Citizen Fan: An Interview with Filmmaker Emmanuelle Wielezynski-Debats (Part One)

/Once upon a time, there was a group of french fan boys, with names like Francois, Jean-Luc, Claude, Louis and Alan, who showed up day after day at the same movie theater, sat on the front row, and watched mostly American genre films. Sometimes they wrote about they saw, engaging in intense debates in their own publications. Soon, they began to make transformative works -- films that borrowed elements from their favorite genres, paid homage to their favorite directors, repurposed clips and remixed posters and book covers from works that had inspired them. These works were transformative in another sense -- they changed world cinema. These fan boys created the French New Wave, which has been a source of pride in French national culture ever since.

I am telling this story because I want to challenge readers to think about what it means to a fan -- a creator of transformative works -- in the context of contemporary French culture. I've been pondering this question lately because of a recently released web documentary, Citizen Fan, which may just be the best documentary about fan culture that I have seen. The videos are in French (with the option of English subtitles) and they take us deep into the world of contemporary fans of everything from Castle to Harry Potter, from My Little Pony to anime, manga, and video games. Each segment focuses on a different fan, tells their story, introduces their world, and through this process, we get a glimpse into the cultural context in which they work. The site is amply illustrated with examples of fan art. All of this was created as a labor of love by a French documentary filmmaker, Emmanuelle Wielezynski-Debats.

The filmmaker had reached out to me as she was beginning her work on this film, which was originally intended to deal with French fans of the American series, Castle, but as she describes below, expanded outward and shifted its focus along the way. She had shared with me her own sense of discovery as she fell hard for Castle and from there, fell into the world of French fandom (a community, as she notes, that has strong connections with fan cultures elsewhere around the world.) When I visited Paris a few summers ago, she asked me to do an interview, which we shot in a screening room at the Pompidou Center.

What I recall most vividly about the interview was being surrounded by French fan artists and writers who had shown up to hear my perspectives and provide potential links to the vignettes in her documentary.

I was delighted to learn that this material was now available on-line and could be accessed by those of us whose French would not be strong enough to keep up with what is being said. Unlike other documentaries about fandom, which always feel the need at some point to distance themselves and often fall into various traps of exoticizing, eroticizing and otherizing fandom, this film starts from a place of total respect for the value of what fans create. There have been other documentary projects from within fandom itself, often produced on very low budgets, often with limited production skills, but this is the first one I have seen made by a self-proclaimed fan, growing out of the fan world, and made with professional competency.

I had known France had produced some of the most intense cineastes in the world, who had helped to identify and name, for example, film noir, in the post-war period and I also knew that France has one of the most intense comics culture to be found anywhere, again suggesting a people often intensely invested in its high culture and literary traditions, but also popular culture. But I also knew that it was a country which provided very little protection for fair use and transformative works. So, I had questions about how a culture built on transformative cultural production would thrive in this particular national context. At a time when many of us in fandom studies have been calling for more work in the global and transnational dimensions of fan culture, it's exciting to have access to this rich database of how fandom operates in France.

In the three part interview which follows, Wielezynski-Debats shares with us her experiences in making the film and her observations about how French fandom navigates a culture that seems especially hostile to their identities and cultural practices.

She has been nice enough to share with us some clips from the documentary, but to have the full experience, you need to visit and explore the Citizen Fan website.

You've shared with me that part of what inspired this film was your own relationship to Castle. How did those experiences change the way you thought about what it meant to be a fan and what did you want to share about those experiences with the people beyond fandom who might be watching your film?

I didn't know what a FAN was. The word was not part of my vocabulary. What happened is that I started watching Castle. I started watching it beyond reason. I was under the spell of Castle. Yet, I didn't think to use the word FAN, which is so familiar now.

The term FAN could have been at that moment, in my opinion, only related to the pop singers' groupies. Obviously, I had no idea of transformative fans.

The internet had never played a central part in my life before that fannish time. I discovered internet because of my addiction. It probably made it stronger. I was surprised by this invasion of my privacy. I knew Castle's intrusion had something to do with my 20's, when I used to see two screwball comedies per day, in Paris theaters.

There was quite a long moment where I felt weak, because of the addiction, a bit ashamed. At that moment, if I had to call myself a fan, I would have said something like "being a fan is a self introspection through the image of an imaginary character". I didn't think that might be a pattern shared by others. I had not found a way to be creative. I didn't even know that creativity was the key. When I first discovered fanfiction, it was a shock. These people dared to do by themselves what I thought had to be made by the author.

I always had a strong respect for authors. When I read a book, I like to imagine the author behind the story. But I had to admit that reading fanfiction was more than pleasant. I could tell it was healing something. I liked it. Later, I discovered there was an audience reading those fanfiction, making comments. These people were providing themselves and others with what they needed, they were entering into the storyworld and sitting at the author's table. I thought something in the society was changing and I started to admire this phenomenon.

So yes, my encounter with French fans has changed a lot of things. They claim being a fan is an identity, they gather in a community and they create things. I suspected none of this when I was on my own. When I started, I was excited with what I had just discovered. I felt very necessary to share with people beyond fandom the different steps: being a fan, being addict, sharing, creating, feeling better.

You, Henry Jenkins, said in Citizen Fan, "the fan doesn't only raise questions, he provides answers". This is something important. The answers are not only about the Canon but also about ourselves.

I had the impression there was another French society , other than the one I used to know. Another creativity. Another relation to media, therefore to culture...and especially to American culture. I wanted to share this insight through a documentary.

Tell us more about your journey in creating this project.

I was able to meet about a hundred transformative fans, thanks to two people: BlackNight, founder of the Castle French Boardhttp://castle.frenchboard.com/; and Alixe, who writes fanfiction in Harry Potter. She created www.ffnetmodedemploi.fr">a guideline in French in order to help people post upon Fanfiction.net. I think most of French fanfiction writers know this website. These two women are highly creative. They have made several websites, written fanfiction, and fanzines and they have great skills. They are leaders. These two women are also quite different. One of them lives in the rural world and is unemployed, and she is in her mid 20's; the other one made long studies, has a full time job in Paris and is in her 40's. Their networks are very different. Both impacted Citizen Fan a lot.

In January 2012, I started meeting Castlefans all around France. I traveled by train. Fans would come to the railroad station to pick me up and we would spend the day together, discussing the documentary itself, how much it was needed and also obviously sharing views about Beckett and Castle. I enjoyed the fan-"brotherhood" or fan-"sisterhood". I was for the first time feeling the warmth of the fandom.

As I met them IRL, they became the faces of what a fan is. This word went along with people. Very nice people, easy to become friends with, especially since they were welcoming me as a fan too. They were never foreigners not one second. From the first minute, we knew each others. This close relationship was always an asset for the film and remains the same now. I interrogated them about their creations. I was not filming. We were talking for hours. I took notes about how we were going to show these creations to a larger audience. In France, as in many places in the world, writing is a noble art, so fans who write would be considered. So I thought.

In November 2011, I had contacted France Televisions online services. Boris Razon, who was the head of this department, was interested in the project. I worked with Christophe Cluzel who is really fond of the fandom activities, and Emilie Flament, who had been a Buffy the Vampire Slayer fan and had written Fanfiction. However, it took almost two years to convince the rest of the staff and to have the definite "Go". We tried to have a linear version of Call me Kate! (Citizen Fan's working title) on TV. Unfortunately, France 2, the channel that airs Castle, didn't want anything about Castle fans. They didn't see this phenomenon as a legitimate subject.

The Web-doc is a new genre. I had to understand new techniques and new priorities, that were totally different from traditional documentaries. France Televisions organized several development seminars, where Sébastien François (@sebastien_fr) a French Sociologist who made his PhD on Harry Potter Fanfiction in French, Lionel Maurel (@calimaq) a whistle blower as well as an expert of our law and Natacha Guyot (@natchaguyot) a former AO3 staff, involved in vidding as well as in academic research on Video games, took part. We tried several ideas. Nineteen groupe, the web agency that put Citizen Fan online, was here from the start, including during these development seminars.

It was decided that Citizen Fan had to be ready to upload what fans would send us. It had to meet all the requirements of France Televisions' complex digital network.

When everything was settled with France Televisions, after two years work, I learnt that the CNC (French Ministry of Culture) would not fund us, at all. Half of the budget was gone. They stated that this subject was not "sound" enough. After meeting French fans, I wanted to meet some French academics working on Fandom or Folk culture, or Fanfiction. I had very few names, and received very few answers. The first ones I contacted didn't give me the names of any colleagues. There were several dead ends.

Until I met Sébastien François, who was finishing his PhD at TELECOM Paris Tech and who is now assistant researcher at Universités Paris 13 and Paris Descartes. He is a specialist of French Fanfiction. He accepted right away and helped me during all the process of making Citizen Fan.

During all that time, I had been reading your books, as well as Hellekson and Busse‘s and Michel de Certeau’s. I watched documentaries such as Remix manifesto, IRL the Bronze, Trekkers etc... It seemed to me obvious that I had to interview you. You had the kindness to accept. Your interview was the first one I conducted, but I had already met with all my characters and I knew them well. So, I questioned you with the idea that your answers might enlighten what fans would tell me, describing their life and creative process. I constructed your interview accordingly.

I had chosen 22 fans which I found were representing, the different issues in Fandom. I always kept your answers in mind, while I was interviewing them. It helped me leading the interviews. Because of the budget cut, we ended up editing in my flat, totally out of the traditional circuit of the audiovisual production in Paris.

The editing was the longest part. I had to ask 400 people, one by one, for the authorization to use their artworks. I wanted to illustrate Citizen Fan 99% with fanarts. This was my choice. Yet, I was and remain in the uncertainty, as far as French law is concerned. Do I have the right to show transformative works, in a country where transformative - even for free - is forbidden ? I kept worrying about that, all along. And no lawyer could give me any piece of advice.

Emmanuelle Wielezynski Debats was born in 1970 , she is married and mother of one. Emmanuelle grew up in Algeria, Ivory Coast and France. She was always interested in films and originally wanted to be a scenario writer. She graduated from a Business School in France and attended Film Studies, aside from an MBA program, in Montreal. In 1993, she registered in Anthropology, in Paris VII (Jussieu) with a major in Visual Anthropology. In 1995, she directed a short film, La Voie Blanche. For 12 years, Emmanuelle has worked at various film production companies, as an assistant to directors and to an editor as well. She now lives in Normandy with her husband, Michel Debats, a film director ( Oscar nominated Winged Migration). In 2007, together they launched their own production company, La Gaptière Production, focused on documentaries. (www.lagaptiere.com)

La Gaptière Production has produced 5 films, starting with School on the Move, in 2008, a feature film released in theaters, that was selected by 50 festivals around the World and won 14 awards, as anthropological documentary, in several countries such as China, Russia, as well as the US (Columbus, Ohio and in Missoula, Montana). Then came out three TV films, Femmes en campagne (about women in rural world), Une jeunesse en jachère (about being young in rural world) and Qu'allez-vous faire de vos vingt ans ? (about Jean Jaurès' s legacy). Emmanuelle has worked during 3 years on a more personal project : Citizen Fan, just released as a webdoc.

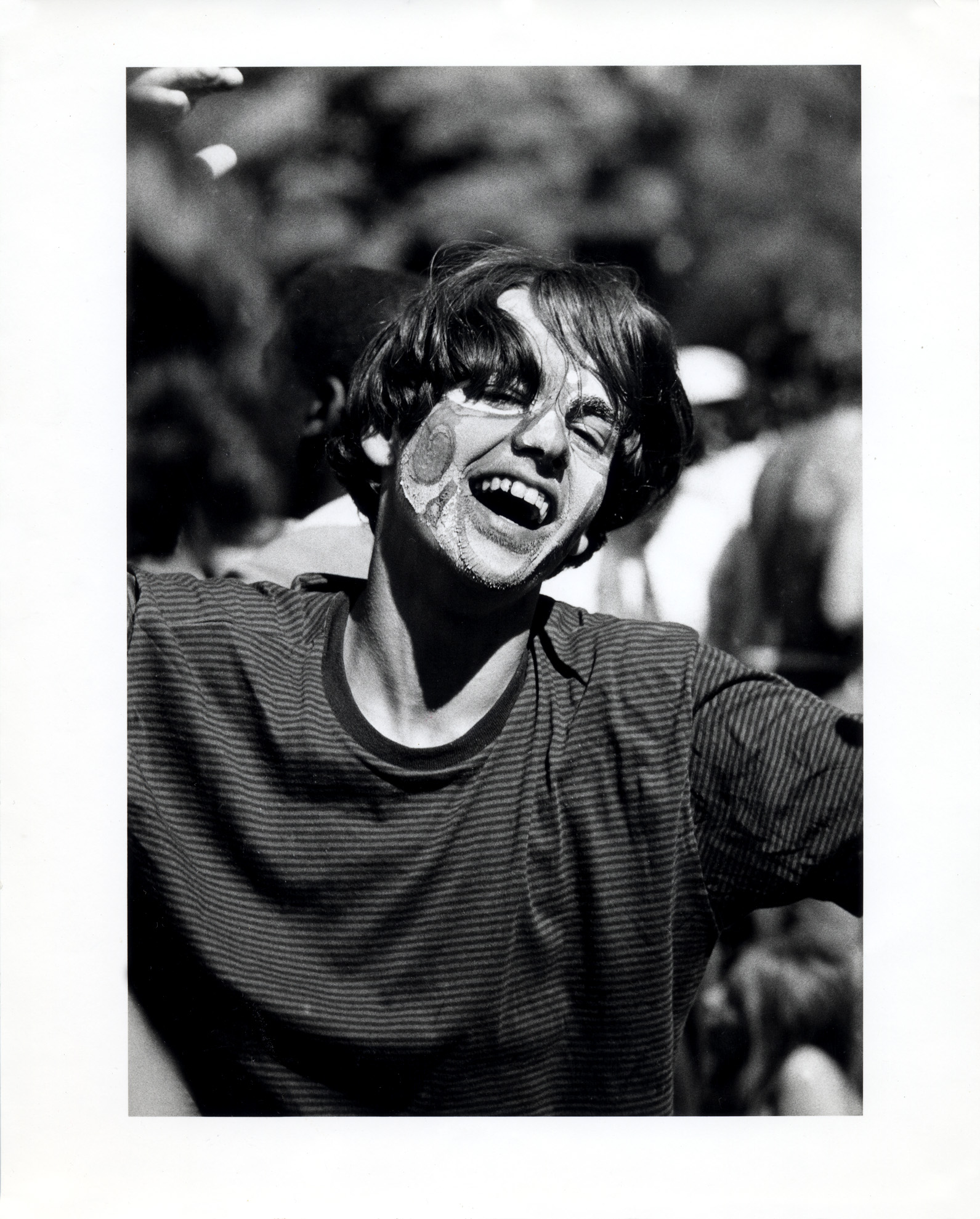

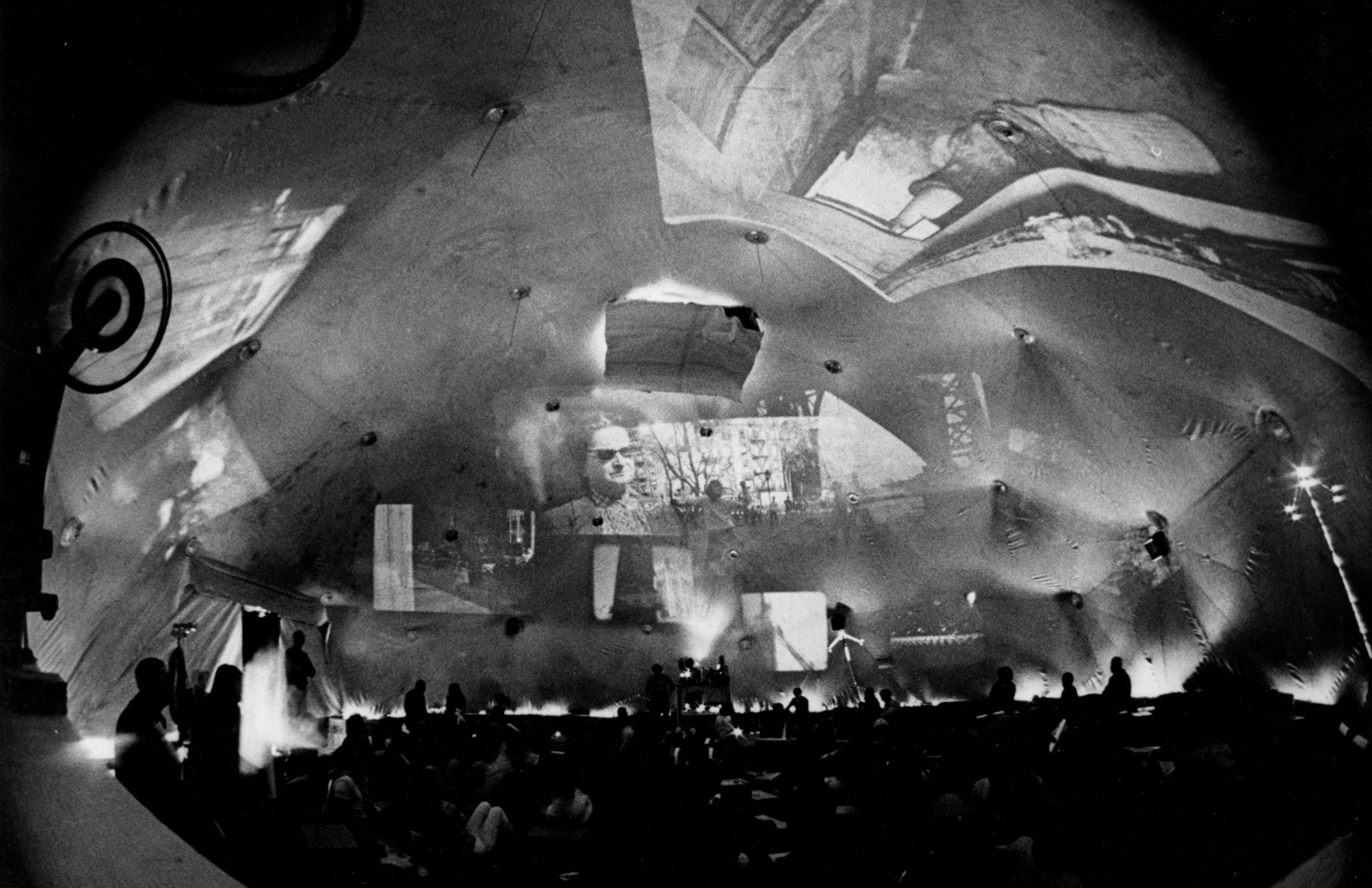

Steampunk event in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

Steampunk event in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil