story,” the one embedded within the structure of ritual); as asteroids are pieces of an exploded planet. Horror has many of the same elements featured within the ritual story such as “symbolic death” that ritual has, including pain, torture, murder and evil beings. However, a horror story abandons its characters and audience, as its “curtains fall,” just before the upward curve, while a ritual structure ensures rebirth and enlightenment. Horror originated from an incomplete ritual of “symbolic death-rebirth.’

Take a horror movie, find the hero – maybe a victim coming alive from paralyzing fear – give the screaming cornered prey guts and a sword, s/he will awake from victimhood, and defeat the deadly powers with panache. S/he will stop evil, fight to the death, survive and gain wisdom. You have a new adventure story.

Alternatively, take any good adventure or Journey story, stop it half-way – and it turns into horror. Take away from the hero the inner strength and determination necessary to avoid being a victim, and s/he will end up in the horror of the “dragon’s intestines.” Horror is an adventure with the hero deprived of power and courage. It is the storyline of the ritual of initiation broken in half. Thus death occurs and becomes a permanent condition; while death-rebirth will never take place, as it should in any mythic-ritual adventure story.

In horror, the antagonists, the dragons or other dark forces, “reverse” the story structure to become its evil-protagonists. (Consider the empowered vampires, who now demand every role in every story, from the lovers to the teachers of life). The focus is on the winners, whoever they are – zombies, serial killers, or the walking dead. And we accept their dominance, because they so convincingly win in the story.

These forms – adventure vs. horror – are mutually “convertible.” The question becomes where do screenwriters stand – are they trying to scare their contemporaries, or teaching them to overcome fear and grow? The writer endows his hero(ine) with courage, or takes it away. Similar elements are in place, but they are compositionally reconfigured and serve different social purposes.

Lets play devil’s advocate for a moment and suggest that perhaps horror stories are an early alert system, and their pessimism is therefore constructive. Indeed, in reality where a cheerful tone is set by Triumph of the Will, I’ll take the gloomy The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari anytime.

However, there is a “but.” First, the historically tried and tested genres of tragedy, mystery, crime drama, and recently film noir, though full of dark shadows, terrible twists and horrible events, do just this – provide an early alert – more effectively and in a balanced, reflective manner. They contain the mechanisms of revelation of the truth, dramatic resolution, the villain’s self-inflicted wounds, and unexpected endings that, as a whole, facilitate our contemplative response to the painful outcomes of the story.

Second, there is the notorious Kracauer question. In his seminal book From Caligari to Hitler, Siegfried Kracauer, German film scholar and refugee, asks the core question: whether the expressionist cinema, and Dr. Caligari in particular, was a warning to the Germans regarding the terrible things that were to come – the rise of Fascism – or did it “condition” them for submission to power? German expressionist cinema was about fear, but was it fear that leads to action or to passivity in accepting one’s fate?

For several years I taught a full-year Film History class, during the course of which the students in the filmmaking program and I had enough time to investigate the relationship between cinema and politics within world cultures. Among the topics proposed for the students’ course essays I included the Kracauer question. Many students chose to investigate it. Time and time again, individual students and I came to the same conclusion. The cinema of fear may serve a warning, but it also teaches surrender. And so does horror.

So horror may be an ineffective response to anxiety and crisis on the part of the audience. They flock to see it again and again, eagerly hoping for “death-rebirth” and catharsis; yet waiting in vain. On a social level, the troubling consequences of horror movies is that they create spellbound self-sufficient fictional worlds of masochistic pleasure, in which this horror world’s distorted meanings become the measure of all things, including reality. With one foot in this horror-world, there is no will left to fight when facing a real problem.

Horror’s “no-future” model is adverse to the exploration of possibilities. What happens with a self-organizing system when it creates an inquiry-model of the possible future? It must internalize it to act on it. And what if this model responds in a robotic voice, “There is no future, only death”? Such a powerful signal, a signal system actually, would send the “structural order” to its end; it is a “stop being” command. Stop living.

To sum up: there is no cultural need behind, nor community-building or life-asserting function featured in, horror. If there is latent content that this form structurally conveys – it is a message “Surrender! Resistance is futile.”

Lily Alexander has been teaching film, literature, media and screenwriting for fifteen years; the last ten years in New York, at NYU and CUNY. She received her masters in drama and film, and defended a dual doctorate in anthropology and comparative cultural studies, with an emphasis on narrative, in 1998. Alexander teaches her brand of courses, which uniquely combine theories of culture and storytelling with creative writing, hoping to enthuse new Tolkiens and Rowlings. Her most recent classes, at Hunter College, focus on world fairytale, folklore, myth, novel, short story, and science fiction as part of the framework of past and present storytelling practices. Alexander’s new book Fictional Worlds: Traditions in Narrative and the Age of Visual Culture was published in October 2013 (available on amazon.com). This text is also available in digital formats, as a set of Kindle books, and forthcoming as a set of iBooks for the apple platform. The four books of the digital sets are titled, Fictional Worlds I: The Symbolic Journey & The Genres System; Fictional Worlds II: Dramatic Characters & Dramatic Action; Fictional Worlds III: Tragedy & Mystery; and Fictional Worlds IV: Comedy & the Extraordinary. Her website is storytellingonscreen.com. Email: contact (at) storytellingonscreen.com. Comments and questions are welcome.